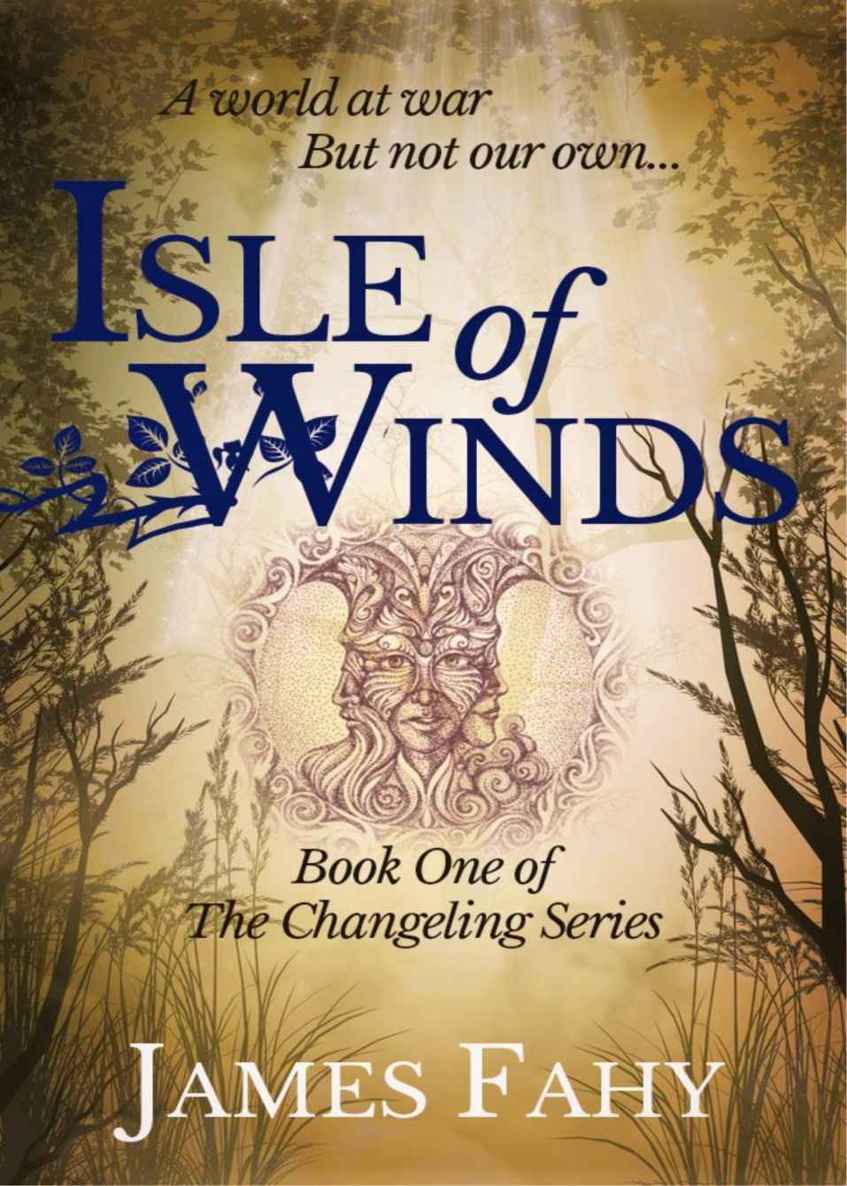

Isle of Winds (The Changeling Series Book 1)

Read Isle of Winds (The Changeling Series Book 1) Online

Authors: James Fahy

© James Fahy 2015

James Fahy has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published by Venture Press, an imprint of Endeavour Press Ltd in 2015.

The girl raced through the forest, tumbling through deep drifts of autumn leaves. Moonlight washed down from the starry sky, illuminating her darting figure.

In appearance she was eleven years old. A hunted creature. To judge from her odd clothing of ragged pants, a dirty t-shirt, and a large overcoat patched together from various animal skins, she seemed a homeless orphan. A helpless, young waif.

This, she was not.

Her breath came in gasps as she ran. Her tumbling mass of knotted brown hair snagged on branches, but her eyes were filled not with fear, only fierce determination.

They were also a rather unlikely shade of gold.

Crashes and growls in the surrounding trees told her all she needed to know about her pursuers. They were getting closer. They were much faster than her – they had more legs for a start.

Somewhere in the darkness, a hulking shadow smashed its way through bushes, throwing off clouds of leaves. Four more followed.

The running girl hardly made a sound.

She threw herself down a deep slope, skittering through scree and leaves, her keen eyes scanning the midnight shadows.

If she could make it up the other side, she would be out of the trees. Beyond the rise there was a village. They wouldn’t follow her there. They didn’t like bright lights.

She stumbled against a tree in the darkness, slapping her hands against it for support. She still had time.

There was a noise behind her.

She whirled, a flurry of animal skins and panic.

Behind her, at the top of the rise, several dark shapes stood beneath the trees. Their outlines indistinct, as though formed of shadow and smoke. She could smell the sweat in their fur, but they were not panting.

She didn’t have time after all.

A figure walked calmly from between the beasts. An old man, tall and slender. He was dressed in a rather old-fashioned suit and a long black tailcoat. His face was thin, lined and white as chalk, seeming to float in the darkness like a will o’ the wisp. His slick and oiled hair, as immaculately groomed as his clothing, was an unlikely shade of funhouse green. He showed not the slightest sign of having rushed, despite the fact that he had been pursuing her for much of the night.

“Well,” he said, his voice as crisp as the cut of his suit. He looked down the slope with cool, calm appraisal.

“Well,” the girl said in return, still leaning on the tree, trying not to pant from exhaustion.

The man laid a pale spidery hand on the head of one of the beasts. It made a long guttural growl of pleasure.

“You have led us a merry chase, haven’t you?” he called down to her.

“Wouldn’t call it merry,” the girl replied.

“You know the game is up of course, don’t you?” the man said. “I think it is probably a very brave thing you were trying to do, trying to be the first to find him.”

“You haven’t got a clue what I was trying to do,” the girl said. Her voice, strident in her mind, sounded small and annoyingly quavering. She stopped talking and settled for sticking her chin out defiantly instead.

The man on the hill was unmoved. He stared at her with cold eyes. “Oh, I think I have,” he said crisply. “I think I have many clues. And I think we both know that you would never have gotten as far as Macclesfield, the way you’ve torn through. Honestly.” He shook his head disapprovingly. “If you had the foresight to come through Janus, the proper way, you could have been much closer. You could have been on the moors by now had you come through at Todmorden. There’s a Janus Station there.”

The girl snorted. “As if you haven’t been watching the stations,” she said. “You and your skrikers would have been waiting for me.”

The shadowy creatures raised their massive heads at the sound of their name. The ghoulish man on the hill made a soothing gesture toward them.

“Down, Spitak – down, Siaw,” he said quietly.

“Enough talk, little one,” the man said. “Where is it?”

The girl smirked a little, despite the danger.

He

mustn’t

know

.

If

he

was

asking

,

he

hadn’t

guessed

.

“Where is the key?” he said sharply. “Where is the Scion? Tell me now and I may spare your life.”

“It’s not yours to spare,” the girl replied. “We both know Lady Eris is keeping you on strict orders, Mr Strife. Do you really think she’ll be happy if you bring me back in pieces?”

“My Lady Eris has not specified the conditions of your return,” Mr Strife replied, without the barest hint of a smile on his thin white lips. The cool breeze toyed with his green hair.

“Well…” said the girl. That certainly changed things. “I don’t have the key, and neither does the Scion. He doesn’t even know it exists yet, so if you kill me he’ll never know, and he’ll never find it. And you can never take it from him.”

Mr Strife’s lip curled. His teeth were very straight and white.

She tried to calculate her chances of getting up the hill behind her in one piece. If she could find a quiet spot, a place to tear through, she would be fine. She didn’t need a Janus Station. Everyone else did, but she wasn’t everyone else. The skrikers were on edge though, waiting for an excuse to pounce. She would have to try and tear through right here. Her fingers gripped the bark of the tree against which she leaned, testing it.

“He will find the key, as has been foretold. He will learn how to wield it and the Lady Eris shall have the use of it.”

“No offence,” the girl called up. “But if you were him, would

you

trust

you

?”

“Appearances are deceptive, child,” Mr Strife said quietly. “He may be relieved to find us guiding him rather than you.”

“Let’s let him decide, eh? How about that?”

Mr Strife then did something he rarely did. He smiled, like a shark in dark water.

“Oh, I think not,” he said.

With a gesture, he turned away and walked back into the trees, leaving her alone with the beasts. On cue, the skrikers descended, charging down the wooded slope. They were nothing more than muscular shadows, almost impossible to pick out in the darkness.

She stared wide-eyed for a second, and screamed a little for good effect. Or, at least, this is what she convinced herself of later. Then she tensed, and, seconds before the skrikers fell upon her, tore through.

There was a wobble in the world.

Had anyone been there to witness the moment, they would have seen something quite impossible. The girl simply sank into the tree. She fell into it as though it were murky water. The bark rippled a little, and then became solid once more, innocently challenging anyone to suggest it had ever been otherwise.

The skrikers collided with the trunk, their teeth clashing off the bole, but it was no use. The child had gone, far beyond their reach … for now.

Eventually they gave up and returned to their master, who was sitting some way off on a damp fallen log. He was looking intently at a large old-fashioned pocket watch. The dial had a large red gemstone which glittered like a droplet of blood.

They slunk up to him, as meekly as possible for a pack of large vicious beasts. One of them made a hesitant rumbling growl.

“It is done?” Mr Strife asked, his voice efficient and clean.

Another low growl.

“I see,” said Mr Strife, narrowing his eyes.

He sat quite still for a time. Then, abruptly, he snapped his pocket watch closed and stood, brushing dry leaves smartly from his coat tails.

“My Lady Eris will not be happy to hear about this,” he said calmly. He glanced at the assembled creatures. “Follow her scent,” he told them. “She cannot have gone far. Tearing is a trick indeed, but you can’t stay gone for long. She’ll turn up.”

He began to walk away, into the deeper shadows of the forest. “When she does, follow her. Let her find him. Once we know where he is, who he is, we can dispose of her and take matters into our own hands.”

Another growl, the lowest yet, issued from one of the skrikers.

“Well, try looking like ‘dogs’ then,” Mr Strife said, impatiently. “Must I think of everything? Of course it would not do to let yourselves be seen. What a question!”

There was a shiver in the forest clearing and where there had been five hellish abominations were now five large black dogs. They ran off into the trees, each in a different direction. After a few moments, when he could no longer hear them, Mr Strife sighed. One simply could not get the help these days. After all, she was just a poor girl, alone in a forest, seven miles from Macclesfield. Any number of terrible things could happen to her.

Mr Strife made a mental note to ensure that they did.

A moment later, he too was just another shadow in the dark wood.

Chapter One –

Nails and Horseshoes

It had been a very strange month for Robin. But then on reflection, he’d had a very strange life altogether.

Living with Gran had never been what could be called normal. She had some very strange habits and traditions. She liked line dancing for one, which Robin secretly felt was not a suitable pastime for a lady with a blue rinse.

She also insisted on going, every evening, around their bungalow and checking that every window and door was securely locked. Robin would be the first to admit that this in itself was not particularly unusual in little old ladies, but Gran did this three times in succession, without fail. She took care to go on her security rounds clockwise, or ‘deosil’ as she called it. Robin had looked this habit up on the internet, mildly worried that Gran may be short of a few marbles. Apparently it was called an ‘obsessive compulsive disorder’ and was reassuringly common. Quite a lot of celebrities had it.

Gran also has an astonishing array of the most inventive curses. “By the breath of the Fates!” … “Snakes and ashes!” … “Neptune’s beard!” Robin had gotten used to it over the years.

The bungalow where Robin had lived all his life with his odd Gran was normal. A nice normal bungalow in Manchester. Normal that is, except for two things. Firstly, Gran had hammered nineteen nails into the front step so that you either had to step over it altogether or suffer every morning while forgetfully fetching the milk in. Secondly, she had ensured that every doorway in the house had a horseshoe hanging over it. Every window too.

Most people simply thought that Gran collected horseshoes, in the way that old ladies collect porcelain cats, fluffy toilet roll covers, or holiday-themed tea towels. But Robin knew better. It wasn’t just above every door and every window. There were horseshoes on all the cupboard doors in the kitchen as well, on the tiny hatch for the loft in the slanted roof, above the cat flap in the back door. Pretty much everywhere in the house that led from one place to another. Some of them were large and heavy, some were small and delicate. Many of them were merely horseshoe shapes in careful silver paint. But they were everywhere.

She was perfectly normal in every other way. She liked soap operas and strange biscuits like everyone else’s Gran. She went to bingo on a Wednesday evening, and Robin went shopping with her every other week. She kept packets of crisps in the fridge, and occasionally bought cat food, though she hadn’t owned a cat since Robin was three years old.

Everyone

has

their

funny

little

ways

, Robin thought. In comparison, he himself felt boringly normal. There was nothing remotely odd about him.

His strange but familiar little life had gotten stranger in the last month. It had all started, if he wanted to put his finger on a moment in time, the night when Gran had died.

Robin had known she was dead. He had known the exact moment, even though he hadn’t been with her at the time. It had been 7:15 on a Monday evening. He had been sitting at home alone, eating spaghetti hoops on toast for tea balanced on a cushion on his lap while he watched TV. A skinny, rather pale boy with unruly blonde hair and dark blue eyes. Gran had been at a line dancing lesson at the Over Sixties Social Club two streets over, same as every Monday. He didn’t mind being left alone in the bungalow. He was twelve now after all, not a little kid anymore and their neighbour, Mr Burrows, was only next door.

Robin had known the exact second Gran had died, because at 7:15pm every horseshoe in the entire house tumbled from its mooring. They clattered down from the walls, clanking on the carpets and the linoleum in the kitchen. Spinning on the windowsills and banging against the radiators. The one which hung from the bathroom window landed in the bath, where it spun like a large coin for several seconds, making a terrible din. They fell from loose nails and bounced along the hall. Even the magnetic ones on the fridge had tumbled with a clatter to the floor, pinging off the empty cat dish.

The silver-painted, plaster-cast one Gran had brought back from a week in Cyprus, which hung above the fire in pride of place, had cracked into three and fallen down in pieces, scattering on the carpet.

Robin had sat motionless and wide-eyed, a trembling forkful of spaghetti hoops halfway to his mouth, as the brief but deafening cacophony subsided.

The bungalow had fallen utterly silent. Even the TV had muted itself, though Robin hadn’t touched the remote. It was so quiet he could hear the soft hum of the fridge. Then he had heard a faint musical jingle, like breaking icicles, at the front door.

His heart pounding, he had put aside his dinner and picked his way along the hall, stepping over the many scattered horseshoes that lay everywhere, and nervously had opened the front door.

There had been no one there. The dark street was deserted. In the distance a dog barked. He had looked down and found the source of the tinkling noise. The nails that had been driven into the front step years ago had been pulled out and each one broken in half.

Robin had stared at them for a while, unsure what to think. Then he had gone back inside and sat down, looking at the phone.

It rang after about ten minutes. He thought about not answering it, but whoever was calling was not giving up. He had eventually picked up, knowing what the police on the other end were going to tell him.

Gran had died. A sudden heart attack at the line dancing class, right in the middle of a Dolly Parton classic two-step.

* * *

In the week that followed, with so many different people rushing in and out of the bungalow, he hadn’t had much time to think about the whole business. Little old ladies, friends of Gran, cooed over him and several of them assured him and each other that ‘it was how she would have wanted to go.’

Robin had no other family. He had never known his parents. They had died when he was very young, on a safari in Africa. A glider plane had crashed and that had been that. Most of the people coming and going seemed not to know what to do with him. Their neighbour, the rangy old man called Mr Burrows, stayed at the house in the evenings, as everyone agreed a twelve year old boy, no matter how sensible and responsible, could not be alone by himself. Social Services had been to speak with him, a very kind-faced and patient woman whose name he couldn’t remember. She had reassured him that they were making investigations as to what would happen to him.

No

, he had told her,

Gran

had

never

mentioned

any

other

family

as

far

as

he

knew

.

He wondered in a dazed kind of way if he was going to go to an orphanage. He had never been alone before. There were lots of people around him all the time while this was happening, but he realised slowly, none of them were his people. He was alone in the world now.

On the day of the funeral it had rained so hard the cemetery had been waterlogged and Robin, who had fully expected to cry, instead spent most of the graveside ceremony worrying about getting mud on his trousers. He thought that would make Gran very angry if she’d seen. She’d never gone to church but had always dressed well on Sunday.

It was only afterwards, when everyone had gone and Mr Burrows had popped home, that Robin had five minutes alone to lock himself in the bathroom and pull himself together. He got through half a toilet roll, but was dry-eyed and waiting in the lounge when Mr Burrow returned.

The oddness with the horseshoes was forgotten.

* * *

A month later, Robin found himself sitting on a train, with a large suitcase in the rack above his head containing everything he owned, and a letter in his pocket from somebody he had never heard of.

The train rushed through some very pretty countryside. Robin had never really been out of the city much. The countryside, as far as he was concerned, was something that happened to other people. He sat in the softly rocking carriage, listening to the clackety-clack of the train and watching the hills and fields of Lancashire roll by.

He was on his way to a village called Barrowood, somewhere in the middle of nowhere, to meet a woman called Irene who shared his surname, and was apparently his only surviving relative.

He had never heard of her. He had never heard of Barrowood for that matter.

Every time the train pulled into a new station, he strained to see the name. There hadn’t been one called Barrowood yet.

He was so intent on finding the right station that when the door to the carriage was suddenly thrown open, he practically jumped out of his skin.

He turned wide-eyed, to see who had entered. It was a small skinny girl with a tangle of long brown hair and a very pale face. She was wearing a large tatty brown coat which was much too big for her and looked like it had been pieced together from bits of other coats. She was about his age, maybe a little younger.

Robin looked at the girl, who stood staring at him with wide and oddly triumphant eyes.

When it became apparent that she was neither going to move or speak, he thought he had better say something.

“Erm…” he began.

She blinked at the noise, as though startled by the scrawny boy’s ability to make noises as well as move.

“Erm…” he said again.

“Is this seat taken?” she asked suddenly.

“This seat?” Robin asked, nodding at the seat opposite him, which was clearly not.

“Yes. That one. The empty one there,” the girl said eagerly.

They both looked at it.

“No. I don’t think so,” Robin said eventually. “No one’s in here but me.”

The girl smiled and slammed the compartment door behind her. She peered through the glass for a second, then pulled down the shade.

Robin was a bit alarmed by this. More so when the girl leaned across him to pull the tasteless orange curtain across the window and plonked herself down opposite him in the now shadowy carriage.

He stared at her in surprise.

“Do you have any idea how much trouble I’ve had trying to find you?” she started.

“Find me?” Robin replied, deeply confused.

“Well, I knew you were in Manchester, but obviously couldn’t get anywhere near you with the wards in place, could I?” she said. “Had to hang around and wait for my chance. Not a very good idea when you’ve got skrikers on your tail, I can tell you. And then there was all that nasty business with your Grandmother and Mr Strife,” she babbled. “There’s nothing he won’t sink to, that one.” She patted his hand a little, making him flinch. “Sorry about your Gran. If we’d known what he was up to, we would have done something, but there was no one to watch you. There’s only me who could tear through, and the skrikers have been keeping me on the move. They give a new meaning to the idea of hounding someone…”

“How do you know about my Gran?” Robin interrupted. It was the only thing she had said so far that had made the slightest bit of sense. The young girl completely ignored his question.

“Of course, once the wards were down, there was a right old rush to get at you. I’m surprised Strife wasn’t there to jump in the window the minute it happened! You got out just in time, I don’t mind telling you! Old Burro can only do so much after all. I don’t think he could hold Janus for more than a month. But then no one knew where you’d gone. Off on a train with a suitcase? Who knew? I had to track you through the redcaps.” She shuddered. “And they’re never fun to deal with… And do you have any idea how difficult it is to tear through on a moving train? From a stationary point over there to a moving point over here?” She shuddered again. “Trust me, the physics involved are horrible.”

Robin held up his hands in a desperate bid to stop her babbling. “Wait,” he said. “Hold on a second…”

She stopped talking and blinked at him expectantly.

“Who are you? Did you … did you know my Gran?”

The girl seemed genuinely surprised by this. She opened and closed her mouth a few times, staring at him. He noticed that her eyes were a startling shade of gold. He had never seen anyone with eyes that colour before. Was she wearing contact lenses?

“Oh,” she said eventually, as realisation dawned. “You don’t know … who I am?”

Robin shook his head carefully.

“Your Grandmother never…” she trailed off, frowning with incredulity.

“What do you know about my Gran?” Robin asked. “Do you … I mean, did you know her?”

The girl shook her head absently. “Only by reputation,” she muttered, lost in thought. She looked up, golden eyes gleaming. “Well,” she said. “This certainly complicates things, doesn’t it?”

Robin, who was of the opinion that the conversation was already complicated enough, looked back at the agitated girl helplessly. She had sunk back in the chair. Her small form almost drowned in the tatty coat. She glowered at him moodily, as though he was being difficult on purpose.

“My name’s Robin,” he said, hoping this might help.

“I know what your name is,” the girl replied impatiently. “It’s written all over you.” She bit her lip in a thoughtful manner. “I was kind of counting on you being up to speed…”