Invisible Inkling (3 page)

Authors: Emily Jenkins

D

o you want to get some pizza?” I ask gently. Pizza is the food I always want when I'm feeling alone.

“Yes, please,” says Inkling, sniffing. “What's pizza?”

“Crust and tomato sauce and cheesy goodness,” I say.

“Can you really eat it? Or is it just a symbol of something else?”

“You can really eat it,” I promise.

“Then let's go.”

He climbs onto my back. Nadia takes us to Giardini's for a small pie, since my parents have to work through dinner anyway.

At the pizza place, Inkling sits under my chair. My plan is to rip off bits and give them to him where nobody can see, the way you would a dogâbut after his first bite, Inkling starts poking my leg hard, under the table.

I poke him back.

He pokes me again. “Cheesy goodness,” he whispers. “More cheesy goodness.”

I rip him off a bigger piece and sneak it down.

It's gone in two seconds, with a small slurping noise.

“More.” He pokes me again. “More cheesy goodness.”

Nadia stands to get a shaker of oregano and some napkins. As soon as her back is turned, Inkling climbs onto the tableâI can hear him huffingâand starts pulling the rest of our pie toward him.

“Excuse me!” I grab the crust and pull it back. “You can't take the whole thing!”

Several bites disappear from one edge. I see them go invisible as they enter Inkling's mouth, a string of cheese hanging in midair before he slurps it up.

“Come on!” I say.

“Cheesy goodness,” he mumbles, between bites. “Inkling likes the cheesy goodness.”

“You're going to have to get off the table as soon as Nadia comes back,” I whisper.

“Now then!” he says. “Cheesy goodness!” The entire pie starts scooting across the table again.

“No!” I reach for it, but Inkling's too fast. The pizza flops onto the floor and zips across the tile, under two tables and several chairs, around a cooler full of drinks, and into the darkest corner of Giardini's.

In seconds, it is gone.

All that's left is the slices on our plates.

“Hank, my man,” says Nadia, returning. “Way to hog the pizza. You eat that fast, you'll make yourself sick, you know.”

“It wasn't me,” I say. “It wasâ”

She squints her eyes at me. “It was

what

? Your invisible friend?”

I start laughing, because it's true. And my life has become so strange and so happy so quickly that I can't stop. I laugh and laugh until Nadia has to hit me on the back and make me drink a glass of water.

At home that night, Inkling tells me I have to keep him secret. Over the years, humans have endangered bandapats by trapping them and locking them in hush-hush science labs. The scientists are searching for the source of bandapat invisibility, but it's never been found. And in the labs, the bandapats waste away and die from sadness. “Promise me you won't say a word, Wolowitz,” Inkling begs. “Because I can't have that happen to me. I can't be a science experiment. It would break me.”

I promise, and tell him we also have to keep him secret because of Mom's “no pets” policy. “Never, never” is the rule. She says seven hundred books, two kids, and Dad all together in our apartmentâthat's already more than she can handle.

We shake hands on it, Inkling and I. It is strange shaking hands with an invisible creature. His paw is rough on the bottom and divided into pads.

What does he look like?

Fluffy.

Stout.

Soft ears, a large tail, and padded feet with hard little claws.

That's all I can tell, so far.

Maybe he'll tell me more, later. Maybe he'll let me touch his face.

While Mom, Dad, and Nadia are on the living room couch watching

E.T

. that night, I make Inkling a bed in my laundry basket. I feed him a bowl of cereal and some leftover broccoli for dinner. “That rootbeer didn't hurt me any worse than a kangaroo I fought once,” he says, munching.

“You fought a kangaroo?”

“Oh, they're all over the outback of Ethiopia,” Inkling says. “I dropped on one that was hopping home with a huge, yummy-looking pumpkin. Waited in a tree and just dropped when the roo was least expecting it. There was big-time combat. She defended her pumpkin to the very last. But in the end, no bloodshed. Just aches and pains.”

Of course he's for-serious lyingâhello? Kangaroos don't come from Ethiopia, and last time he mentioned home it was in the Ukraineâbut it's more fun to listen to him than to call him on it.

“Who ate the pumpkin finally?” I ask.

“Me, of course. Bandapats nearly always win in combat. Invisibility gives us an advantage.”

I can't resist saying, “Except maybe with dogs, huh?”

“What?”

“Dogs, and their sense of smell. They can always tell where you are.”

“I don't know what you're talking about.”

“Rootbeer!” I say. “She can tell exactly where you are. Even when you're up in a tree.”

“The rootbeer's not a dog,” says Inkling.

“Yes, she is.”

“Listen, I have traveled all over the world, and I've seen dogs and dogs and dogs. This rootbeer is nothing like a dog. Her face is all squashed in and she has ears like a bat.”

I laugh.

“I'm fine with dogs,” Inkling claims, “but the rootbeer is another story. I have to steer clear of

her.

” He eats another piece of broccoli. “Anyway, I'm only sticking around until the Hetsnickle is paid.”

“Hetsnickle?”

“Hetsnickle was a famous bandapat. The debt of honor is named after her. You know, how I have to save your life because you saved me from that rootbeer? That's the Hetsnickle debt.”

I nod, but I'm not thinking about the Hetsnickle. What I'm really thinking is:

I have an invisible friend

.

It is not my imagination.

It is true, real life.

I have an

invisible friend.

I

n the early morning, before anyone else is up, I give Inkling a tour of the Wolowitz apartment. Dad's seven hundred books, spilling off the shelves and piled on the floor. Nadia's stash of cosmetics and hair products. The TV, the big worn sectional couch, Mom's plants, and the photograph of me and Nadia when I was just a baby, blown up larger than life and hanging in the dining area.

“You got squash in that thing?” Inkling wants to know as I show him the refrigerator.

“I doubt it.”

“Why not?”

“No one in my family likes squash.”

“You don't like squash?”

“Nah.”

“That's completely insane,” says Inkling. “I swear, I will never understand human beings.”

“You can eat breakfast cereal or bread or leftovers,” I say. “But if you eat something special like strawberries or chocolate milk, my mom might notice.” I pour some Oatie Puffs onto the kitchen counter for him and set out a dish of almonds.

“Thanks,” he says. “But see if you can get some squash in that thing. I can't stick around if there isn't going to be squash.”

“I'll try,” I tell himâbut then I don't think much more about it. Tomorrow is the first day of school. I notice Mom has put my backpack on the kitchen counter alongside a stack of folders and notebooks, plus the pencil case I picked out.

The first day of fourth grade.

Without Wainscotting.

Who will I sit with at lunch?

Who will I play with at recess?

“Do you miss your friends?” I ask Inkling. “I mean, your fellow bandapats in the Woods of Mystery or wherever?”

“Sure.”

“Do you write to them?”

“No.”

“How come? Don't bandapats write?”

“We write.”

“So why don't you write to them?”

“I don't choose to discuss it.”

“What?”

“I don't choose to discuss it.”

“Don't choose to discuss what?” I persist. “Writing?”

“I told you before, Wolowitz. Bandapats are an endangered species.”

Oh.

I feel like a jerk now. But he's said so many different things, I haven't known what to believe.

“I'm sorry,” I say.

There's no answer. Several Oatie Puffs disappear from the kitchen counter.

“Did you have a best friend?” I ask. “Someone you miss in particular?”

At first, he doesn't answer. “I was very popular,” says Inkling finally. “Let's leave it at that.”

“Come with me tomorrow,” I blurt out. “Come see what school is like.”

“What? No way.”

“You shouldn't sit lonely at home all day,” I coax. “Plus, you know all about popularity. That would be a big help to me, actually, since my best friend moved away. You could give me advice.”

“Not happening,” Inkling says.

“Why not?”

“I hate crowds. Especially crowds of children. They're dangerous for an invisible person.” Inkling makes a shivering noise. “All those feet.”

“Please?”

“If it's a matter of life and death, I'll come,” says Inkling. “Because of the Hetsnickle. Otherwise, I want to stay home and look at your pop-up books.”

“Come on, you'll like it!” I say, even though I know that isn't true.

“Is your life in danger?” Inkling demands.

“No,” I have to admit.

“Will there be squash at school?”

“No.”

“Will there be pizza?”

“Only on pizza Fridays.”

“Then this conversation is over,” Inkling says.

I hear a thump as he leaps from the kitchen counter to the floor. Then a soft

pat-pat

as he pads out of the room.

I think about following him, but I don't.

The thought of facing fourth grade alone just makes me paralyzed or something.

A

t school, the good news is that Sasha Chin from downstairs is in my class. When she sees me come into the room, she bangs a rhythm on the table where she's sitting.

Bam bam! Dada bam bam!

I'm hanging up my backpack, but I bang the same rhythm back on the wall behind my hook.

Bam bam! Dada bam bam!

It's a thing we do sometimes.

The bad news is that Locke, Linderman, and Daley are here, too. They're these girls Chin likes to hang around with. Them being in our class means that more than half the time Chin will be in girlie landâand not with me.

They're, like, her official friends.

I'm just the kid from her building she hangs out with.

Our teacher, Ms. Cherry, has complicated hair and wears very high heels. “Strangers are friends you haven't gotten to know yet,” she announces, in one of those fake teacher voices, high and jolly. “That's our motto for the start of this year. Friends are flowers in the garden of life. Let's plant an imaginary friendship flower bed together, here in our classroom!”

I don't think Ms. Cherry would understand about me and Chin being building friends but not official friends. Still, the day is going okay, for a first-ever school day without Wainscotting. We meet the new science teacher, who has a lab with frogs and giant hissing cockroaches. And we get to tell about our summer vacations.

I think my summer is going to sound boring, because all I did was hang out in Big Round Pumpkin week after week, but Linderman and Daley have lots of questions about the shop and how we make the ice cream. So I feel kinda good, knowing the answers.

Everything is really all rightâuntil gym class.

I have never been able to pay attention in gym. No matter what we're doing, my mind gets going with ideas that have nothing to do with sports. Today we're starting a soccer unit, and when the teacher is talking about halfbacks and midfielders and wingers and strikers, I think about how Nadia told me that if I went in her room again, she'd scoop my eyeballs out with a teaspoon and flush them down the toilet.

I wonder if you can really truly do that kind of eyeball scooping, or whether eyeballs are actually difficult to remove from their sockets.

If they

were

easy to get out, wouldn't eyeballs pop out by accident all the time? And sometimes you'd just see one lying on a counter in a public bathroom, or on the street, like you do candy wrappers?

That

never

happens. You never see eyeballs lying around.

So they

must

be hard to get out.

Kaminski, the gym teacher, takes us out into the big schoolyard. She divides us and kids from Mr. Hwang's class into several teams. I'm on a team called the Pink Floyds. Our opposite team is the Foo Fighters.

“Scrimmage!” Kaminski yells, and blows her whistle.

We play.

I am being a midfielder or something like that. I don't really know what's going on, but I'm trying to fake it, running in the same direction as other kids who are Pink Floyds.

Suddenly, someone yells my name. “Hank! Go!”

A ball is flying through the air.

It's coming at me.

Oh! I've got it.

I've actually got control of it.

I am going pretty fast. Down the court to the Pink Floyd goal.

A surge of joy spreads through me. I

own

that ball! People are cheering.

I kick the ball as hard as I can into the net.

Bam!

It's in!

I'm breathing hard, but it feels great, making that goal. Amazing.

Kaminski blows her whistle. She has been blowing it for quite a while, I think, and with a rush I realize: Something is wrong.

The other kids are not cheering.

They are yelling.

Mean yelling.

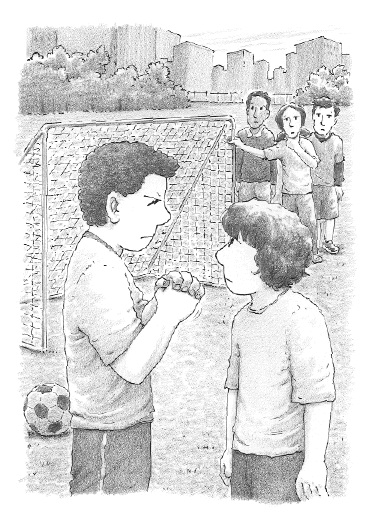

“What was that?” A big kid called Gillicut looms over me. He's in Mr. Hwang's class.

“I made a goal,” I squeak.

Gillicut points at the net. “What goal is that?” he barks.

“Pink Floyd,” I say. “I mean, I know which is my team's goal. I may not be a soccer dude, but I'm far from stupid.”

“Yeah, Spanky,” Gillicut sneers. “That

is

the Pink Floyd goal.”

“The name is Hank,” I say. “You are mispronouncing it, a little.”

“Pink Floyds put balls in the

Foo Fighter

goal,” says Gillicut. “Foo Fighters put balls in the Pink Floyd goal.”

Oh.

Drat.

“Sorry,” I say. And I really am. “But the ball did go straight in,” I add cheerfully. “Maybe our team could get partial credit?”

“There is no partial credit!” screams Gillicut. He sounds like he really, really cares about soccer. “You messed up the whole game.”

“Sorry,” I say again.

His huge Gillicut face is right on top of mine, and I'm scared he might actually murder me, he seems so mad.

Kaminski blows her whistle. “Break it up, boys. Sportsmanship, remember?”

Gillicut steps away. “Later, Spankitty Spankpants.”

“Later what?” I ask, my legs shaking.

“I. Will. See. You. Later,” he says.