Iran: Empire of the Mind (9 page)

Sol Invictus

Something else taken west by the Roman soldiers from their encounters in the east was a new religion—Mithraism. Having been one of the subordinate deities of Mazdaism in the Achaemenid period, Mithras became the central god of a religion in its own right after his transition westwards—but it may be that his significance had grown in a particular context or location in Persia or Asia Minor at an earlier stage, and some have suggested that the cult was a wholly new one that took little from Persia beyond the name.

10

As worshipped in the west, Mithras always remained primarily a god of soldiers (which may point up a connection with the Parthian wars), and was an important bonding element in the lives of military men who might find themselves separated from friends and familiar places again and again in the course of their lives, as they were posted from place to place. Although Mithras was associated with the sun (the Invincible Sun—

sol invictus

), Mithraism seems to have taken on some of the ritualised cult character of western paganism, losing most of the ethical content of Iranian Mazdaism and becoming a kind of secret society a little like the Freemasons, with secret ceremonies (mysteries), initiation rites and a hierarchy of grades of membership. The underground temples of Mithras are found all over the empire, as far away from Iran as by the Walbrook in the City of London and at Carrawburgh (Roman Brocolitia) on Hadrian’s Wall. The period of the cult’s early popularity and spread was the first century

AD

.

Mithraism joins the list of important religious and intellectual influences from the Iranian lands on the West, along with the influences on Judaism and Platonism we have already considered (among others). Mithraism is thought to have had an important influence on the early Christian church,

as the Christian bishops made converts and tried to make the new religion as acceptable as possible to former pagans (though the rise of Mithraism only narrowly predates that of Christianity, and there may also have been influences in the opposite direction). To illustrate this: his followers believed that Mithras was born on 25 December, of a virgin (though some accounts say he was born from a rock), with shepherds as his first worshippers. His rites included a kind of baptism and a sacramental meal. Other aspects of the cult reflected its Mazdaean origins: Mithras was believed to have killed a bull as a sacrifice, from the blood of which all other living things emerged. Mithras was the ally of Ahura Mazda against the evil principle in the world, Ahriman.

In the following century the great soldier-Emperor Trajan managed to break the strategic logjam in the east with a new invasion of Mesopotamia, after the Parthian Vologases III had given him a pretext by deposing one ruler of Armenia and appointing another the Romans did not like. Instead of trying to toil south in the heat towards Ctesiphon under a hail of arrows on foot, in 115 (after completing the conquest of Armenia the previous year) Trajan put the men and equipment of his army into boats and ran them downstream through Mesopotamia along the river Tigris. When they reached Ctesiphon and Seleuceia they drove off the Parthian defenders and applied the most refined techniques of Roman siege engineering. The twin capital fell, and Trajan annexed the provinces of Mesopotamia to the Roman empire. He marched his men as far as the shore of the Persian Gulf, and would have liked to go further, emulating Alexander. But in 116 he fell ill while besieging Hatra, which his armies had bypassed earlier, and he died in 117.

Trajan’s conquests, although impressive enough to win him the title ‘Parthicus’ could not destroy the centres of Parthian power further east, and proved to be little more permanent than the Parthian conquests of Pacorus and Labienus in Palestine and Asia Minor of 40

BCE

. The Romans were assailed by revolts in Mesopotamia and elsewhere in their eastern provinces before Trajan died. His successor Hadrian abandoned Trajan’s conquests in Armenia and Mesopotamia and made peace with the Parthian king Osroes (Khosraw) on the basis of the old frontier on the Euphrates.

Nonetheless, Trajan had overcome the ghost of Carrhae and had shown his successors how to crack the strategic problem of Mesopotamia.

It may be that the Trajanic invasion marks the beginning of a decline of the Arsacids, and it is certainly plain that Mesopotamia had ceased to be the secure possession it had been before. Over the century that followed Roman armies penetrated to Seleuceia/Ctesiphon twice more: in 165 (under Verus), and in 199 (under Septimus Severus). But over the same period the Parthians fought back hard (assisted in 165/166 by the outbreak of a disease among the Romans that may have been smallpox), and made their own incursion into Syria (under Vologases IV in 162-166), as well as dealing with internal revolts and nomad incursions, like that of the Alans into the Caucasus in 134-136.

In 216, at the instigation of the Emperor Caracalla, the Romans again invaded, but got no further than Arbela (Irbil/Hewler). Caracalla himself, one of the most brutal of the Roman emperors (in 215 he perpetrated a massacre of many thousands of people in Alexandria because the citizens were reported to have ridiculed him), was apparently stabbed to death near Carrhae by members of his own bodyguard while he was relieving himself at the side of the road. The Parthians under Artabanus (Ardavan) IV then struck back at the Romans under Caracalla’s successor Macrinus and inflicted a heavy defeat on them at Nisibis, after which (in 218) Macrinus had to yield up a heavy war reparation of 200 million sesterces (according to Dio Cassius) to secure peace.

Whatever the precise effect of the wars on the Arsacid monarchy, they must have been exhausting and damaging, especially in Mesopotamia and the north-west, which would always have been, in good times, some of the wealthiest provinces of the empire. There had always been vicious succession disputes among the Arsacids, but these seem also to have grown more frequent and intractable, exacerbating a falling-off of the authority of the monarchy.

The Persian Revival

Early in the third century

AD

a new power began to arise in the province of Persis; Fars, the province from which the Achaemenids had emerged.

A family came to prominence as local rulers there, owing allegiance to the Arsacids. But in April 224 the latest head of this family, having broadened his support to include Kerman and Isfahan, led an army against Artabanus IV and killed him in battle at Hormuzdgan near Shushtar in Khuzestan. His name was Ardashir; a reference back to the name Artakhshathra (Artaxerxes), which had been the name of several of the Achaemenid kings. Ardashir claimed Achaemenid descent, probably to disguise the more recent, relatively humble origins of his family. The family called themselves Sassanids after a predecessor called Sasan. Ardashir also made a strong association between his cause and that of the form of Mazdaism followed in Fars (his father, Papak, had been a priest of Anahita at the religious centre of Istakhr). The downfall of Artabanus was later celebrated in a dramatic rock-carving at Ferozabad, which showed Ardashir and his followers on galloping chargers, striking the Parthian king and his men from their horses with their lances.

The Arsacid regime did not collapse immediately, and their coins were still minted in Mesopotamia until 228, but Ardashir had himself crowned

Shahanshah

(King of Kings) in 226 after taking Ctesiphon and within a few years controlled all the territory of the former Parthian empire, which fact alone suggests that several of the great Parthian families (whose local rulerships are known to have persisted long after 224) cooperated in the change of dynasty.

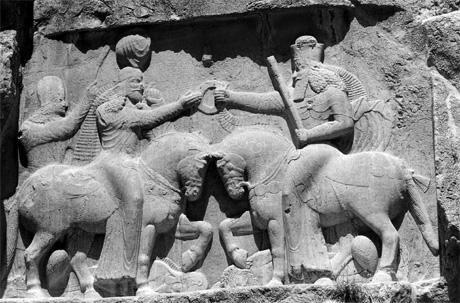

Ardashir was determined from the beginning that his new dynasty would assert and justify itself in a new way. His coins (and those of his successors) bore inscriptions in Persian script instead of the Greek used on Arsacid coins, and on the reverse showed a Mazdaean fire temple. The Sassanids were to be Iranian, Mazdaean kings before all else. In another massively impressive rock carving at Naqsh-e Rostam near Persepolis, Ardashir is shown on horseback receiving the symbol of his kingship from Ormuzd (the name of Ahura Mazda in Middle Persian). Artabanus IV is depicted crushed beneath the feet of Ardashir’s horse; Ahriman under the hooves of the horse on which Ormuzd is seated. The message could not be more clear: Ardashir had been chosen by God; his victory over the last Arsacid had been assisted by God, and he had overcome Artabanus

in a struggle that paralleled directly that of Ormuzd against Ahriman, the principle of chaos and evil

11

. Coinage inscriptions also declared Ardashir to be of ‘divine descent’—another innovation, with important later resonances. The idea may, paradoxically for this very Iranian monarch, have originated in the preceding period of Greek influence. The pattern of a new, autocratic ruler from more or less obscure origins, taking power by force after a period of disorder, and claiming the decision of God for his victory and his justification, has been suggested as a recurring theme in Iranian history by Homa Katouzian, and perhaps has its archetypal image in this relief carving.

12

The rebellion of Ardashir also, with its heavy religious overtones, echoes earlier and later religious revolutions in Iran.

Fig. 5. This massive rock carving from Naqsh-e Rostam is perhaps the definitive image of Iranian kingship. Having proved himself in war Ardashir I (left) receives the symbol of kingship from Ormuzd, founding the Sassanid dynasty.

This rock-relief also includes the first known inscription referring to Iran (though there may be references in the Avesta which probably predate the Sassanid period, and the word also appears on Ardashir’s coins). From other contemporary evidence the term Iran may refer to the territory over which those responsible for the inscriptions considered the Mazdaean religion to be observed (albeit perhaps in a variety of forms): or it may possibly

refer to the territories in which the Iranian family of languages were spoken (though the inclusion of Babylonia and Mesene within Iran makes this doubtful). Or, perhaps, it signified something less clearly defined, about people rather than territory, which partook of both things. What is more certain is that beside the concept of Iran was that of non-Iran (

Aniran

)—territories ruled by the Sassanid Shah but not regarded as Iranian—including Syria, Cilicia and Georgia.

13

Whatever the precise significance of these terms, their use strongly suggests a sense of Iranian identity, perhaps centred on Fars but with significance much beyond. It also seems unlikely that Ardashir conjured these concepts from thin air. Their utility for him was as an underpinning for his royal authority: to be effective for that purpose they must have had some resonance with his subjects that touched on an older sense of land, people and political culture.

In later years Ardashir attempted to round off his success in taking over the Parthian empire by launching attacks on the Romans on the old front in upper Mesopotamia and Syria. This suggests that he felt the need to justify his access to power by success against the Romans; and again, by extension, that the Parthians’ perceived failures against the Romans had been part of the reason for their downfall. At first impression, the interminable series of wars between the Roman empire and Persia (both in the Parthian period and again in the Sassanid period) look almost inexplicable. They went on and on, century after century. There was a potential economic gain for both sides—the disputed provinces were rich provinces. But it was evident, certainly by the time of Ardashir, that the wars were very costly, that it would be very difficult indeed for either party to deliver a knock-out blow to the other (because both had a huge hinterland behind the main theatres of war in which to recuperate) and that any gains would be difficult for either side to hold permanently. But the wars and the disputed provinces had taken on a totemic value—they had become part of the apparatus by which Persian Shahs and Roman Emperors alike justified their rule. Hence their personal participation in the campaigns. Hence the triumphs in Rome and the rock-reliefs carved on the hillsides of Fars. Upper Mesopotamia, Armenia and Syria had become an unfortunate playground for princes.

Ardashir was not especially successful initially in his wars against the Romans, but after some years was able to retake Nisibis and Carrhae. In his last years he ruled jointly with his son Shapur, who succeeded him after his death in 241. Shapur achieved some of the most dramatic successes of the long wars with Rome, beginning with his defeat of the Romans at Misikoe in 243 (killing the Roman Emperor Gordian), the submission of the Emperor Philip the Arab in 244 and the cession of Armenia. In 259/260 the Emperor Valerian, besieged by troubles including the first invasion of the Roman Empire by the Goths and an outbreak of plague as well as serious political instability, led an army against Shapur—but the Persians defeated him west of Edessa and took Valerian prisoner. These events are commemorated by another mural sculpture at Naqsh-e Rostam, which shows Shapur on horseback receiving the submission of both Roman emperors. The inscription claims that Philip paid 500,000 denarii in ransom, and that Shapur captured Valerian in battle ‘Ourselves with Our own hands.’

14

There are different accounts of what happened to Valerian thereafter. The more sensational one (from Roman sources) is that after some years of humiliation the former emperor was eventually flayed alive; his skin was then stuffed with straw and exhibited as a reminder of the superiority of Persian arms. Anthony Hecht wrote a poem based on this story, from which the following is an excerpt: