Invasion Rabaul (14 page)

Authors: Bruce Gamble

F

OR HOURS THAT NIGHT,

J

OHN

L

EREW AND HIS MIXED CONVOY OF

RAAF personnel, soldiers, and civilians struggled southward along a rough and treacherous road. One truck missed a curve in the darkness and tumbled down a steep slope. No one was seriously hurt, but the remaining vehicles slowed to a crawl. The last segment of navigable roadway was little more than an overgrown track through the jungle, and it terminated at the Warangoi River. The men disabled the trucks and proceeded on foot to the riverbank, where they could see by flashlight that the muddy water was in full flood.

The only means of crossing the river was by native canoes, which had to be guided downstream and out to sea before they could be safely beached.

With only two dugouts available, the process took hours. Afterward, the rabble continued on foot through the dripping jungle and forded another river before finally reaching a large, stylish plantation called Put Put in the middle of the night.

Allowing only a brief rest, Lerew split his group into two parties. He put Flight Lieutenant Brookes in charge of the civilians, Lark Force personnel, and married men, totaling about fifty individuals. Some were beyond middle age and struggled to keep up, so Brookes commandeered two small boats to take them the rest of the way to Tol plantation. He was appalled by the behavior he witnessed that night.

“The action of certain civilians, including some senior civil servants, was disgraceful,” he later reported. “Numerous cases occurred where [men] were deliberately dumped and left behind in order that a particular person could make his escape either a little more certain or faster.”

Among those left behind were Harold Page and Harry Townsend, who decided to walk back to Rabaul with two other administration officials. Upon reaching the abandoned convoy at the Warangoi River on January 25, they made camp and waited for the Japanese to come and get them.

Meanwhile, Lerew and his party of RAAF personnel continued their journey on foot, covering another fifteen miles to Sum Sum plantation, just north of Adler Bay. They stopped to rest, and were driven under cover a few times when enemy scout planes flew over. Late that afternoon, the sound of aircraft engines sent the men scurrying under the trees once more, but someone recognized the distinctive note of Bristol Pegasus engines. The word spread quickly: there was an Empire flying boat nearby.

Actually, two of the huge four-engine seaplanes, formerly used by QANTAS for international passenger service, were searching for Lerew and his men. The radio message sent by Sergeant Higgs had been received at Port Moresby the previous day, and with no other information to go by, RAAF 20 Squadron sent aloft two Empires on a rescue attempt. However, upon learning of the imminent invasion of Rabaul, the crews elected to stop for the night at Samarai on the tip of the Papuan Peninsula. They took off again the next day, flew northward up the coast of New Britain, and were able to spot the flashlights being waved by the men at Sum Sum, just as Higgs’ message had indicated.

Two of Lerew’s men volunteered to take a boat to Tol and inform Brookes of the successful pickup, which left ninety-eight others to be ferried out to the Empires in small boats. The overloaded seaplanes failed to get airborne on their first attempts, and had to dump fuel before they were able to stagger aloft. They flew back to Samarai, where a flare path had been laid to guide them in for a hazardous night water landing. The evacuees received clean clothing and spent the night in a company store, then were airlifted the next day to Port Moresby.

Subsequently, a single Empire returned to New Britain on January 24 to pick up Brookes’ party at Wide Bay. The first forty-nine men were ferried out in a dangerously overloaded boat while Captain Denny waited on the beach with a handful of his men. The nervous loadmaster refused to delay the takeoff, however, and Denny’s small group was left behind. Gamely, they commandeered a boat and set off for the Trobriand Islands on January 27. From there, after several adventurous voyages in small boats, they reached Queensland on March 9.

Considering the lack of planning and the many variables involved, the successful

evacuation of 24 Squadron was practically a miracle. Unfortunately, as word of the airlift trickled back to Rabaul by “jungle telegraph,” hundreds of men in Lark Force were led to believe that the RAAF would return to Wide Bay and evacuate them, too. The rumors proved not only false, but resulted in an exceptionally cruel twist of fate.

CHAPTER SIX

VIGOROUS YOUTH FROM SHIKOKU

“The Japs simply walked ashore, and it was all over in one day.”

—Lieutenant Peter Figgis, NGA

Headquarters Staff

F

rom the bridge of his flagship

Okinoshima

, a 390-foot mine-laying cruiser, Rear Admiral Kiyohide Shima caught a brief glimpse of New Britain’s volcanic mountains in the distance. The weather had been steadily deteriorating as the fleet approached the island on the afternoon of January 22, and soon a line of squalls obscured his view. The reduced visibility caused anxious moments.

“As we gradually drew closer to the coastline,” Shima wrote in his diary, “we were very much worried about being taken unawares by the enemy; and indeed, it was truly by the aid of the gods that we were not troubled by them.”

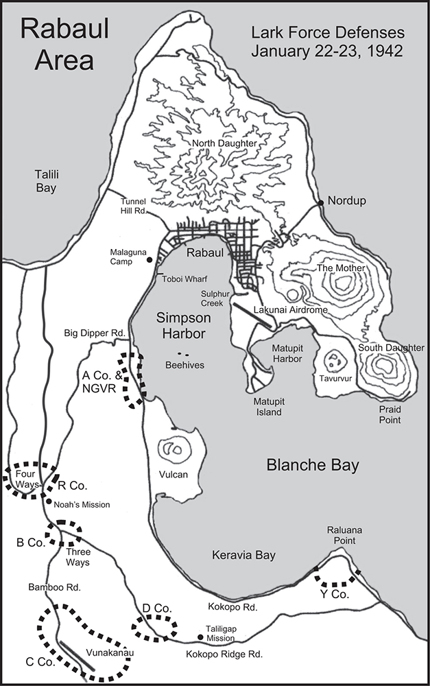

The Japanese admiral had no real cause for concern. Although his ships were being observed through long-range telescopes, the Australians could do nothing to stop him. There were no aircraft or coastal guns left to oppose the invasion fleet, and it continued unmolested down St. George’s Channel, zigzagging to kill time. By nightfall, the assembled ships were only three miles from Blanche Bay. Ahead of schedule, they held their position and waited for the signal from Major General Horii to commence landing operations.

Darkness and the poor weather favored the Japanese. The storm finally ended after midnight, leaving in its wake a low overcast that scudded over the anchorage, revealing occasional patches of starry sky. The night was moonless, perfectly suited for an invasion, and the Australians could see nothing of the fleet that had gathered offshore.

Aboard the transports, the soldiers of the South Seas Detachment were undoubtedly eager to begin the attack. They had endured nine days of unsanitary, overcrowded

conditions, and assaulting the beachhead would be a relief. While they waited, they clipped their fingernails and toenails, then placed the clippings and a lock of hair into a tiny box that would be sent home for enshrinement if they were killed. They were not overly concerned about death; if anything, they were far more worried about the possibility of dishonoring their unit, their families, or their communities.

The much-anticipated invasion began with a methodical progression of orders. First, Horii signaled the transport captains at 2030 to prepare for landing operations. An hour later, he forwarded the message, “Prepare to infiltrate to the anchorage point,” and the transports shifted to their pre-assigned launching positions. Some headed around the north shore of Crater Peninsula toward the village of Nordup, but most glided quietly into Blanche Bay.

Conditions inside the caldera were pitch black. Rabaul itself was dark except for the glow of a few fires that still burned from the morning’s air attacks; and Mount Nakamisaki, the Japanese name for Tavurvur, spewed embers bright enough to serve as a

“good landmark for reckoning directions in the darkness.” Powdery ash drifted onto the decks of the ships, adding an eerie effect to the prevailing conditions. Also, an unidentified aircraft, possibly an RAAF Catalina out of Port Moresby, released parachute flares over the harbor periodically, and their bright colors reflected off the low-hanging clouds

“with a weird beauty.”

At 2235, Horii sent the long-awaited order: “Stop and weigh anchor. Begin the landing operation.” At last, solders began clambering into dozens of Shohatsu and Daihatsu landing craft. The former, steel-hulled boats approximately forty feet long, had a capacity of about thirty troops. The more versatile Daihatsus could carry either seventy troops, twelve tons of cargo, or a medium tank.

The process of disembarking took about two hours and was completed without mishap—no small accomplishment considering the complexities of getting thousands of troops into their landing craft in pitch darkness. A strong tidal flow hindered operations and prompted the captain of at least one warship to risk turning on a searchlight to check his position.

The first group to hit the beach had the shortest distance to cover. The 1st Battalion of the 144th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Hatsuo Tsukamoto, landed near Praed Point at 0110 and quickly occupied Lakunai airdrome, accomplishing the first of

General Horii’s two main objectives. No Australians opposed the landing. Colonel Scanlan had withdrawn his forces from Crater Peninsula after the coastal guns were bombed and the runway at Lakunai was deliberately blown up. There was nothing else on the peninsula worth defending.

The Japanese were not aware of this, and one company fanned out with specific orders to capture all of the coastal gun emplacements. Faulty intelligence still estimated as many as ten

batteries on the peninsula, and the 2nd Company had until 0400 to neutralize them. If they failed, Rear Admiral Shima would have to pull the invasion fleet beyond the effective range of the guns before sunrise. The 2nd Company found the two wrecked emplacements without difficulty but continued to search frantically for “the other eight batteries.” The troops had plenty of motivation: if they did not signal their success by 0400 with a series of white star shells, the company commander was under orders to commit suicide.

I

N CONTRAST TO THE BLOODLESS OCCUPATION OF

C

RATER

P

ENINSULA, THE

Japanese encountered resistance at their other landing sites. Three companies of the 3rd Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Ishiro Kuwada, went ashore at two different positions along the rim of the caldera. They would accomplish their objective, the capture of Vunakanau airdrome, with a pincer movement. The plan called for the 8th Company to assault Raluana Point while the 7th and 9th Companies landed south of Mount Vulcan—but it didn’t work out that way. In the darkness, the coxswains steering the 9th Company’s landing craft strayed

north

of Vulcan, exactly where Major Owen’s reinforced A Company and the NGVR were waiting for them.

Concealed behind coconut log fortifications, the Australians could clearly hear the rumble of diesel motors and the scrape of steel hulls on coral. John N. Jones, a twenty-three-year-old corporal from New South Wales, was patrolling the perimeter at 0225 when he saw the barge-like landing craft approaching the beach, their silhouettes faintly backlit by the fires burning in Rabaul. The first boatload displayed remarkably poor discipline. Some of the Japanese were talking, others laughing, and one even shined a flashlight. Jones pointed a Very pistol skyward and pulled the trigger.

Seconds later, the flare cast a bright light over the beach, catching the

Japanese troops by surprise. “We allowed most of them to get out of the boats,” recalled Kenneth G. Hale, another corporal in A Company, “and then fired everything we had.”

The Australians cut loose with a withering blast. The staccato chatter of machine guns and the popping of Lee-Enfield rifles blended into a solid roar. Some of the newly delivered Thompson submachine guns added their distinctive rattle, and Captain Matheson’s antitank guns joined in with a nasty whip-

crack

. Lost among all the gunfire was the metallic thumping of mortar rounds leaving their tubes. Additional flares whooshed skyward, lighting up the beach just as the mortar shells began to land near the barbed wire. The Japanese, thrown into disarray by the explosions and concentrated firepower, twice attempted to rush the wire and twice were driven back.

The invaders withdrew into the darkness and moved laterally down the shore toward Mount Vulcan. Subsequently the Australians ceased firing, for they lacked the ammunition to blast away indiscriminately.

T

HROUGHOUT THE NIGHT, A SQUAD FROM

D C

OMPANY HAD BEEN QUIETLY

patrolling a little-used trail that led from Keravia Bay up to the plateau. An old ship’s boiler lay rusting near the beach, hence the name of the overgrown path: Boiler Road. The previous evening, the seven men had shaken hands with the rest of their platoon and bid them farewell.

“I didn’t think we’d see them again,” wrote Private Pearson in his diary, “[because] we were going out on rather a hopeless mission.”

Led by Corporal Richard V. S. Hamill, the squad was all that potentially stood between the Japanese—if they chose to land anywhere along the wide stretch of Keravia Bay—and easy access to the plateau. The Australians had a Lewis machine gun and a Tommy gun in addition to their rifles, and a light truck filled with plenty of ammunition, but no radio or field telephone. “If the Japs came up that road we were to send up a red Very light and fight a retarding action until our company came down to reinforce us,” added Pearson. It wasn’t much of a plan.