Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (5 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

When the first proprietary brand of beef extract was launched in Europe in 1865 the price of meat was high. Refrigerated ships in which cheap surplus beef and mutton from Australia, New Zealand and the Americas could be exported to meat-hungry Europe became a reality only in the 1880s; so when Liebig’s

Extractum Carnis

, as its creator called it, appeared accompanied by claims that one pound of the extract contained the concentrated essence of 40 pounds of meat – the figure varies over the years – the impression made was deep and lasting. As the late Sir Jack Drummond put it in his great work

The Englishman’s Food

, first published in 1939, it was not then generally appreciated, even in medical circles, that clear soups were devoid of body-forming qualities. The beef tea produced by adding water to Liebig’s extract made an agreeable hot or cold drink but it couldn’t be regarded as a foodstuff in the ordinary sense. Such broths were more in the nature of nerve stimulants, the experts agreed. That thousands upon thousands of people still today persist in the belief that meat extracts provide – again in Drummond’s phrase – ‘the essential nutritive principles of meat in highly concentrated form’ is a tribute to the power of skilled and sustained advertising combined with the boundless capacity of the human race to believe what it wants to believe.

Baron Justus von Liebig, a world-famous German professor of chemistry ennobled in 1845 in recognition of his contribution to the science of nutrition, was a man of deeply serious purpose. He was well aware that the constituents of his condensed meat broth could not alone contribute to the formation of tissue, but did not on that account dismiss it as worthless. He believed that its stimulant

action on appetite could prove beneficial, and was convinced that the nitrogenous elements and the mineral salts extracted from the meats must have some nutritive value. He was not entirely mistaken. In 1944, ninety-seven years after he had published a description of his extract, it was established that certain quantities of riboflavin and nicotinic acid are present in meat extracts, and that if supplemented with other proteins such as those contained in wheaten bread, could be regarded as helpful for nutritional purposes. Not much more than that, however, and not on their own. Liebig had made a faulty deduction, oddly so for a man trained in the discipline of scientific analysis. He was basing his belief mainly on the example of that trusty old warhorse, the French peasant, who lived a healthy life on a diet consisting primarily of broth, potatoes and bread. The key component of course was the bread, and the potatoes were a help. But on a diet of thin meat broth alone, the toiling peasant wouldn’t have survived for long.

At the time of Liebig’s launch in Britain the extract’s promoters had little difficulty in gaining favourable publicity. Whatever the scientific opinion concerning its value, the product took off. Before long Florence Nightingale declared her faith in its medicinal benefits. In 1871, when Henry Stanley set out for darkest Africa in search of Livingstone, supplies of Liebig went with him. Charles Elmé Francatelli, one of the most respected chefs in Britain, gave the product his blessing. He didn’t refer to any supposed nutritional value it might have, but provided a testimonial guaranteed to appeal to cooks everywhere. ‘The very soul of Cookery is the Stockpot,’ he proclaimed solemnly, ‘and the finest Stockpot is Liebig’s Extract of Meat.’

What more could Liebig’s advertisers ask for? Francatelli, billed at the time he wrote his testimonial as ‘chef de cuisine to the late Emperor of the French’, died in 1876, three years after his ex-Imperial Majesty. Twenty years on, the Liebig Company was still quoting the great chef’s pronouncement. Bedevilled as it was by the stockpot-worship of the period, and ever keen to dodge its tyranny, the world of middle-class professional household cooks surely greeted Francatelli’s liberating licence to forget their cauldrons of simmering meat and bones and merely dip their spoons into the Liebig jar with a collective cheer.

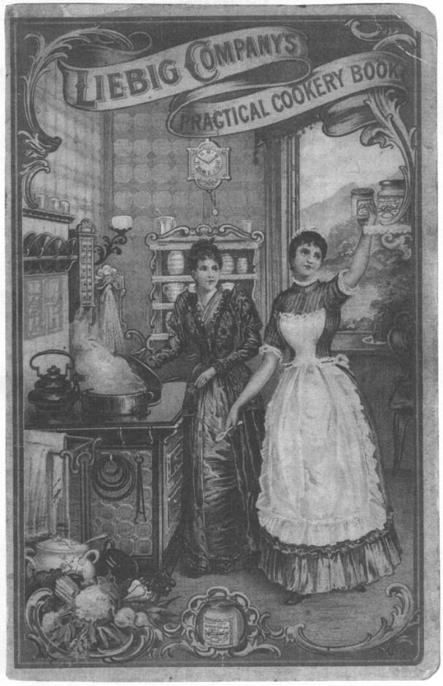

The reappearance in December 1895 of Francatelli’s magisterial dictum, prominently incorporated into a full-page advertisement for Liebig’s Extract which appeared in

The Epicure

magazine for that month, was probably not unconnected with the publication the previous year of a Liebig cookery book in which every recipe except those for sweet dishes called for the inclusion of a small amount of the extract. It was now Liebig’s policy to promote its product as an aid to middle-class domestic cookery. There was no emphasis in their little book – a pretty one, and today a collectors’ item – on the nutritional virtues of the extract; the quantities advocated in the recipes were extremely restrained, reckoned mainly in quarter and half teaspoons, and the book was sent free to all who applied for it to the company’s offices. An introduction revealed something of the scale of the Liebig operation. The vast works established on the banks of the Uruguay dealt with the processing of 1,500 head of cattle a day for seven months in the year and employed over 1,000 hands.

The publication of the Liebig cookery book was a shrewd move in what had become something of a meat extract war. As the recognised and much-bemedalled founders of a new branch of industry, the Liebig Company had attracted many imitators. Among several upstart extracts was one called Vimbos, manufactured by the Scottish Fluid Beef Company of Edinburgh. Advertisements for the product claimed a superior percentage of stimulating and flesh-forming content, plus ‘heat-producing fatty bodies and bone-forming mineral matter’. Proclaiming Vimbos the Prince of Fluid Beefs, its advertisements featured an ox squatting in a cup, its front hooves dangling forlornly over the edge. Armour & Co of Chicago produced a meat extract named Vigoral, marketed in solid concentrated form, each pound of it containing, so its producers claimed, the essence of 4 5 pounds of lean fresh beef, which made Liebig’s 40 pounds of beef to the pound of essence look rather meagre.

By the mid 1880s, Bovril was also flourishing. Bovril’s special claim was that it combined the stimulative properties of a meat extract with the nutritive constituents of meat. To achieve this end, so much desired by Baron Liebig (he had died in 1873 and was succeeded as head of the company by his son Baron H. von Liebig) the albumen and fibrine from fresh beef were desiccated, reduced to powder and added to the basic beef extract. It was beef on beef. As sustenance for polar explorers and warriors fighting Britain’s endless colonial wars, Bovril was already becoming a formidable rival to Liebig’s Extract.

Another serious competitor for Liebig’s sales was a Swiss Maggi product which was launched in the 1890s. This was a concentrated

consommé, ingeniously marketed in capsules, costing only 2d each and containing enough concentrate to make three-quarters of a pint of ‘perfect clear soup, strong and appetising’, its admirers maintained. There were also those who held that Maggi’s thirty-three varieties of French vegetable soups in tablets were equally invaluable, even indispensable.

Keeping up with its competitors in the field of advertising and publicity was one of the Liebig Company’s brilliant successes. The little cookery book was supplemented in many appealing ways with decorative souvenirs, most notably with sets of cards to be exchanged for wrappers from the jars. A seemingly inexhaustible series of brightly litho-printed cards featured an immense variety of subjects ranging from episodes in the history of ancient Rome to the contemporary seaside and its bathing machines, scenes from Shakespeare’s plays to decisive battles, popular operas, famous love stories, harlequinades. The familiar Liebig jar appeared of course on every card, and on the reverse side of each was a recipe. Wherever Liebig’s Extract was sold the cards were printed in the appropriate language – German, Italian, French, Russian, Dutch, English. Long before the advent of the cigarette card, Liebig’s pictorial cards had become collectors’ pieces.

Towards the end of the century, at a time when all other European countries fully recognised and protected Liebig’s right to the exclusive use of the name, Britain was the exception. Prior to the passing of the 1875 Trade Marks Act, unscrupulous imitators had been permitted by the British courts to appropriate the name, the design of the jars, the labels, the wrapping, of Liebig’s product. The directors of the British end of the Liebig Company at last decided that enough was enough. A drastic change of name was sought. The one they came up with – and no bad one – was Oxo. In June 1900 it was registered as a British trade mark, protected in all European countries. A new name for the new century.

For Oxo a new jar was devised, in a shape reminiscent – not entirely by coincidence, it may be supposed – of the already familiar Bovril bottle. Suggestions thrown out in the early advertising copy to the effect that a drink of Oxo was appropriate to any number of daily occasions could hardly have been more innocent. They included such non-events as before shopping and after shopping; after motoring; in foggy weather; in wet weather; when depressed; in long intervals between meals; when too busy for ordinary meals. Then came the harder sell, not exactly guileless. ‘Oxo

makes children grow into strong men and women’ was surely a reckless claim. There was also talk of ‘the energising, nourishing force of the best beef’ entering the bloodstream ‘in the shortest possible time’, references to ‘the rapid and continuous nourishment of prime lean beef’ and to ‘the highly nutritious properties of Oxo extract’. People believed the claims, and somehow, along with those made by Bovril, they entered the national consciousness.

When the first Oxo cubes – as distinct from the extract – appeared, selling them can have presented no problem at all. They were so cheap that almost anybody could afford them. Baron Liebig would have been pleased. Whether he’d have been so pleased to read the list of ingredients contained in the cubes of 1985 is a matter for conjecture. But it’s as well to mention that out of the two so-called flavour enhancers listed, 621 is the suspect MSG, and the second, 635, turns out to be a combination of substances called purines, prohibited from foods intended for young children. Gout sufferers and rheumatics generally should also avoid them. In Britain that means the great majority of the population.

Tatler

, November 1985

Taking Stock

Nearly all Englishwomen get panicky when a recipe calls for stock. Every time the word occurs in the cookery copy for a magazine or newspaper, sure as fate there’ll be a sub. on the ‘blower’ asking, can she add ‘a bouillon cube will do’? I don’t think this feeling that stock is a worrying subject is primarily a hangover from rationing. It existed, I fancy, long before the 1939 war, perhaps even before 1914. One can’t help wondering how much the cookery books of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras are to blame.

The instructions in some of these books were enough to put off the most intrepid cook. The 1891 edition of Mrs Beeton’s

Household Management

(Mrs Beeton herself had died in 1865, and the instructions are emphatically not her own) told the cook that ‘everything in the way of meat, bones, gravies and flavourings that would otherwise be wasted’ should go into the stock-pot. ‘Shank-bone of mutton, gravy left over when the half-eaten leg

was moved to another dish, trimmings of beefsteak that went into a pie, remains of gravies, bacon rinds and bones, poultry giblets, bones of roast meat, scraps of vegetables… such a pot in most houses should always be on the fire.’

Heavens, what a muddy, greasy, unattractive and quite often sour and injurious brew must have emerged from that ever-simmering tub.

There were, of course, also excellent recipes in the books for first and second stocks and broths made out of fresh ingredients, although, always with large households in mind, given in very large quantities. But somehow it was that stock-pot-cum-dustbin theory which stuck. So that gradually people have come to believe that unless they have large quantities of left-over meat and chicken carcasses, bones and scraps, it’s no use setting about making stock. It’s a good excuse too. And a shilling spent on a superior sort of bouillon cube with a continental name will, with one blow, both expunge the guilt and conceal the ignorance upon which the manufacturers and advertisers of these things are relying.

Well,

will

a bouillon cube ‘do’?

Ninety-nine times out of a hundred it will do nothing. Not, that is, if what you are hoping for is the extra stimulative value which an extract of meat is supposed to give to a soup or stew; the advantage of the extra flavour, such as it is, seems to me very doubtful.

If it is colouring you are after, then you will get it; salt, too; plus that curious prickly after-taste which appears to be characteristic of every foodstuff in which monosodium glutamate figures. All harmless enough no doubt. And as a matter of fact I think many meat-soup substitutes are more acceptable taken straight, at times when warm liquid rather than food is what one needs, than when used in cooking.

However, in the now remote days when nearly all basic ingredients were short, I used to use these cubes for soups, and other dishes which traditionally required stock. I even recommended some such product in a book. Too hastily. I soon found that every dish into which liquid made from a cube had entered had the same monotonous background flavour. (This would, of course, equally apply to pot-liquor, as the fluid from the stock-pot was called.) Pretty soon, I found, as no doubt many have found before and since, that the best way out of the difficulty was to use plain water instead of the missing stock, and to make up for the flavour