Inside Apple: How America's Most Admired--and Secretive--Company Really Works

Read Inside Apple: How America's Most Admired--and Secretive--Company Really Works Online

Authors: Adam Lashinsky

Tags: #Management, #Leadership, #Economics, #Business & Economics, #General

For Marcia, Ruth, and Leah

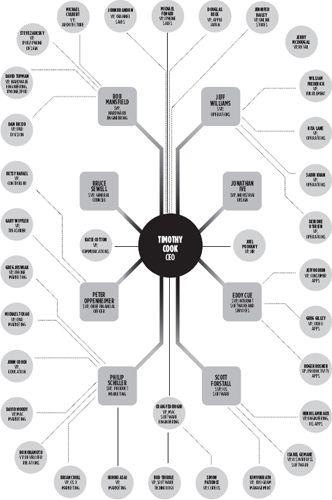

An unconventional org chart for an unconventional organization. CEO Tim Cook is at the center, and the reporting structure is just one of many ways that Apple differs from other corporations. This chart, conceptualized by graphic designer David Foster, is based on the author’s reporting in addition to some limited information Apple releases publicly.

O

n August 24, 2011, the day Steve Jobs resigned as chief executive officer of Apple, he attended a meeting of the company’s board of directors. He was gravely ill and had reached the conclusion that it was time to relinquish his post. He became chairman of the board that day, giving some hope to Apple’s employees, customers, and investors alike that he’d continue to exert influence on the company and be around for a while longer.

What Jobs loved most was products. Though he came that day to tell his directors in person that he was stepping down, he also knew he’d be able to see Apple’s latest offerings. Indeed, Apple was weeks away from introducing its newest iPhone, which would for the first time include the artificial intelligence–powered personal assistant software called Siri. Like the HAL computer in Stanley Kubrick’s

2001: A Space Odyssey

, Siri answered questions. It talked back to its owner. It began to fulfill

one of the promises of the computer revolution that Steve Jobs had helped start twenty-five years earlier, to harness the power of computers to improve human life.

Scott Forstall, Apple’s top executive for mobile software, was demonstrating Siri to the board when Jobs interrupted him. “Let me have the phone,” Jobs said, indicating that he wanted to try the personal assistant technology for himself. Forstall, who had worked for Jobs his entire career, first at NeXT and then at Apple, hesitated. He was an engineer with the theatrical flair, ambition, charisma, and raw intelligence of Jobs. Yet Forstall’s hesitation was warranted: The whole allure of Siri was that it learned its master’s voice oto ver time by adapting to quirks and absorbing personal details. The machine was like a baseball glove molded to its owner’s hand, and this particular unit knew Forstall. For all sorts of reasons—Jobs’s notorious short temper, this being an emotional day to begin with, the stress of handing over an unfinished product so close to its launch date—Forstall was reluctant to give the phone to Jobs. “Be careful now,” he said to a man who had never been careful in his life. “I have it pretty much attuned to my voice.”

Jobs, typically, wasn’t taking no for an answer. “Give me the phone,” he barked, prompting Forstall to walk around the table and hand over the device. The ailing Jobs, who had overseen the purchase of the start-up company that invented Siri’s technology, tossed the computer a couple of softballs. Then he turned existential, asking, “Are you a man or are you a woman?” Responded Siri: “I have not been assigned a gender, sir.” Laughter ensued, and with it some relief.

Siri’s gender-identification issues might have been a

lighthearted moment during a difficult meeting for the board, but when Jobs grabbed the iPhone prototype a jolt of anxiety undoubtedly coursed through Forstall. The scene illustrates many of the principles that make Apple great—but also different from most companies that are held up as models of good management. A giant company had concentrated its best manpower on a single product. The product had been developed in extreme secrecy, and the phone’s mechanics and design reflected an obsessive focus on detail. Also on display, for the last time, was a different breed of CEO, one who exhibited personality traits—narcissism, whimsy, disregard for the feelings of others—that society normally dismisses as negatives. But are they? For the way Apple does business and the way its executives manage the company fly in the face of years of business school teaching, begging the question: Is Apple’s success unique, or is Apple on to something the rest of the business world ought to be emulating?

It is fitting that Jobs’s last official act was reviewing an iPhone, given that Apple’s reinvention and domination of the smartphone category four years earlier had demonstrated the company’s and Jobs’s singular strengths. When it launched the iPhone in 2007, Jobs had turned Apple upside down to make it happen. He envisioned the iPhone as a revolutionary device combining the convenience of a smartphone with the music storage and listening capability of an iPod. If marrying these two inventions wasn’t enough of a challenge, there was the additional pressure that the resulting device needed to have a design-snob-worthy look, a user-friendly software interface, and a wow factor (touch-sensitive glass screen, anyone?).

The iPhone team at the time already was stretched

thin. Its very existence was putting strains on the rest of the company. Raids on other Apple groups, Macintosh software development in particular, had ground other projects to a halt; the latest version of the Mac’s operating system was delayed because the engineers writing the code had been switched to iPhone work. Resentment simmered among employees who were not chosen for the project because suddenly their electronic ID badges stopped working in areas that had been cordoned off and reserved for iPhone development. All Apple products are created equally; some are more equal than others.

An elite within an elite had been created, and the push to finish the iPhone was like an all-out mobilization for war. Engineers used macabre military terminology at Apple to describe the phase of product development when a la, ant whenunch approaches: the death march.

It is not every CEO who could ask and expect his most talented employees to work through the holidays, as Jobs did for years when the annual Macworld trade show was held shortly after New Year’s Day. But Jobs loomed larger than life for Apple employees. He had founded the company in 1976 with his chum Stephen Wozniak. He spearheaded the development of the Mac in the early 1980s, quit in disgust in 1985 when the CEO he’d selected to run the company reduced his authority, and returned triumphantly in 1997 to rescue a beleaguered company. Nearly a decade later, Apple reigned as the brightest light in the constellation of personal-technology companies, and its lodestar unquestionably was Steve Jobs.

Even when he wasn’t walking through the hallways of Apple, Jobs was a visible CEO. Sure, his office in the 1 Infinite Loop building was off limits to most of the com

pany. Yet Jobs was supremely present in the life of Apple. Employees of all stripes saw him in the company cafeteria, usually chatting with his design chief and alter ego, Jonathan Ive. They would spot him walking around campus, and they would see his car parked in front of IL-1. They watched his keynote presentations as eagerly as the public did so they could understand where their company was headed. Jobs may well have been unapproachable, and odds were that typical employees would never attend a meeting with him. But they believed that whatever they were working on would be seen, eventually, by “Steve.” For all flowed up to him, and his fingerprints were on everything important that Apple did.

On the eve of the original iPhone launch, Jobs was at the peak of his faculties and the top of his game. He had seemingly beaten cancer, having survived the removal of a malignant tumor from his pancreas two years earlier. He had disclosed little about his illness, other than that it wasn’t the predominant kind of pancreatic cancer, which kills quickly. In his unvarying outfit of black mock turtleneck, Levi’s blue jeans, dark socks, New Balance sneakers, and 1960s-style round spectacles, Jobs was fit and robust, his salt-and-pepper beard full and just a tiny bit bushy. Having turned 50 two years earlier, Jobs was on a tear. Apple had remade the music industry with the iPod and the iTunes music store. That year Jobs had sold his side project, Pixar, to Disney for $7.5 billion, making him the famed entertainment company’s largest shareholder, a member of Disney’s board of directors, and a billionaire several times over.

Jobs could see into the future better than anyone else in the technology industry. But four years later, after all

Apple accomplished between the first iPhone and the new model Jobs held in his hand, he refrained from asking Siri the existential question he knew was beyond its artificial intelligence yet of paramount importance: “What kind of company will Apple be after I’m gone?”

T

he death march that led to the iPhone was textbook Apple—favorites were played, key resources were diverted to a product that had captured the CEO’s interest, the hours were brutal, yet the work felt important. Could another company with annual sales of $108 billion have achieved a similar feat in the same time frame? Probably not unless it had a CEO who believed that he could change the world and his company could put a “dent in the universe.”

After his death at age fifty-six on October 5, 2011, Steve Jobs was rightly celebrated for his extraordinary contributions to the reordering of multiple industries. He . Bustriesrevolutionized no fewer than four: computers, music (through the iTunes Store and the iPod), film (through Pixar, which pioneered computer animation), and communications (with the iPhone). Having helped define the computer industry as a young man, he was well on his way to ushering in its successor. Months before his death, at the triumphant debut of Apple’s second iPad, Jobs declared the beginning of the “post-PC era”—meaning computing would no longer be confined to a desktop or laptop. In Apple, he oversaw a company whose products were world famous but whose methods were top secret.

Were Apple better understood, its fans and foes alike would see it as a giant jumble of contradictions, a

company whose methods go against decades of well-established management maxims. It’s as if Apple weren’t paying attention to what they’re teaching in business schools. In fact, it is not.