InterstellarNet: Origins (37 page)

A subvocalized command sent Gil’s chair into a smooth turn away from the plasteel wall. He silently rolled out of the visitor’s room and away from the felon’s increasingly angry shouts.

Afterword and InterstellarNet Background Material

Afterword

InterstellarNet began in musings about a far-future, star-spanning, human civilization. I presumed the pesky constraints of relativity: no FTL travel.

One thing led to another…

Soon I was pondering a comm network that functioned across the light-years. And, we homo saps being a tad competitive, about interstellar cyberwarfare.

I’m a computer guy. I started writing functional requirements for the network.

Human explorers will depart from our solar system with familiar languages, predefined protocols, and ready-made comm gear. NASA is already hard at work on an interplanetary Internet. It was more fun to imagine how an InterstellarNet might spontaneously arise—and thrive—among species that initially lack any common language, experience, or technology.

At this point, I should mention that I’m not only a computer guy. Besides computer science, there’s physics and an MBA in my shadowed past. From that MBA program comes background in economics—also known as the dismal science.

Sometimes in my fiction I play with physics. As often I play with computer science. InterstellarNet lets me play with all three sciences.

I’m hardly the first SF author to wonder how distant species might establish communications. Nor am I the first to suggest that the universality of physical laws would provide common ground. (H. Beam Piper’s “Omnilingual” did the latter way back in 1957.)

As you’ve seen, the InterstellarNet series opens with “Dangling Conversations.” Three different sciences suggested their own challenges. On the physics side: What, exactly, do math and science let us and ET say to one another? On the computer side: How, exactly, would a meaningful message be encoded between absolute strangers? On the economics side: Why would humans persist long enough to establish a dialogue with aliens light-years distant (or they with us)?

From its inception in “Dangling Conversations,” InterstellarNet was a commercial entity. Limited to primitive communications, that early commerce involved barter.

Creative Destruction

is the most famous phrase of a largely obscure economist, Joseph Schumpeter. It refers to the often brutal efficiency with which markets reallocate capital from mature technologies to emerging ones. In an example from after Schumpeter’s time, think: mainframes, then minicomputers, then PCs, and now Internet-centric applications.

I imagined we would learn to converse effectively (albeit slooowly) with our neighbors in other solar systems. They know things we don’t. They have wondrous capabilities like mature nanotechnology. To what lengths might some people go to obtain that technology, even after government bans its import because nanotech would be too disruptive or dangerous? Once everyone knows how to barter with the four-eyed, many-tentacled neighbors, who can stop the unscrupulous from violating such bans?

And so, “Creative Destruction.”

Time passes. Technologies converge as an increasingly rich trading language and the increasingly robust comm infrastructure accelerate everyone’s progress. Years-long Q&A becomes tiresome.

By “Hostile Takeover,” most InterstellarNet species have swapped trade representatives: artificially intelligent agents. This, to a computer guy, is getting really interesting. What’s to prevent us from stealing the intellectual property of aliens’ trade agents? What’s to stop us from hiding malicious software—we can all imagine things much nastier than mere viruses—in the agent software we transmit to our neighbors?

Of course whatever plots we can hatch—our neighbors can, too. Uh-oh.

As I said, I wrote functional specs. Herewith, a few of Lerner’s Laws for Artificially Intelligent Trade Agents:

1. Agents run only inside mutually agreed upon containment: the sandbox. The sandbox protects:

a. The secrets of the agent from the locals.

b. The local infosphere from the agent.

2. Sandbox code is fully disclosed and fully agreed upon across the interstellar community. (Extraterrestrial e-commerce: one more argument for open source software!)

3. Access to/from the interior of a sandbox is only by messages.

4. An agent, its software entirely proprietary to its patron species, is transmitted encrypted across interstellar space.

a. It unwraps itself inside a sandbox provided by the host species.

b. It self-destructs, its secrets undisclosed, if the behavior of the purported sandbox deviates in any way from expectations.

5. Trade wares—that is, intellectual property—travel between solar systems in encrypted form. They are unwrapped in secrecy by the sequestered AI agent. Goods are sold, or not, and bought, or not, as the agent negotiates within its authorized parameters.

6. Agents buy and sell information using the host species’s banking system. Credits not spent locally may be transmitted, securely encrypted, between solar systems.

There’s (much) more to it, of course, some of which you’ve now glimpsed in “Strange Bedfellows” and “Calculating Minds.”

Isaac Asimov’s classic robot stories revolve around loopholes and ambiguities in the Three Laws of Robotics. InterstellarNet stories likewise explore ambiguities and loopholes in interstellar commerce protocols.

InterstellarNet: New Order

(serialized as “A New Order of Things” and not part of this book) is the most ambitious InterstellarNet tale to date. The good news is interstellar travel has finally become feasible. The starships are slower than light, of course—I’m not about to make InterstellarNet obsolete.

I hope to explore InterstellarNet for a long time to come.

Edward M. Lerner

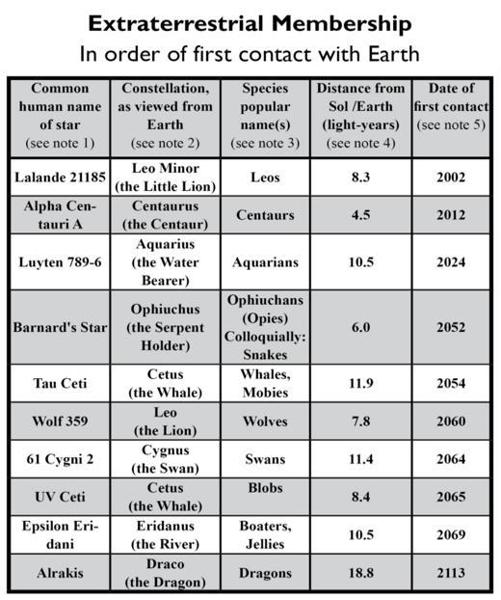

Extraterrestrial Membership in Order of First Contact with Earth

(Table may appear on next page with some font settings. See below for table notes.)

Notes to table

1. Stars far outnumber any possible set of interesting names. Most stars carry only cryptic sky-census labels, such as Lalande 21185 (even more impenetrably known in another survey as BD+362147). Still, many human-eye-visible stars, like Alpha Centauri and Alrakis, have one (or more) traditional names. Common names of a few stars, such as Barnard's Star, honor their astronomer discoverers.

2. "Constellation" suggests the general direction from Earth to the named star. Some of these stars, despite their relative proximity to Earth, are invisible to the naked eye.

3. Human nicknames for ETs often come from the constellation where their home star is found. Alien physiologies inspire other common names--for example, Jellies for the medusoid natives of Epsilon Eridani.

4. Measurements of interstellar distance vary; some researchers report slightly different values.

5. First contact: the receipt date of the first confirmed radio message from the intelligent species native to the named star.

Milestones: an Earth-centric Perspective

1958:

Leos detect Earth’s radio emissions. The faint signals are not at first recognized as evidence of intelligence.

2002:

Earth receives Leos’ radioed reply (transmitted in 1994). Humanity responds under United Nations auspices, opening an era of interstellar barter in intellectual property.

2003:

The UN begins a program of radio beamcasts to other stars, in search of other technological neighbors.

2006:

Start of the three-year-long Lalande Implosion: the collapse of petroleum-based portions of Earth’s economy. The adoption of advanced fuel-cell technology, deduced from clues within the 2002 Leo message, triggers the crash. (The fuel cells, exploiting a revolutionary new catalyst, draw power from almost any fluid hydrocarbon, including natural gas and alcohol. After 2007, few new automobiles use internal combustion.)

2010:

The “Protocol on Interstellar Technology Commerce” takes effect. The international treaty creates a new UN agency, the Interstellar Commerce Union, to oversee Earth’s radio-based commerce with extraterrestrial species.

2012:

The Centaurs contact Earth by radio, the first of many ET species to answer Earth’s exploratory messages.

2031:

A permanent lunar settlement is established. Colonies and research bases begin to spread across the solar system.

2041:

Europan gambit: an interplanetary megacorp impersonates an ET species native to Jupiter’s moon Europa, attempting to circumvent ICU refusal to import Centaur nanotechnology.

2050:

Transmissions defining Centaur nanotech reach human space, but the plot of the “Europans” is foiled.

2052:

The ICU proposes a secure e-commerce mechanism that gradually becomes the flexible basis of a more sophisticated interstellar trading community.

2055:

The United Planets Charter is ratified; the UP succeeds the United Nations.

2061:

An artificial intelligence is received from the Centaurs; the AI trade agent is successfully installed and confined by the ICU. Other AI agents follow, as more distant species receive, accept, and respond to Earth’s 2052 proposal.

2072:

The Ophiuchan AI trade agent announces a computing technology far in advance of human photonics. The debate whether to license incompletely understood alien biocomputers roils human society and interplanetary politics. The deal is not consummated until 2076.

2084:

Human and Wolf authorities acknowledge their near parity in technology, paving the way for interstellar commerce between private parties. The practice spreads as InterstellarNet fosters technological convergence.

2102:

Snake Subterfuge: the attempt, very nearly successful, to extort a fortune from humanity. The exploit involved trapdoors long hidden in the now ubiquitous—but still incompletely understood—Ophiuchan biocomputers.

2110:

The asylum request of the Centaur trade agent precipitates an artificial-intelligence emancipation movement across human space.

2112:

The AI emancipation amendment to the UP charter is ratified.

2126:

A former Secretary-General of the Interstellar Commerce Union nearly succeeds in subverting InterstellarNet trade mechanisms by illegally cloning the agent from Tau Ceti.

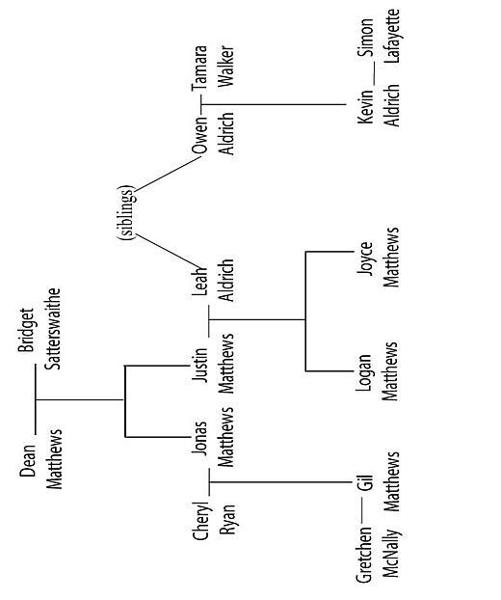

Matthews Family Tree

(Chart will appear on next page with most font settings.)