Is That a Fish in Your Ear? (6 page)

Read Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Online

Authors: David Bellos

That seems so obvious as to be not worth commenting upon. But the history of a word does not tell you much about its actual meaning. Knowing, for example, that

divorce

comes from Latin

divortium

, “watershed” or “fork in the road,” does not tell you what the word means now. Etymologies obscure essential truths about the way we use language and, among them, truths about translation. So let’s be clear: a translator “carries [something] across [some obstacle]” only because the word that is used to describe what he does meant “bear across” in an ancient language. “Carrying across” is only a metaphor, and its relation to the truth about translation needs to be established, not taken for granted. There are lots of other metaphors available in many languages, including our own, and they have just as much right to our attention as the far from solid conceit of the ferry operator or trucker who carries something from A to B.

divorce

comes from Latin

divortium

, “watershed” or “fork in the road,” does not tell you what the word means now. Etymologies obscure essential truths about the way we use language and, among them, truths about translation. So let’s be clear: a translator “carries [something] across [some obstacle]” only because the word that is used to describe what he does meant “bear across” in an ancient language. “Carrying across” is only a metaphor, and its relation to the truth about translation needs to be established, not taken for granted. There are lots of other metaphors available in many languages, including our own, and they have just as much right to our attention as the far from solid conceit of the ferry operator or trucker who carries something from A to B.

What if we used a word with a different set of historical roots? What if we had lost all trace of the history of the word? Translators would no doubt carry on translating, and the problems and paradoxes of their profession would not be altered one bit. But if we were to change the word we use to talk about translation, large parts of contemporary discourse about the phenomenon would become meaningless and void.

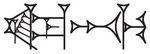

In Sumerian, the language of ancient Babylon, the word for “translator,” written in cuneiform script, looks like this:

Pronounced

eme-bal

, it means “language turner.” In classical Latin, too, what translators did was

vertere

, “to turn” (Greek) expressions into the language of Rome. We still use the same image in English when we ask a lawyer to turn the small print on a contract into something comprehensible, or when a teacher asks

a student to turn a sentence into German.

Tanimtok

, the word for “translation” in Tok Pisin, the lingua franca of Papua New Guinea, is also made of the same elements, “turn” (

tanim

) and “talk” (

tok

).

3

Of course, “turning” is almost as slippery as “carrying across,” but because you can also turn milk into butter, a frog into a prince, and base metal into gold, the history of translation (as well as the status and pay of translators) might have been significantly different in the West had the job always been thought of as a “turning.”

eme-bal

, it means “language turner.” In classical Latin, too, what translators did was

vertere

, “to turn” (Greek) expressions into the language of Rome. We still use the same image in English when we ask a lawyer to turn the small print on a contract into something comprehensible, or when a teacher asks

a student to turn a sentence into German.

Tanimtok

, the word for “translation” in Tok Pisin, the lingua franca of Papua New Guinea, is also made of the same elements, “turn” (

tanim

) and “talk” (

tok

).

3

Of course, “turning” is almost as slippery as “carrying across,” but because you can also turn milk into butter, a frog into a prince, and base metal into gold, the history of translation (as well as the status and pay of translators) might have been significantly different in the West had the job always been thought of as a “turning.”

There are two verbs in Finnish that translate

translate

: one,

kääntää

, being the same as the Finnish word for “to turn” (as in Latin); the other,

suomentaa

, meaning “to make Finnish” (just as

verdeutschen

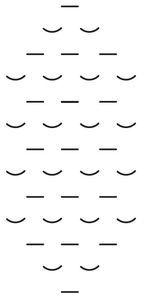

, “to make German,” is one of the German ways of saying “translate” [into German]). A witty Finnish writer took a German sight-poem by Christian Morgenstern titled “The Fish’s Lullaby” and which looks like this:

translate

: one,

kääntää

, being the same as the Finnish word for “to turn” (as in Latin); the other,

suomentaa

, meaning “to make Finnish” (just as

verdeutschen

, “to make German,” is one of the German ways of saying “translate” [into German]). A witty Finnish writer took a German sight-poem by Christian Morgenstern titled “The Fish’s Lullaby” and which looks like this:

Fisches Nachtgesang

and “turned” it into a Finnish poem that looks like this:

Kalan yölaulu

Suom. Reijo Ollinen

The joke is that the (abbreviated) word used at the bottom to state that it has been “translated by Reijo Ollinen” is not the one meaning “to turn” (over) but the one meaning “to Finnishize,” suggesting that all you need to have a fish dream in Finnish is to be turned upside down.

4

4

In ancient China, on the other hand, what you were called if you were employed as an official translator depended on which of the empire’s borders you dealt with.

Those in charge of the regions of the east were called

ji

(the entrusted; transmitters); in the south,

xiang

(likeness-renderers); in the west,

Didi

(they who know the Di tribes); and in the north,

yí

(translators/interpreters).

5

The division of a translation bureaucracy into geographical parts may sound as if it had been invented by Jorge Luis Borges, but it is not much stranger than our having separate terms such as Sinologist, Arabist, and Africanist for people working at different desks at the State Department. But it seems fairly clear from the source quoted that the use of different names for the offices held by these language people did not give rise to the view that they were each doing something different. That’s to say, before there was anything like a collective noun to describe them, the “northers,” “southers,” “easters,” and “westers” were all understood to be doing the same kind of work.

However, as Buddhism made its way into China by means of translation, the notions connected to the word

yí

expanded beyond the original definition relating to government positions dealing with the languages of the north. Here, in chronological order, spread over several centuries of classical Chinese civilization, are explanations of the character

yí

given in word lists and annotations of ancient texts:

yí

expanded beyond the original definition relating to government positions dealing with the languages of the north. Here, in chronological order, spread over several centuries of classical Chinese civilization, are explanations of the character

yí

given in word lists and annotations of ancient texts:

1.

Those who transmit the words of the tribes in the four directions.2.

To state in an orderly manner and be conversant in the words of the country and those outside the country.3.

To exchange, that is to say, to change and replace the words of one language by another to achieve mutual understanding.4.

To exchange, that is to say, to take what one has in exchange for what one does not have.

6

The point here is not to engage with ongoing debates among Sinologists about the history and meaning of the sign now pronounced

fanyí

(an augmentative form of

yí

), and which serves as the Chinese translation of

translation

, but simply this: in a culture more ancient than ours that has engaged with the practical and theoretical problems of translation with subtlety and erudition over several millennia, it occurred to no one to gloss

translation

as “the transfer of meaning from one language to another.”

fanyí

(an augmentative form of

yí

), and which serves as the Chinese translation of

translation

, but simply this: in a culture more ancient than ours that has engaged with the practical and theoretical problems of translation with subtlety and erudition over several millennia, it occurred to no one to gloss

translation

as “the transfer of meaning from one language to another.”

“Turning,” “transmitting,” “speaking after,” “mouthing,” and “exchanging” are not necessarily more revealing or more accurate ways of understanding translation. But if you inherit any of these other ways of naming acts of interlingual communication, you do not even think of defining translation as “the transfer of meaning from one language to another.” That standard English (and French, German, Russian …) definition is simply an extrapolation from the composition of the word that is used to name it. The definition tells us nothing more than the meaning of the word’s etymological roots.

The metaphor of “bearing across” has generated a wide range of words, thoughts, sayings, and banalities that may have no more reality than the idea that translation “transfers meaning” from A to B. Would we have ever thought up the idea of a “language barrier” if our word for translator did not imply something like “truck driver”? Would we have ever asked what it is that a translator “carries across” the “language barrier” if he or she were called a “turner,” “tongue man,” or “exchanger”? Probably not. The common terms of translation studies are metaphorical extensions—elaborations of the metaphor—of the etymological meaning of the term

translation

itself.

translation

itself.

But we cannot escape our own world. We do say

translate

, and we do think

transfer

, and because we think

transfer

, we have to find the complement or object of that verb. And in the mainstream tradition of Western thought about language, only one candidate has ever been thought suitable for the role:

meaning

.

translate

, and we do think

transfer

, and because we think

transfer

, we have to find the complement or object of that verb. And in the mainstream tradition of Western thought about language, only one candidate has ever been thought suitable for the role:

meaning

.

However, “meaning” is not the only component of an utterance that can in principle and in practice be “turned” into something else. Far from it. Things said are always said in some tone of voice, with some pattern of pitch, in some real context, with some kind of associated body use (gestures, posture, movement) … Written language is always presented in a particular layout, in some font or hand, in some physical medium (poster, book, back panel, or newspaper) … However, most of the dimensions that an utterance necessarily possesses are not often treated as part of the translator’s task. Like so much else, the boundaries of translation are best illuminated by a good joke.

Spanglish

is a sentimental comedy film directed by James Brooks that depicts a language situation that is no doubt familiar to many readers of this book and probably as old as the history of human society itself. The heroine is a Mexican single mother who works as a maid for a prosperous American family. She speaks no English—but her ten-year-old daughter does. At a crucial moment, the mother needs to express her thoughts and strong feelings to her employers, so she enlists her daughter to act as translator.

7

The girl is linguistically well equipped to perform the task but has no knowledge of current translation conventions. Instead of just translating the meanings of what her mother says, she replicates with gusto her mother’s theatrical body movements, in a time-lapse pas de deux. Speaking perfect English, she waves her arms, stamps her foot, and raises the volume of her voice and modulates its pitch to imitate her mother’s performance in Spanish. The sketch makes us laugh wholeheartedly. Why? Because only an intelligent but ill-educated child could imagine that’s what translation is—for us.

is a sentimental comedy film directed by James Brooks that depicts a language situation that is no doubt familiar to many readers of this book and probably as old as the history of human society itself. The heroine is a Mexican single mother who works as a maid for a prosperous American family. She speaks no English—but her ten-year-old daughter does. At a crucial moment, the mother needs to express her thoughts and strong feelings to her employers, so she enlists her daughter to act as translator.

7

The girl is linguistically well equipped to perform the task but has no knowledge of current translation conventions. Instead of just translating the meanings of what her mother says, she replicates with gusto her mother’s theatrical body movements, in a time-lapse pas de deux. Speaking perfect English, she waves her arms, stamps her foot, and raises the volume of her voice and modulates its pitch to imitate her mother’s performance in Spanish. The sketch makes us laugh wholeheartedly. Why? Because only an intelligent but ill-educated child could imagine that’s what translation is—for us.

Despite this, there are ways of reenacting in another language some of the dimensions of an utterance that don’t fall within the rather limited idea of meaning that makes translation less complex than it would otherwise be, but also much less fun. For example, take the sounds—and not the word meanings—of a familiar rhyme:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

and try to say those sounds—not their meanings—in French. Obviously, you can’t do that exactly because French uses a different set of language sounds. But we can re-say them using those French sounds that most nearly approximate the English sounds represented. We can then write them in a way that those approximately equivalent sounds would be written in French if they were the sounds of French words:

Other books

Blood Alone by James R. Benn

An End by Hughes, Paul

She Left Me Breathless by Trin Denise

Games People Play by Reed, Shelby

Arrow to the Soul by Lea Griffith

Major Crush by Jennifer Echols

Everneath by Ashton, Brodi

Dark Water Rising by Hale, Marian

Come to Castlemoor by Wilde, Jennifer;

Playing with Fire by Michele Hauf