Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (52 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

portion was four times the size of Prussia’s) but it gave the Prussians more than they had traditionally aspired to and it freed Berlin from any obligation to compensate Austria in the west.

11

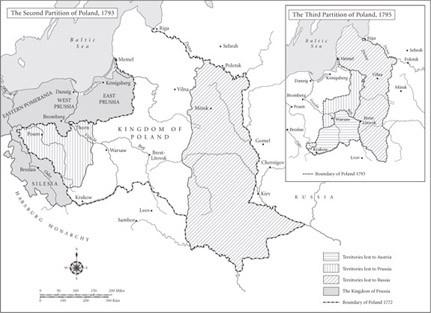

In March 1794, the uprising launched against the partition powers by the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko set the stage for a further and final partition. Although the revolt was directed primarily against Russia, it was the Prussians who first tried to take advantage of it. They hoped, by suppressing the uprising, to stake a claim for further Polish territory on an equal footing with Russia. But with substantial troop deployments still in the west, the Prussians were already seriously over-stretched; after some early successes against the revolt they were forced to pull back and call for Russian help. Seeing their chance, the Austrians, too, joined the fray. After a desperate campaign of mass recruitment, Kosciuszko held off the armies of Russia, Prussia and Austria for nearly eight months, but on 10 October 1794, a Russian victory at Maciejowice to the south-east of Warsaw brought the uprising to an end. The way was now open to the third and last partition of Poland. After bitter quarrels among the three powers, a tripartite division was agreed on 24 October 1795, by which Prussia gained a further tranche of territory encompassing about 55,000 square kilometres of land in central Poland, including the ancient capital of Warsaw, and some 1,000,000 inhabitants. Poland was no more.

Something extraordinary had happened: in the course of the second and third Polish partitions, Frederick William II, perhaps the least impressive figure to have mounted the Prussian throne over the last century and a half, secured more territory for his kingdom than any other sovereign in his dynasty’s history. Prussia grew in size by about one third to cover over 300,000 square kilometres; its population swelled from 5.5 to around 8.7 million. With its objectives in the east more than fulfilled, Prussia lost no time in extracting itself from the anti-French coalition in the west, and signing a separate peace with France at Basle on 5 April 1795.

Once again, the Prussians had left their allies in the lurch. The scribes and pamphleteers employed to produce Austrian propaganda dutifully thundered against this foul retreat from the common cause against

France. Historians have often taken a similar line, denouncing the separate peace and the neutrality that followed as contemptible, ‘cowardly’, ‘suicidal’ and ‘pernicious’.

12

The problem with such assessments is that they are founded on the anachronistic presumption that late-eighteenth-century Prussia had a German ‘national’ mission that it failed in 1795 to fulfil. But if we focus our attention firmly on the Prussian state and its interests, then the separate peace appears the best option. Prussia was financially exhausted, its domestic administration was struggling to digest vast swathes of newly acquired Polish territory and it could ill afford to continue campaigning in the west. A ‘peace party’ emerged at the Berlin court with powerful economic arguments for a withdrawal from the coalition against France.

13

The terms of the Treaty of Basle were in any case – at least on paper – highly advantageous to Prussia. Among them was an agreement by which France and Prussia undertook to uphold the neutrality of northern Germany. The neutrality zone provided Berlin with the opportunity to extend its influence over the lesser German states within the zone. Foreign Minister Haugwitz was quick to capitalize on this by persuading a string of north German territories (including Hanover) to join the Prussian neutrality system and thereby abscond from their obligations to the defence of the Holy Roman Empire.

14

Finally, the neutrality zone left Prussia’s hands free in the east and ensured that French aggression would be focused on the Austrians – to this extent it was in line with the traditional dualist policy. There was more, in other words, to neutrality than simply the avoidance of war with France. With the peace signed and Prussia safe behind the north German ‘demarcation line’, the king could afford to look upon what had been accomplished with a certain satisfaction.

His achievement was more flimsy, however, than it looked. Prussia was now isolated. Over the past six years, it had allied itself with – and then abandoned – virtually every European power. The king’s known predilection for secret diplomacy and chaotic double-dealing left him a lonely and distrusted figure on the diplomatic scene. Experience would soon show that unless Prussia could count on the assistance of a great power in defending the German demarcation line, the neutrality zone was indefensible and therefore largely meaningless. An issue of longer-term significance was the disappearance of Poland from the European map. Even if we set aside the moral outrage committed against Poland

by the partitioning powers, the fact remains that independent Poland had played a crucial role as a buffer and intermediary between the three eastern powers.

15

Now that it no longer existed, Prussia shared, for the first time in its history, a long and indefensible border with Russia.

16

From now on, the fortunes of Prussia would be inseparable from those of its vast and increasingly powerful eastern neighbour.

By taking refuge in the north German neutrality zone agreed with the French at Basle in 1795, Berlin also signalled its utter indifference to the fate of the Holy Roman Empire: the demarcation line split Germany across the middle, abandoning the south to France and the tender mercies of the Austrians. Moreover, a secret agreement appended to the Treaty of Basle in 1795 stated that if France should ultimately retain the Prussian territories she had occupied in the Rhineland, the Prussians would be compensated with territorial indemnities to the east of the Rhine – an ominous foretaste of the rush for annexations that would consume Germany at the end of the decade. The Austrians, too, abandoned any pretence of accommodating the imperial sensibilities of the lesser and least states. The Austrian forces engaged in the war with France behaved more like an army of occupation than an ally in the southern German states, and Baron Johann von Thugut, the intelligent, unscrupulous minister appointed to run Austrian foreign policy in March 1793, focused his plans for Germany around a revived version of the old Bavarian exchange project. In October 1797, Vienna concluded an agreement with Napoleon Bonaparte to trade the Austrian Netherlands for Venetia and Salzburg, one of the most prominent ecclesiastical principalities of the old Empire.

17

It seemed that the fate of Poland was about to be visited upon the Holy Roman Empire. Hans Christoph von Gagern, chief minister of the little County of Nassau, made this connection explicit when he observed in 1797: ‘The German princes have so far found themselves in the double misfortune of wishing for a rapprochement between Prussia and Austria when they think of France and of fearing one when they think of Poland.’

18

The chief objective of French policy

vis-à-vis

Germany during these years was the ‘restoration’ to France of her ‘natural frontiers’, a wholly bogus concept invented by the Assembly and fathered upon Louis XIV. In practice, this meant the wholesale annexation of the German territories along the left bank of the river Rhine. The area was a dense patchwork of imperial principalities, encompassing territories belonging

to the Hohenzollern king of Prussia, the Electorates of Cologne, Trier and Mainz, the Elector Palatine, the Duke of Pfalz-Zweibrücken, various imperial cities and numerous other lesser sovereignties. Its absorption into the French unitary state was thus bound to have a catastrophic impact on the Empire. Yet the German territories were in no position to contest France’s acquisitions in the west. The larger states – Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria – had already been forced out of the war and were looking to build bridges with France. At the Peace of Campo Formio, signed in October 1797 after Bonaparte’s victorious campaign against the Austrians in northern Italy, Vienna extended formal recognition to the French conquests in the German Rhineland. It was also agreed that the consequences of the French annexations for the Empire as a whole should be decided by direct bargaining between France and representatives of the imperial territories. The scene was thus set for the protracted negotiations that would culminate in the repartitioning of German Europe. These began in November 1797 in the picturesque Badenese city of Rastatt, and ended, after various stops and starts, with the Report of the Imperial Delegation (known in German by the gargantuan term

Reichsdeputationshauptschluss

) published in Regensburg on 27 April 1803.

The report announced a geopolitical revolution. All but six of the imperial cities were swept away; of the panoply of ecclesiastical principalities, from Cologne and Trier to the imperial abbeys of Corvey, Ellwangen and Guttenzell, only three remained on the map. The main winners were the greater and middle-sized principalities. The French, pursuing their time-honoured policy of creating German client states, were especially generous to Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria, whose geographical position between France and Austria made them useful allies. Baden was the biggest winner in proportional terms: it had lost 440 square kilometres through the French annexations but was compensated with over 3,237 square kilometres of land torn from the bishoprics of Speyer, Strassburg, Constance and Basle. Another winner was Prussia, which received the Bishopric of Hildesheim, Paderborn, the greater part of Münster, Erfurt and the Eichsfeld, the abbeys of Essen, Werden and Quedlinburg, the imperial city of Nordhausen, Mühlhausen and Goslar. Prussia had lost about 2,642 square kilometres of Rhenish lands with 127,000 inhabitants, but gained almost 13,000 square kilometres of territory with a population of around half a million.

The Holy Roman Empire was on its last legs. With the ecclesiastical principalities gone, the Catholic majorities in the diet were no more and the Catholicity of the Empire was a thing of the past. Its

raison d’e^tre

as the protective incubator for the political and constitutional diversity of traditional central Europe was exhausted. The ancient association between the imperial crown and the House of Habsburg now seemed largely meaningless, even to Leopold II’s successor, Francis II, who accordingly declared himself to be the hereditary Emperor of Austria in 1804 in order to secure an independent footing for his imperial title. The formal end of the Empire, announced by the imperial herald after the usual trumpet fanfare in Vienna on 6 August 1806, seemed a mere formality and provoked remarkably little contemporary comment.

There would be further territorial reorganizations before the Napoleonic Wars were over, but the basic outlines of a simplified nineteenth-century Germany were already visible. Prussia’s new territories reinforced its dominance in the north. The consolidation of Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria in the south created the core of a compact block of intermediary states that would confront the hegemonial ambitions of both Austria and Prussia in the post-war era. The disappearance of the ecclesiastical states also meant that millions of German Catholics now found themselves living as diasporal communities within Protestant polities, a state of affairs with far-reaching implications for the political and religious life of modern Germany. Amid the ruins of the imperial past, a German future was taking shape.

On 14 October 1806, the 26-year-old Lieutenant Johann von Borcke was posted with an army corps of 22,000 men under the command of General Ernst Wilhelm Friedrich von Rüchel to the west of the city of Jena. It was still dark when news arrived that Napoleon’s troops had engaged the main Prussian army on a plateau near the city. The noise of cannon fire could already be heard from the east. The men were cold and stiff from a night spent huddled on damp ground, but morale improved when the rising sun dispelled the fog and began to warm shoulders and limbs. ‘Hardship and hunger were forgotten,’ Borcke recalled. ‘Schiller’s

Song of the Riders

rang from a thousand throats.’

By ten o’clock, Borcke and his men were finally on the move towards Jena. As they marched eastward along the highway, they saw many walking wounded making their way back from the battlefield. ‘Everything bore the stamp of dissolution and wild flight.’ At about noon, however, an adjutant came galloping up to the column with a note from Prince Hohenlohe, commander of the main Prussian army fighting the French outside Jena: ‘Hurry, General Rüchel, to share with me the half-won victory; I am beating the French at all points.’ It was ordered that this message should be relayed down the column and a loud cheer went up from the ranks.

The approach to the battlefield took the corps through the little village of Kapellendorf; streets clogged with cannon, carriages, wounded men and dead horses slowed their progress. Emerging from the village, the corps came up on to a line of low hills, where the men had their first sight of the field of battle. To their horror, only ‘weak lines and remnants’ of Hohenlohe’s corps could still be seen resisting French attack. Moving forward to prepare for an attack, Borcke’s men found themselves in a hail of balls fired by French sharp-shooters who were so well positioned and so skilfully concealed that the shot seemed to fly in from nowhere. ‘To be shot at in this way,’ Borcke later recalled, ‘without seeing the enemy, made a dreadful impression upon our soldiers, for they were not used to that style of fighting, lost faith in their weapons and immediately sensed the enemy’s superiority.’