Influence: Science and Practice (29 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

A word of qualification is in order. There is no doubt that I was learning other things all the time that helped improve my sales. However, having experienced the speed of these changes firsthand, there is no doubt in my mind that no other single factor came close to “social proof from similar others” as the #1 reason for my 119.67% improvement.

Author’s note:

When the reader, who is a personal friend, first told me this stunning story during a face-to-face conversation, I think he could sense my skepticism. So, by way of supportive evidence, he has since sent me monthly records of his sales figures during the four summers he described—figures he had carefully recorded at the time and kept for decades. It should probably come as no surprise, then, that he teaches statistics classes at his home university.

“Chris, you can swim!” I said excitedly. “You can swim!”

“Yes,” he responded casually, “I learned how today.”

“This is terrific! This is just terrific,” I burbled, gesturing expansively to convey my enthusiasm. “But, how come you didn’t need your plastic ring today?”

“Well, I’m 3 years old, and Tommy is 3 years old. And Tommy can swim without a ring, so that means I can, too.”

I could have kicked myself. Of course it would be

to little Tommy

, not to a 6′2″ graduate student, that Chris would look for the most relevant information about what he could or should do. Had I been more thoughtful about solving Chris’ swimming problem, I could have employed Tommy’s good example earlier and, perhaps, saved myself a couple of frustrating months. I could have simply noted at the day camp that Tommy was a swimmer and then arranged with his parents for the boys to spend a weekend afternoon swimming in our pool. My guess is that Chris’ plastic ring would have been abandoned by the end of the day.

Monkey Die

Although we have already seen the powerful impact that social proof can have on human decision-making, to my mind, the most telling illustration of this impact starts with a seemingly nonsensical statistic: After a suicide has made front-page news, airplanes—private planes, corporate jets, airliners—begin falling out of the sky at an alarming rate.

For example, it has been shown (Phillips, 1979) that immediately following certain kinds of highly publicized suicide stories, the number of people who die in commercial-airline crashes increases by 1,000 percent! Even more alarming: The increase is not limited to airplane deaths. The number of automobile fatalities shoots up as well (Phillips, 1980). What could possibly be responsible?

One explanation suggests itself immediately: The same social conditions that cause some people to commit suicide cause others to die accidentally. For instance, certain individuals, the suicide-prone, may react to stressful societal events (economic downturns, rising crime rates, international tensions) by ending it all. Others will react differently to these same events; they might become angry, impatient, nervous, or distracted. To the degree that such people operate or maintain the cars and planes of our society, the vehicles will be less safe, and consequently, we will see a sharp increase in the number of automobile and air fatalities.

According to this “social conditions” interpretation, then, some of the same societal factors that cause intentional deaths also cause accidental ones, and that is why we find so strong a connection between suicide stories and fatal crashes. Another fascinating statistic indicates that this is not the correct explanation: Fatal crashes increase dramatically only in those regions where the suicide has been highly publicized. Other places, existing under similar social conditions, whose newspapers have

not

publicized the story, have shown no comparable jump in such fatalities. Furthermore, within those areas where newspaper space has been allotted, the wider the publicity given the suicide, the greater has been the rise in subsequent crashes. Thus, it is not some set of common societal events that stimulates suicides on the one hand and fatal accidents on the other. Instead, it is the publicized suicide story itself that produces the car and plane wrecks.

To explain the strong association between suicide-story publicity and subsequent crashes, a “bereavement” account has been suggested. Because, it has been argued, front-page suicides often involve well-known and respected public figures, perhaps their highly publicized deaths throw many people into states of shocked sadness. Stunned and preoccupied, these individuals become careless around cars and planes. The consequence is the sharp increase in deadly accidents involving such vehicles that we see after front-page suicide stories. Although the bereavement theory can account for the connection between the degree of publicity given a story and subsequent crash fatalities—the more people who learn of the suicide, the larger will be the number of bereaved and careless individuals—it

cannot

explain another startling fact: Newspaper stories reporting suicide victims who died alone produce an increase in the frequency of single-fatality wrecks only, whereas stories reporting suicide-plus-murder incidents produce an increase in multiple-fatality wrecks only. Simple bereavement could not cause such a pattern.

The influence of suicide stories on car and plane crashes, then, is fantastically specific. Stories of pure suicides, in which only one person dies, generate wrecks in which only one person dies; stories of suicide-murder combination, in which there are multiple deaths, generate wrecks in which there are multiple deaths. If neither “social conditions” nor “bereavement” can make sense of this bewildering array of facts, what can? There is a sociologist at the University of California in San Diego who thinks he has found the answer. His name is David Phillips, and he points a convincing finger at something called the “Werther effect.”

Free-Thinking Youth

We frequently think of teenagers as rebellious and independent-minded. It is important to recognize, however, that typically that is true only with respect to their parents. Among similar others, they conform massively to what social proof tells them is proper.

LUANN:

© GEC Inc. Distributed by United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

The story of the Werther effect is both chilling and intriguing. More than two centuries ago, the great man of German literature, Johann von Goethe, published a novel entitled

Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (The Sorrows of Young Werther)

. The book, in which the hero, named Werther, commits suicide, had a remarkable impact. Not only did it provide Goethe with immediate fame, but it also sparked a wave of emulative suicides across Europe. So powerful was this effect that authorities in several countries banned the novel.

Phillips’ own work has traced the Werther effect to modern times (Phillips, 1974). His research has demonstrated that, immediately following a front-page suicide story, the suicide rate increases dramatically in those geographical areas where the story has been highly publicized. It is Phillips’ argument that certain troubled people who read of another’s self-inflicted death kill themselves in imitation. In a morbid illustration of the principle of social proof, these people decide how they should act on the basis of how some other troubled person has acted.

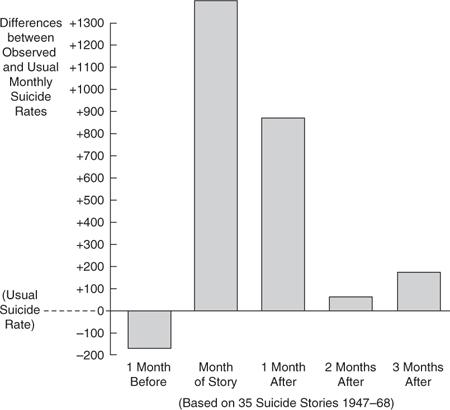

Phillips derived his evidence for the modern-day Werther effect from examining the suicide statistics in the United States between 1947 and 1968. He found that, within two months after every front-page suicide story, an average of 58 more people than usual killed themselves. In a sense, each suicide story killed 58 people who otherwise would have gone on living. Phillips also found that this tendency for suicides to beget suicides occurred principally in those parts of the country where the first suicide was highly publicized. He observed that the wider the publicity given the first suicide, the greater the number of later suicides (see

Figure 4.1

).

Figure 4.1

Fluctuation in Number of Suicides before, during, and after Month of Suicide Story

This evidence raises an important ethical issue. The suicides that follow these stories are

excess

deaths. After the initial spurt, the suicide rates do not drop below traditional levels but only return to those levels. Statistics like these might well give pause to newspaper editors inclined to sensationalize suicide accounts, as those accounts are likely to lead to the deaths of scores of people. More recent data indicate that in addition to newspaper editors, television broadcasters have cause for concern about the effects of the suicide stories they present. Whether they appear as news reports, information features, or fictional movies, these stories create an immediate cluster of self-inflicted deaths, with impressionable, imitation-prone teenagers being the most frequent victims (Bollen & Phillips, 1982; Gould & Shaffer, 1986; Phillips & Cartensen, 1986, 1988; Schmidtke & Hafner, 1988).

If the facts surrounding the Werther effect seem to you suspiciously like those surrounding the influence of suicide stories on air and traffic fatalities, the similarities have not been lost on Phillips, either. In fact, he contends that all the excess deaths following a front-page suicide incident can be explained as the same thing: copycat suicides. Upon learning of another’s suicide, an uncomfortably large number of people decide that suicide is an appropriate action for themselves as well. Some of these individuals then proceed to commit the act in a straightforward, no-bones-about-it fashion, causing the suicide rate to jump.

Others, however, are less direct. For any of several reasons—to protect their reputations, to spare their families the shame and hurt, to allow their dependents to collect on insurance policies—they do not want to appear to have killed themselves. They would rather seem to have died accidentally. So, purposively but furtively, they cause the wreck of a car or a plane they are operating or are simply riding in. This can be accomplished in a variety of all-too-familiar-sounding ways. A commercial airline pilot can dip the nose of the aircraft at a crucial point of takeoff or can inexplicably land on an already occupied runway against the instructions from the control tower; the driver of a car can suddenly swerve into a tree or into oncoming traffic; a passenger in an automobile or corporate jet can incapacitate the operator, causing the deadly crash; the pilot of a private plane can, despite all radio warnings, plow into another aircraft. Thus, the alarming climb in crash fatalities that we find following front-page suicides is, according to Phillips, most likely due to the Werther effect secretly applied.

I consider this insight brilliant. First, it explains all of the data beautifully. If these wrecks really are hidden instances of imitative suicide, it makes sense that we should see an increase in the wrecks after suicide stories appear. It makes sense that the greatest rise in wrecks should occur after the suicide stories that have been most widely publicized and have, consequently, reached the most people. It also makes sense that the number of crashes should jump appreciably only in those geographical areas where the suicide stories were publicized. It even makes sense that single-victim suicides should lead only to single-victim crashes, whereas multiple-victim suicide incidents should lead only to multiple-victim crashes. Imitation is the key.

In addition, there is a second valuable feature of Phillips’ insight. Not only does it allow us to explain the existing facts, it also allows us to predict new facts that had never been uncovered before. For example, if the abnormally frequent crashes following publicized suicides are genuinely the result of imitative rather than accidental actions, they should be more deadly as a result. That is, people trying to kill themselves will likely arrange (with a foot on the accelerator instead of the brake, with the nose of the plane down instead of up) for the impact to be as lethal as possible. The consequence should be quick and sure death. When Phillips examined the records to check on this prediction, he found that the average number of people killed in a fatal crash of a commercial airliner is more than three times greater if the crash happened one week after a front-page suicide story than if it happened one week before. A similar phenomenon can be found in traffic statistics, where there is evidence for the deadly efficiency of post-suicide-story auto crashes. Victims of fatal car wrecks that follow front-page suicide stories die four times more quickly than normal (Phillips, 1980).