Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (17 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

Put all the spices in the coffee mill and grind them until they are in a powder. The nutmeg takes the longest, and there are moments when the coffee grinder makes a rather angry whine – which it tended to do even when used for its legitimate purpose. However, so far neither the mechanism nor the lid of the grinder (a very old and much-used Moulinex) has been affected.

The quantity makes enough to fill a little glass jar of approximately 45 g (1½ oz) capacity, and is sufficient to last about 6 months – one does not want to use the same spice so often that it becomes monotonous, nor is it advisable to make up too much of the mixture at one time. Although this particular blend is made up of spices which all retain their aromas very well, it still seems best to make it freshly from time to time.

Sprinkled on pork chops for grilling, on pork to be roasted, on lamb, on chicken for grilling, this spice gives a most delicious and subtle flavour. The small amount of trouble required for blending it is really worthwhile.

Unpublished, early 1970s

A SPICED HERB MIXTURE TO SPREAD ON BAKED GAMMON

This mixture is derived from the old recipes for the stuffing to go into a whole chine or back of bacon boiled in the Lincolnshire manner. This was a dish for harvest suppers.

I sometimes use the spice and herb mixture instead of ordinary breadcrumbs, or in place of a sugar glaze, to spread on the fat side of a piece of baked corner or middle gammon when the skin has been peeled off. A few minutes in the oven will set the mixture, and the joint will not dry out or become overcooked.

For a piece of gammon or bacon of approximately 1–1.2 kg (2½ lb) weight, a teacup of stuffing should be made up of the following ingredients: Fresh parsley, fresh or dried marjoram, fresh or dried mint, lemon thyme, chives when in season, the grated peel of one lemon and of half an orange, ¼ teaspoon of crushed coriander seeds, a scant ½ teaspoon of coarsely crushed black pepper, 2½2–3 tablespoons of dry breadcrumbs, a little melted butter.

The proportions of the fresh and dried herbs can be improvised according to fancy and depending on which are most plentiful. The fresh parsley is important, the mint gives a peculiarly English

flavour to the mixture, the lemon peel and the spicy coriander make up for such seventeenth-century flavourings as the violet and marigold leaves which in country districts were still used in the stuffings for boiled bacon until well on in the nineteenth century.

This mixture is delicious as a stuffing for fresh baked pork.

A variant of the recipe on

p. 181

of

Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen

GARAM MASALA

I have based my Garam Masala on a recipe given by Jon and Rumer Godden in

Shiva’s Pigeons

(Chatto, 1973). For English households I have reduced the quantities and also slightly altered the proportions – fewer cloves and cardamoms – as follows:

4 teaspoons coriander seeds, 2 teaspoons cumin seeds, seeds from 12–15 cardamom pods, ½ teaspoon whole cloves, 2 teaspoons white peppercorns, 5 cm (2 in) cinnamon bark, ¼ nutmeg.

Roast the coriander and cumin seeds on separate ovenproof plates in a moderately hot oven, 190°C/375°F/gas mark 5, for about 10 minutes. Put them with all the other spices into an electric coffee mill and grind them to a powder. Store in an airtight jar.

Unpublished, September 1973

Relishes of the Renaissance

‘A savoury addition to a meal; thing eaten with plainer food to add flavour; a savoury or piquant taste; the distinctive taste of anything.’ The OED provides other definitions of the term ‘relish’, none of them particularly satisfactory. To those of us old enough to remember that pre-war favourite Patum Peperium, the Gentleman’s Relish, there couldn’t be any doubt. A relish meant a highly savoury paste compounded of anchovy, pepper, plus other ingredients, unspecified and with a rather forbidding greyish aspect but packed in an attractive china pot. Come to think of it some years ago I bought a mini-size pot of that once-loved spread, produced by the Essex firm of Elsenham. ‘Original 1828 recipe’,

the label said. There was no reason to doubt it, and that dear old Gentleman’s Relish does in fact still exist. But what has become of all those good and interesting sweet-sour relishes, neither chutneys nor sauces but something between the two, both in taste and consistency? Many people used to make them at home, from summer and autumn fruits: damsons, plums, sloes, bullaces, bilberries, blackberries, mulberries, wild rose hips, crab apples, japonica berries, quinces. Have they entirely succumbed to the all-conquering tomato product of the Heinz company?

Never popular in France, relishes were once much appreciated in Italy, and are still loved in Austria and Bavaria. John Florio, in the Italian–English Dictionary which he called

A Worlde of Wordes

, compiled for the benefit of Anne of Denmark, queen of James I, and published in 1611, translated

sapore

as ‘any savour, smack, taste or relish, also any sauce to give meat a good taste’ and

saporoso

as ‘savoury, well tasted, full of savour’. The main distinction between a

sapore

and a

salsa

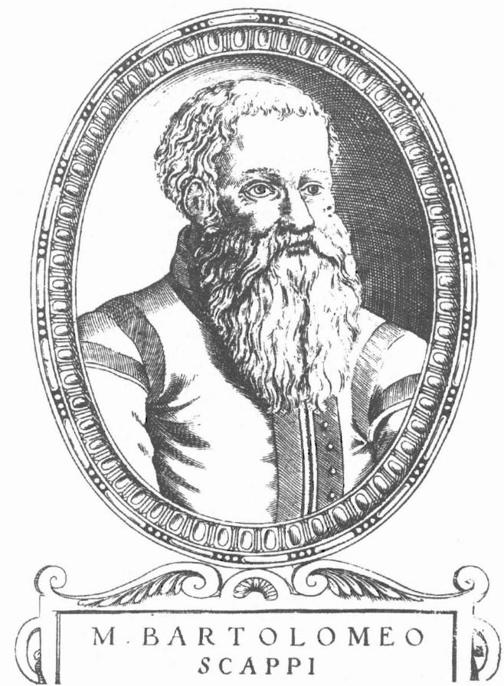

, at any rate in Bartolomeo Scappi’s great cookery book of 1570 – initially it was called simply

Opera

, later elaborated to

L’Arte del Cucinare

– seems to have been ‘keeping’ quality. A

sapore

could be stored, a

salsa

was for relatively rapid consumption. With the odd exception, a

sapore

, relish, or condiment, was very sweet and was sometimes spread over spit-roasted meat, poultry or game birds, sometimes set on the table in saucer-shaped bowls so that people could help themselves. Here are some examples from Scappi’s rich repertoire.

GALANTINA

To serve as a relish or to cover spit-roasted meat and poultry

Take one pound (500 g) of currants, pound them in a mortar with six hard boiled egg yolks, three ounces (90 g) of musk-scented biscuits (

mosiacciuoli

), three of bread toasted in the embers, steep them in rose vinegar, then temper all with six ounces (180 ml) of malmsey & four ( 12 5 ml) of clear verjuice, & pass through the sieve or strainer adding one pound (500 g) of sugar, three ounces (90 g) of sweet-sour citron juice, half an ounce (15 g) of pounded cinnamon, one ounce (30g) of pepper, & cloves & nutmeg pounded, and when it is sieved give it a warm in the saucepan, & thereafter leave it to cool, & when it is cold serve it as a relish, with sugar & cinnamon over. But if you need it to cover poultry or game birds roasted on the spit, keep it clearer with a little lean meat broth.

Notes

Verjuice, the Italian

agresto

, was one of the essential condiments of Medieval and Renaissance cookery. It was not, as often believed, simply the juice of unripe grapes, but was made from a particular acid grape cultivated especially for the purpose, and known by the same name. The vine bearing the

agresto

grape was one on which the ripe fruit and the flowers were often seen simultaneously.

Verjuice could be preserved in small vats with wine lees, covered with a cloth. When the ferment rose, the scum sank to the bottom and the juice cleared. In this manner, it was claimed, verjuice would keep a whole year, and was used as a thirst-quenching beverage as well as in cookery. Mixed with honey, it was considered beneficial in the treatment of sore throats, mouth ulcers, and scabrous eye infections.

SWEET ALMONDS

A yellow-coloured relish to serve hot or cold

In the mortar pound one pound ( 500 g) of finest skinned almonds with six ounces (180 g) of crumb of bread steeped in clear verjuice, & three ounces (90 g) of

pignoccati

(small sweetmeats shaped like pine cones), & six hard egg yolks, & when all are pounded, temper with citron juice, clear verjuice, & a little trebbiano wine, or muscat, & strain through the sieve, & put in a saucepan with a pound (500 g) of sugar, adding together pepper, cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg pounded, in all one ounce & a half (45 g), but more cinnamon than the other spicery, & cook it as the relish above – that is, with ordinary red wine and vinegar, and musk-scented biscuits – & serve hot or cold as you please, with sugar & cinnamon over.

AGLIATA

Made with fresh walnuts and almonds

Take six ounces (180 g) of fresh, shelled walnuts, & four (125 g) of fresh almonds, & six cloves of garlic parboiled, or one & a half of raw, & pound in the mortar with four ounces of crumb of bread steeped in meat or fish broth, not too salty, & when they are pounded, put thereto a quarter of an ounce (7 g) of pounded ginger. This relish if well pounded, does not need to be sieved,

but is simply tempered with one of the above broths, & if the walnuts are dry, leave them to steep in cold water until they are soft enough to skin. With this relish you may pound a little turnip, or cauliflower well cooked in meat broth, if it is a meat day.

FRESH CHERRIES WITH VERJUICE AND SPICES

Take four pounds (2 kg) of fresh Roman cherries, not too ripe, & cook them in a pot with a

foglietta

(i.e. half a Roman wine pint, about 8 oz) of clear verjuice & two ounces (60 g) of fine spice biscuits & four (125 g) of soft breadcrumbs, a little salt, one pound (500 g) of sugar, one ounce (30 g) of pepper, a quarter (7 g) of cloves, & nutmeg, & boil everything together with a

foglietta

(8 ounces/250 ml) of clear verjuice, & four ounces (125 ml) of rose vinegar, & when it is cooked press it through the sieve & this relish should have a little body, & when it is sieved, leave it to get cold, & serve it.

BLACK GRAPES

A relish for storing

Take black grapes which are firm, & they should be those called

gropello

, that is from Cesena, with the red stalks, press the grapes & put them to boil in a saucepan over a slow fire for an hour, & then take the juice which the grapes have yielded & pour it through a sieve, & for every pound (500 ml) of juice, take eight ounces (250 g) of fine sugar, & reboil it in a saucepan, skimming it, & finally add a little salt, & whole cinnamon, & let it boil over a slow fire until it starts to set, & when it is cooked, store it in glass vessels, or in glazed jars.

SWEET MUSTARD

The taste of the quince

Take one pound (500 ml) of grape juice & another of quinces cooked in wine & sugar, four ounces (125 g) of rennet apples cooked in wine, & sugar, three ounces (90 g) of candied citron peel, two ounces (60 g) of candied peel of

limoncelli

– Naples lemons, small fruit with thin skins and plenty of juice – & half an ounce (15 g) of candied nutmeg, & pound all the candied things with the quince, & with the rennet apples in the mortar, & when

all is pounded, press through the sieve together with the grape juice, & with the said ingredients three ounces (90 g) of cleaned mustard, more or less, according to whether you want it strong, & when it is sieved put thereto a little salt, & finely pounded sugar, half an ounce (15 g) of pounded cinnamon, & a quarter (7 g) of cloves pounded, & if you have no grape juice, you may make it without, taking more quince, & rennet apples, cooked as aforesaid.

Notes

The above recipe would produce a thick sweet mostarda which must surely be the ancestor of one I bought in Venice many years ago. It was late autumn, early November as I remember, and this quince

mostarda

was to be found in just one shop near the Rialto market. I was told by the shopkeeper that only a small amount was made each year because it did not keep beyond Christmas. That Venetian

mostarda amabile

was certainly a great improvement on today’s debased commercial version of Cremona

mostarda di frutta

, and as is clear from Scappi’s recipe, the making of his own

mostarda

was very much a matter of what was in season. The candied nutmeg is about the only ingredient now entirely unfamiliar to us. In Scappi’s day, and even for three centuries afterwards, nutmegs were harvested green and brought from Malaysia in sugar syrup, packed in small barrels. They could then be candied or crystallised or they could be left as they were and cut in small pieces to add spice to many dishes.

Taste

, July 1991

Italian Fruit Mustards

The sweet mustards of Italy are survivals, I think, from the days of the Roman Empire. The great French culinary scholar, Bertrand Guégan, cites a Roman recipe for the preparation of mustard given by Palladius: ‘reduce to powder a setier and a half [a setier was the equivalent of 4 litres] of mustard seed; put to it five pounds of honey, one pound of oil from Spain and one setier of strong vinegar; when all is well beat together you may use it’.

1

These Roman mixtures of honey, mustard and vinegar were sometimes

mixed with pine kernels and almonds, and were also used as a kind of syrup in which roots such as turnips were conserved. We are already getting close to the fruit mustards of the Middle Ages, at that time known as

compostes

, and evidently familiar to Italian, French, Spanish and English cooks.