Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (85 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

Today I assume this leadership [… ]. My people, which does not fear danger, will not forsake me, and Germany will join me in a spirit of trust. I have today taken up the old German colours and have placed myself and my people under the venerable banner of the German Reich. Prussia is henceforth merged in Germany.

47

It would be a mistake to see these extravagant gestures simply as an opportunist attempt to rally mass support around a beleaguered

monarchy. Frederick William’s enthusiasm for ‘Germany’ was entirely authentic and long predated the outbreak of the 1848 revolutions. Indeed there is something to be said for the view that he was the first truly German-minded monarch to occupy the Hohenzollern throne. Frederick William was deeply involved in the project to resume the construction of Cologne Cathedral, an imposing Gothic structure begun in 1248 but unfinished since work had ground to a halt in 1560. There had been talk of completing the cathedral since the turn of the century and Frederick William became an enthusiastic advocate and supporter of the idea. In 1842, two years after his accession, the king travelled to the Rhineland to take part in celebrations inaugurating the building works. He attended Protestant and Catholic services and presided over a cornerstone ceremony at which, to the astonishment and delight of the onlookers, he delivered a sparkling impromptu speech praising the ‘spirit of German unity and strength’ embodied in the cathedral project.

48

At around the same time, he wrote to Metternich that he had decided to devote himself to ‘ensuring the greatness, power and honour of Germany’.

49

When Frederick William spoke of German ‘unity’, he was not referring to the political unity of a nation-state, but to the diffuse, cultural, sacral unity of the medieval German Reich. His speculations did not, therefore, necessarily imply a challenge to Austria’s traditional captaincy within the community of German states. Even during the war crisis of 1840–41, when Frederick William supported efforts to extend Prussia’s influence over the security arrangements of the south German states, he was reluctant to contemplate a direct confrontation with Vienna. In the spring months of 1848, the Prussian king’s vision of the German future was still in essence a vision of the past. On 24 April, Frederick William told the Hanoverian liberal and Frankfurt deputy Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann that his vision for Germany was a kind of reinvigorated Holy Roman Empire, in which a ‘King of the Germans’ (a Prussian, perhaps) would be chosen by a revived College of Electors and wield executive power under the honorary captaincy of a Habsburg ‘Roman Emperor’.

50

As a romantic monarchical legitimist, he deplored the idea of a unilateral bid for power that would injure the historic rights of the other German crowns. He thus professed to be horrified when his new liberal foreign minister (Heinrich Alexander von Arnim-Suckow, appointed 21 March) proposed that he should accept the crown of a

new ‘German Empire’. ‘Against my own declared and well-motivated will,’ he complained to a close conservative associate, ‘[Arnim-Suckow] wants to present me!!!!!! with the imperial title… I will

not

accept the crown.’

51

Yet the king’s objection to a Prussian imperial title was by no means categorical. It would be another matter entirely if the other German princes voluntarily elected him to a position of pre-eminence and the Austrians were willing to renounce their ancient claim to leadership within the German Commonwealth. Under these circumstances, he told King Frederick August II of Saxony during the first week of May, he would be willing to consider accepting the crown of a new German Reich.

52

These were highly speculative reflections at the time, but as events unfolded over the summer and autumn of 1848, they came to seem increasingly plausible.

Within a month of the outbreak of the revolution, Prussia had an opportunity to demonstrate its willingness to show leadership in the defence of the German national interest. A crisis was brewing over the future of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, predominantly agrarian principalities that straddled the frontier between German- and Danish-speaking northern Europe. The complex legal and constitutional status of the two duchies was defined by three awkward facts: firstly, a law dating back to the fifteenth century forbade the separation of the two principalities; secondly, Holstein was a member of the German Confederation but Schleswig to the north was not; thirdly, the duchies operated under a different law of succession from that of the Kingdom of Denmark – succession through the female line was possible in the kingdom but not in the duchies, where the Salic law prevailed. The inheritance issue began to cause consternation in the early 1840s, when it became clear that the Danish crown prince, Frederick VII, was likely to die without issue. For the government in Copenhagen, the prospect loomed that Schleswig, with its numerous Danish speakers, might be separated for ever from the Danish state. In order to guard against this eventuality, Frederick’s father, Christian VIII, issued the so-called ‘Open Letter’ of 1846, in which he announced the application of Danish inheritance law to Schleswig. This would permit the Danish Crown to retain its rights in the principality through the female line, should the future king die childless. The crisis triggered in the German states by the Open Letter brought about a dramatic intensification of nationalist sentiment; as we

have seen, it also prompted many moderate liberals to look to Prussia for leadership in the face of the threat posed to the German interest (and specifically the German minority in Schleswig) by the Danish government.

Shortly after his accession to the Danish throne on 20 January 1848, Frederick VII brought the issue to a head by announcing the imminent publication of a national Danish constitution and stating that the king intended to integrate Schleswig into the Danish unitary state. A process of escalation was now under way on both sides of the border: in Copenhagen, Frederick VII’s hand was forced by the nationalist Eiderdane movement; in Berlin, Frederick William IV was pressured into responding by Arnim-Suckow, a beneficiary of the March uprising. On 21 March, the new Danish government annexed Schleswig. The Germans in the south of Schleswig responded by forming a revolutionary provisional government. Outraged by the Danish annexation, the Confederal authorities voted to make Schleswig a member of the German Confederation. Acting with the official endorsement of the German Confederation, the Prussians assembled a military contingent, reinforced by small units from several other northern German states, and marched into Schleswig on 23 April. The German troops quickly overran the Danish positions and pressed northward into Danish Jutland, though they found it impossible to break the superiority of the Danish forces at sea.

There was jubilation among the nationalists, especially in the Frankfurt Parliament, where several of the most prominent liberal deputies – including Georg Beseler, Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann and the historian Johann Gustav Droysen – had close personal connections with the duchies. What the nationalists failed adequately to appreciate was the fact that the Schleswig-Holstein question was swiftly becoming an international affair. In St Petersburg, Tsar Nicholas was furious to find his Prussian brother-in-law working, as he saw it, hand-in-hand with the revolutionary nationalists. He threatened to send in Russian troops if Prussia did not withdraw from the duchies. This energetic Russian démarche in turn aroused the disquiet of the English government, which feared that the Schleswig-Holstein question might serve as a pretext for the creation of a Russian protectorate over Denmark. Since the Danes controlled access to the Baltic Sea (the Danish straits of Sund and Kattegat were known as the ‘Bosporus of the North’), this was a matter

of great strategic concern to London. The pressure for a Prussian withdrawal began to mount. Sweden soon joined the fray, along with France, and Prussia was forced to agree to a mutual evacuation of troops under the terms of the Armistice of Malmø, signed on 26 August 1848.

53

The armistice came as a profound shock to the deputies in Frankfurt. The Prussians had signed it unilaterally, without the slightest reference to the Frankfurt Parliament. Nothing could better have demonstrated the impotence of this assembly, which was headed by a provisional ‘imperial government’, but had no armed force of its own and no means of obliging territorial governments to comply with its will. It was a serious blow to the legitimacy of the parliament, which had already begun to lose its grip on public opinion in the German states. In the initial mood of outrage that greeted the news of the armistice, a majority of the deputies voted on 5 September to block its implementation. But this was mere posturing, since the executive in Frankfurt had no means of controlling the situation in the north. On 16 September, the members voted again; this time they capitulated to power-political realities and accepted the armistice. During the riots that followed in the streets of Frankfurt, two conservative deputies were slain by an angry mob. Prussia thus demolished the hopes of the German nationalists. And yet this setback paradoxically helped to reinforce the Prussophilia of many moderate nationalist liberals, for it confirmed the centrality of Prussia to any future political resolution of the German question.

In the meanwhile, the Frankfurt Parliament was struggling to resolve the matter of the relationship between the Habsburg monarchy and the rest of Germany. Towards the end of October 1848, the deputies voted to adopt a ‘greater-German’ (

grossdeutsch

) solution to the national question: the Habsburg German (and Czech) lands would be included in the new German Reich; the non-German Habsburg lands would have to be formed into a separate constitutional entity and ruled from Vienna under a personal union. The problem was that the Austrians had no intention of accepting such an arrangement. Austria was by now recovering from the trauma of the revolution. In a vengeful crusade that took 2,000 lives, Vienna was retaken by government troops at the end of October. On 27 November, Prince Felix zu Schwarzenberg, chief minister in Vienna’s new conservative government, exploded the greater-German option by announcing that he intended the Habsburg monarchy to remain a unitary political entity. The consensus at Frankfurt now

shifted in the direction of the ‘lesser-German’ (

kleindeutsch

) solution favoured by a faction of moderate Protestant liberal nationalist deputies. Under the terms of a lesser-German option, Austria would be excluded from the new national polity, pre-eminence within which would pass (by default if not by design) to the Kingdom of Prussia.

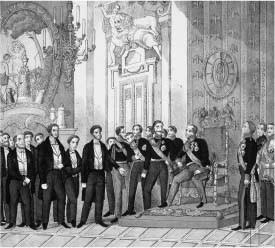

Frederick William’s speculations on a Prussian-imperial Crown were drifting from dream into reality. Late in November 1848, Heinrich von Gagern, the new minister-president (prime minister) of the provisional Reich government in Frankfurt, travelled to Berlin to attempt to persuade Frederick William to accept – in principle – a German-imperial Crown. Frederick William initially refused, observing famously that the imperial title on offer was ‘an invented crown of dirt and clay’, but he also kept open the option of an acceptance, should the Austrians and the other German princes be in agreement. The signals broadcast by the government in Berlin were sufficiently encouraging to keep the small-German option afloat for the next few months. On 27 March 1849, the Frankfurt assembly voted (by a narrow margin) to approve a monarchical constitution for the new Germany and, on the following day, a majority voted for Frederick William IV as German Emperor. In one of the famous set-pieces of German history, a delegation from the assembly, led by the Prussian liberal Eduard von Simson, travelled to Berlin to make a formal offer. The king received them on 3 April, thanked them warmly for the trust that they, in the name of the German people, had placed in his person, but refused the crown, on the grounds that Prussia could accept such an honour only on terms agreed with the other legitimate princes of the German states. In a letter addressed to his sister Charlotte – officially known as Tsarina Alexandra Federovna – but intended for the eyes of her husband, he spoke a different language: ‘You have read my reply to the man-donkey-dog-pig-and-cat delegation from Frankfurt. It means in simple German: “Sirs! You have not any right at all to offer me anything whatsoever. Ask, yes, you may ask, but give – No – for in order to give, you would first of all have to be in possession of something that can be given, and this

is not the case

!” ’

54

With Frederick William’s rejection of the crown, the fate of the great parliamentary experiment in Frankfurt was sealed. Yet the idea of a Prussian-led German union was not yet dead. During April, the Berlin government made it clear through a sequence of announcements that Frederick William IV was still willing to lead a German federal state

of some kind. On 22 April, the king’s old friend Joseph Maria von Radowitz, who had been serving as a deputy to the Frankfurt Parliament, was recalled to Berlin to coordinate policy on a German union. Radowitz aimed to disarm the objections of Vienna by proposing a system of two concentric unions. Prussia would lead a relatively cohesive ‘narrower union’, which in turn would be loosely linked to Austria through a broader union. During May 1849, there were arduous negotiations with representatives of the lesser German kingdoms, Bavaria, Württemberg, Hanover and Saxony. At the same time, it was recognized that the new entity would not succeed unless it possessed some degree of legitimacy in public opinion. To this end, Radowitz rallied liberal and conservative advocates of the small-German idea at a widely publicized meeting in the city of Gotha. Amazingly, the Austrians seemed willing to consider

the Radowitz plan; the Austrian envoy in Berlin, Count Prokesch von Osten, was much less hostile than might have been expected.