Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (31 page)

Wingate might have survived all this opposition but for increasing evidence that he was sharing sensitive information with Jewish leaders. This and the loss of his “top cover,” General Wavell, who moved on to a higher command, brought about the end of Wingate’s time in Palestine. He was sent home in 1939, his file reflecting explicitly that he should never be allowed to return there. Still, he had achieved much during his stay. As the historian Lewis Gann noted, Wingate proved in Palestine “that the counter-guerrilla, as mobile, resolute, and ubiquitous as his opponent, is worth more than the orthodox soldier when it comes to conducting anti-partisan operations.”

7

This was surely so. But Wingate’s proof of concept came at a great cost to his career. He returned home under a cloud, and prospects for further advancement seemed poor. It was the coming of World War II and the continuing support he enjoyed from General Wavell that ensured he would have new opportunities to develop his ideas further in the field.

*

Major Orde Wingate spent the opening days of World War II alternating between appeals for an amended performance evaluation and requests for a larger role for Jewish military units in the defense of the Middle East. He failed in both these pursuits. By the spring of 1940 he was slated to command an antiaircraft unit that was to deploy to Amsterdam. But the Low Countries and France fell before he could get there. That autumn, when it became clear that a German seaborne invasion of England was not in the offing—Hitler instead trying, with no success, to bomb the British into submission—Wingate was sent off to Cairo along with many other soldiers to fight the Italians. His protector, General Wavell, who was now commander-in-chief of Allied forces throughout the Middle East, had asked for him specifically.

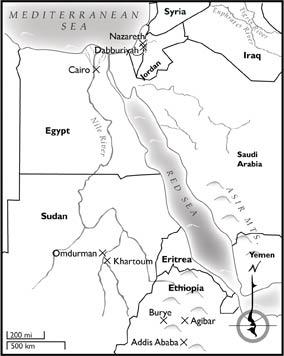

Wingate in Palestine and Ethiopia

In the days after Wingate’s arrival, Wavell was putting the finishing touches on his plan for an offensive against the Italians, who had advanced from Libya into western Egypt. The attack was to open soon, but Wavell saw no part in it for Wingate. Instead he wanted the man he considered one of Britain’s most innovative soldiers to lead an irregular campaign in support of operations to throw the Italians out of Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia), which they had invaded in 1935. At the time of the Italian incursion, the world had stood by shamefully and done nothing. Now the situation was about to change dramatically.

Haile Selassie, the “Lion of Judah” who had been driven into exile by Benito Mussolini’s forces, was ready to lead his people to freedom. Attempting to cobble together a force in Sudan, he received support from Wavell and Field Marshal Jan Smuts, the old Boer insurgent turned British loyalist. These two came to Khartoum to try to jump-start offensive preparations, but the lesser ranking British generals in this theater felt they simply had too few troops to go after the Italians.

At this point Wingate showed up in Sudan. His formal title, given by Wavell, was chief officer for rebel activities, and he got right to work. He soon managed to alienate the commanding generals of the conventional forces, but he also charmed Haile Selassie. He built from scratch what he called the Gideon Force, and by January 1941, when Wavell’s brilliant North African offensive was nearing its high tide, Wingate and Haile Selassie set forth with a few thousand men, and far more camels, to liberate Ethiopia. At the same time far larger numbers—tens of thousands—of British, Indian, and South African conventional forces were slowly beginning to move against the Italians, coming at them from north and south. The Italians skillfully defended against these thrusts, giving ground only grudgingly. On the other hand, Wingate’s small force, driving from the west toward Addis Ababa, was to pose problems that the Italians could never figure out how to counter.

In a series of actions the Gideon Force continually outmaneuvered the Italians, always taking the tactical offensive against them, even when greatly outnumbered. This was a further development, on a somewhat larger scale, of the methods Wingate had begun using in Palestine. He repeatedly divided his units so that they could strike the enemy from several directions simultaneously, most notably in a series of actions running from Burye to Mankusa in late February and early March. By April, having suffered minimal losses, Wingate’s troops had inflicted four thousand casualties on the enemy and captured fifteen thousand men and millions of rounds of ammunition.

8

All this was accomplished with virtually no air support, due in part to the fact that as Wingate’s fortunes waxed, Wavell’s were waning in the face of an offensive mounted out of Libya by an energetic German general sent there to retrieve the situation, Erwin Rommel.

Wingate seemed incapable of viewing the larger reasons for the paucity of his support, believing instead that others were intriguing against him. To some extent this was surely true of the conventional force commanders fighting in Ethiopia, whose progress was slow and difficult and who clamored even more loudly than Wingate for more resources. He could not be content in the knowledge that his theory of long-range penetration had done well in yet another field test, that he had expanded its demonstrated range of applications by showing how, beyond countering insurgents and terrorists, his small units could befuddle and defeat a much larger conventional army. Instead of reveling in such validation, all Wingate tasted were ashes.

Perhaps the most aggravating moment came when, as he readied himself and Haile Selassie to enter Addis Ababa, orders arrived early in April telling Gideon Force to stand by while a South African division took the capital. There was apparently serious concern in London that if Haile Selassie went in first there would be riotous celebrations and a mass murder of Italian captives.

9

So Smuts’s Boers went first. Haile Selassie returned to his capital three weeks later, and while he was greeted with great enthusiasm, the people remained orderly.

For Wingate there was still an endgame to play out, as some large Italian formations remained in the field. Gideon Force marched north against eight thousand enemy troops at Agibar. There Wingate divided his tiny force yet again—a key portion of it being under the command of the explorer and adventurer Wilfred Thesiger

10

—and struck at the Italians and their remaining native allies from all sides, eventually besieging them. On May 23, 1941, the entire enemy force surrendered.

11

Thesiger would go on to take some of Wingate’s ideas with him to his future service in North Africa with the Long Range Desert Group, an organization inspired by concepts of the “deep strike” mantra Wingate had been intoning for years.

Wingate, who had spent every day in the field for more than four months and had fought in almost every action of his tiny force, always against superior numbers, was by now worn out and suffering from an attack of malaria. Further, he was angry and increasingly paranoid over the many slights, real and imagined, he had been made to suffer, including being given second-rate troops at the outset of the campaign and little air support during the fighting. His assessment of his operations in Abyssinia, written after he returned to Cairo in June 1941, reflected this state of mind. It was filled with ad hominem attacks on other British leaders in the field and caused an uproar, largely due to its surly, personal tone. Yet Wavell read it with concern and interest, and let Wingate know that he hoped to launch a postmortem on the campaign that would lead to future improvements.

Wavell’s time in charge of this theater, however, had run out. His successes against the Italians in East and North Africa had been more than offset by bruising defeats in Greece and Crete, as well as by Rommel’s startling first offensive in the western desert and Wavell’s failed counterattack. Just as Wingate was being attacked by his colleagues for the tone and content of his report, his protector Wavell was replaced with the far less sympathetic Sir Claude Auchinleck. Wingate grew depressed about the prospects for an inquiry and for his own career.

His malaria attack also worsened. On July 4, 1941, his fever was at 104 degrees when he stumbled back to his hotel room, locked the door, stuck a hunting knife into his neck, and fell to the floor. Colonel C. J. M. Thornhill, who was staying in the next room, heard the snap of the lock and the thump of the body hitting the floor through the thin wall between the rooms. After failing to break into Wingate’s room, Thornhill hurried to the manager for the master key. They entered just in time to keep Wingate from bleeding to death.

12

A psychological examination of Wingate, while he was in the hospital, concluded that his suicide attempt was brought on by a combination of depression, exhaustion, and illness. It also noted that he was likely to make a full recovery, physically and mentally. In September he sailed on a hospital ship to South Africa, Mediterranean waters being largely impassable at the time because of German and Italian control. From there he took a troopship back to Britain, arriving in November 1941. His legion of detractors thought he was finished. They were wrong.

*

Once home, Wingate’s doctors were inclined to see him as unfit for service; meanwhile his superiors seemed intent on court-martialing him for self-inflicted wounds. His recovery faltered and depression returned. But a Jewish doctor with Zionist ties took an interest in the case of

HAYEDID

and was able to bring in another colleague, Lord Thomas Horder, to consult. Horder had been personal physician to British monarchs and prime ministers in more than forty years of medical practice. He examined Wingate and came away convinced that he was still able to serve his country.

Thus Wingate was neither sacked nor court-martialed. But he had virtually no friends in the service, either, and prospects for a new posting appeared grim. At this point Wavell, now commander in India, reached out to him. British armies had taken terrible beatings in Malaya, Singapore, and Burma at the hands of Japanese forces that often employed infiltration methods not unlike those Wingate advocated. Perhaps Wavell wanted someone near him who thought along these lines. Or he may have acted out of compassion toward Wingate. Whatever his motives, in April 1942 Wavell arranged for Wingate to serve with him once more.

At the moment an invasion of India appeared imminent. The seemingly unbeatable Japanese forces would likely be assisted in such an attack by a rising of Indian nationalists’ intent on overthrowing British rule. Aside from planning to exploit a popular rebellion, the Japanese were also developing a regular force of disaffected Indians, recruited from among prisoners taken in earlier campaigns. They were to fight under the command of Chandra Bose, a sharp critic of Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent pursuit of independence, who had gone over to the other side. When the Japanese finally launched an invasion in 1944, Bose was part of it, at the head of about 150,000 Indians.

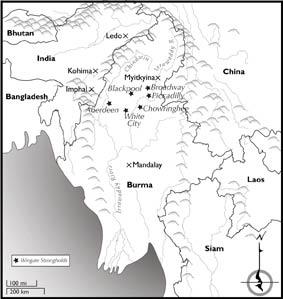

The China-Burma-India Theater

But in mid-1942 Wavell was in dire need of ideas for disrupting Japanese invasion plans. He could not count on reinforcements because in North Africa Auchinleck was being driven back to the gates of Cairo by Rommel. Wavell needed something else that would allow him to defend India actively but with limited resources. He needed the very sort of capabilities that Wingate held out the promise of providing.

Not one to miss such a seemingly miraculous opportunity for self-redemption, or to aid the one British military leader sympathetic to his ideas, Wingate quickly set to work bringing all his knowledge of long-range penetration and irregular warfare to bear on the problem of operating in Japanese-occupied Burma. He refused to believe that the enemy had an unbeatable edge in jungle warfare and began crafting the concept of operations that would, early the following year, lead to the first of two “Chindit” expeditions (“Chindit” comes from Wingate’s corruption of the Burmese

CHINTHÉ

, for “lion.”).