Inside Out

‘I laughed out loud so many times my wife thought that I had Tourette’s. It’s so well written, full of detail, self-deprecating

and funny. A seminal book – an intelligent, literate rock and roll memoir full of candour and wit’ Alan Parker

‘A real pleasure – a rich, funny and fascinating story. Nick is a wonderfully dry and laconic guide’ Peter Gabriel

‘The fact that this man can remember anything about the orgy he calls his career is a miracle – an amazing view of a life

most of us would kill for’ Ruby Wax

‘With a wit drier than an AA clinic, and a charm more disarming than a UN peace-keeping force, Nick Mason gives us a literary

drum solo par excellence’ Kathy Lette

‘There cannot be many stories left in rock that are as big as Pink Floyd’s. And I doubt whether anyone could tell this story

so well as the patient, witty man who watched it all unfold from his perch behind the drum kit’

Paul Du Noyer, founder of

Mojo

magazine

‘Mason could very probably have plied a successful trade as a writer. He has a measured, uncluttered style which he leavens

with a dry, original wit … he writes with the calm authority of someone who was actually present at the time … One of the

greatest stories in the pantheon of rock’ David Sinclair,

Guardian

‘A wise and witty addition to the canon of worthwhile rock biographies’ Ian Rankin,

Herald

‘As charmingly English as Pimm’s and heatstroke on a balmy summer’s day, few Pink Floyd fans will want to miss out on this’

Q

magazine

‘Debonair detachment, engaging wit, always readable’

Dominic Maxwell,

Time Out

‘Anything but a hymn of praise to the mighty Floyd. Mason’s drummer’s tale is unstintingly and amusingly disrespectful about

the band’ Robert Sandall,

Sunday Times

‘With scores of unseen shots from Mason’s personal archive, the book celebrates the little-noted fact that the Floyd were

a fabulously photogenic group’

Word

magazine

‘Tracing the band’s journey from those primitive beginnings to the stadium-filling sights and sounds that are Pink Floyd today,

the changes in rock ’n’ roll and its technology make this a strangely fascinating read’

Sunday Express

Nick Mason was born in Birmingham in 1944. He is – of course – best known as the drummer in Pink Floyd. When not behind the

drums Nick’s other passion is motor racing. He has raced extensively in both historic and contemporary cars and competed in

five Le Mans 24-hour races. In 1998 he wrote, with Mark Hales,

Into the Red,

a celebration of 21 cars from his collection of classic sports and racing cars (the book, updated and enlarged, was republished

as

Passion for Speed

in 2010). Nick has also written for a wide variety of publications including

The Sunday Times,

the

Independent, Time, Tatler, GQ, Autosport, Classic Cars, Red Line, Octane

and

Cars for the Connoisseur.

Philip Dodd is an author and editor who specialises in music and popular culture. He co-edited

The Rolling Stones: A Life on the Road

and, with Charlie Watts and Dora Loewenstein,

According to the Rolling Stones.

He was the interviewer and editor for

Genesis: Chapter and Verse,

and is the author of

The Book of Rock.

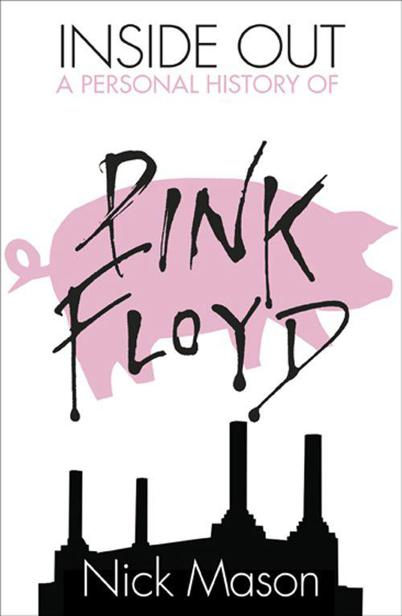

INSIDE OUT

A PERSONAL HISTORY OF

PINK FLOYD

NICK MASON

EDITED BY PHILIP DODD

P

HOENIX

CHAPTER 3

Freak Out Schmeak Out

CHAPTER 6

There Is No Dark Side

CHAPTER 10

Communications Failure

CHAPTER 11

Restart … And Restoration

CHAPTER 12

Wiser After the Event

R

OGER

W

ATERS

only deigned to speak to me after we’d spent the best part of six months studying at college together. One afternoon, as

I tried to shut out the murmur of forty fellow architectural students so that I could concentrate on the technical drawing

in front of me, Roger’s long, distinctive shadow fell across my drawing board. Although he had studiously ignored my existence

up until that moment, Roger had finally recognised in me a kindred musical spirit trapped within a budding architect’s body.

The star-crossed paths of Virgo and Aquarius had dictated our destiny, and were compelling Roger to seek a way to unite our

minds in a great creative adventure.

No, no, no. I’m trying to keep the invention to a minimum. The only reason Roger had bothered to approach me was that he wanted

to borrow my car.

The vehicle in question was a 1930 Austin Seven ‘Chummy’ which I’d picked up for twenty quid. Most other teenagers of the

time would probably have chosen to buy something more practical like a Morris 1000 Traveller, but my father had instilled

a love of early cars in me, and had sourced this particular car. With his help, I learnt how to keep the ‘Chummy’ operational.

However, Roger must have been desperate even to want me to lend it to him. The Austin’s cruising speed was so sluggish that

I’d once had to give a hitch-hiker a lift out of sheer embarrassment because I was going so slowly he thought I was actually

stopping to offer him a ride. I told Roger the car was off the road, which was not entirely true. Part of me was reluctant

to lend it out to anyone else, but I think I

also found Roger rather menacing. When he spotted me driving the Austin shortly afterwards, he had his first taste of my penchant

for occupying that no-man’s-land between duplicity and diplomacy. On a previous occasion, Roger had accosted Rick Wright,

who was also a student in our class, and asked him for a cigarette, a request Rick turned down point blank. This was an early

sign of Rick’s legendary generosity. These first, mundane, social contacts – during the spring of 1963 – contained the seeds

of the relationships we would enjoy and endure over the years ahead.

Pink Floyd emerged from two overlapping sets of friends: one was based around Cambridge, where Roger, Syd Barrett, David Gilmour

and many future Floyd affiliates hailed from. The other – Roger, Rick and myself – came together in the first year of an architecture

course at the Regent Street Polytechnic in London, which is where my recollections of our common history begin.

I had in fact already retired as a drummer by the time I arrived at the Poly (since rather grandly retitled the University

of Westminster). The college was then based in Little Titchfield Street, just off Oxford Street in the centre of the West

End. The Poly, in retrospect, seems to be from a bygone era, with old-fashioned wooden panelling reminiscent of a giant, utilitarian

public school. As far as I can remember there were no real onsite facilities, other than some tea-making equipment, but the

Poly – in the heart of the rag trade area around Great Titchfield and Great Portland Streets – was surrounded by cafés offering

eggs, sausage and chips up to midday, when steak and kidney pie and jam roly-poly would be the

menu du jour.

The architectural school was in a building housing a number of other related disciplines and had become a well-respected institution.

There was still a fairly conservative approach to teaching: for History of Architecture a lecturer would come in and draw

on the board an immaculate representation of the floor plan

of the Temple of Khons, Karnak, which we were expected to copy, just as they had been doing for thirty years. However, the

school had recently introduced the idea of peripatetic lecturers, and played host to some visiting architects who were on

the frontline of new ideas, including Eldred Evans, Norman Foster and Richard Rodgers. The faculty clearly had a good eye

for form.

I had strolled into studying architecture with no great ambition. I was certainly interested in the subject, but not particularly

committed to it as a career. I think I felt that being an architect would be as good a way to earn a living as any other.

But equally I wasn’t spending my time at college dreaming of becoming a musician. Any teenage aspirations in that area had

been overshadowed by the arrival of my driving licence.

Despite my lack of burning ambition, the course offered a variety of disciplines – including fine art, graphics and technology

– which proved to deliver a good all-round education, and which probably explains why Roger, Rick and I all, to a greater

or lesser degree, shared an enthusiasm for the possibilities offered by technology and visual effects. In later years we would

become heavily involved in everything from the construction of lighting towers to album cover artwork and studio and stage

design. Our architectural training allowed us the luxury of making relatively informed comments whenever we brought the real

experts in.