Infinite Jest (99 page)

Authors: David Foster Wallace

I stood there by the slumped mattress for several moments of a silence so complete

that I could hear the street’s lawnmowers all the way out in the hall, then heard

the sound of my mother pulling out the vacuum cleaner’s retractable cord and plugging

it into the same bedside outlet the steel reading lamps were attached to.

I made my way over the angled mattress and quickly down the hall, made a sharp right

at the entrance to the kitchen, crossed the foyer to the staircase, and ran up to

my room, taking several stairs at a time, hurrying to get some distance between myself

and the vacuum cleaner, because the sound of vacuuming has always frightened me in

the same irrational way it seemed a bed’s squeak frightened my father.

I ran upstairs and pivoted left at the upstairs landing and went into my room. In

my room was my bed. It was narrow, a twin bed, with a headboard of wood and frame

and slats of wood. I didn’t know where it had come from, originally. The frame held

the narrow box spring and mattress much higher off the floor than my parents’ bed.

It was an old-fashioned bed, so high off the floor that you had to put one knee up

on the mattress and clamber up into it, or else jump.

That is what I did. For the first time since I had become taller than my parents,

I took several running strides in from the doorway, past my shelves’ collection of

prisms and lenses and tennis trophies and my scale-model magneto, past my bookcase,

the wall’s still-posters from Powell’s

Peeping Tom

and the closet door and my bedside’s high-intensity standing lamp, and jumped, doing

a full swan dive up onto my bed. I landed with my weight on my chest with my arms

and legs out from my body on the indigo comforter on my bed, squashing my tie and

bending my glasses’ temples slightly. I was trying to make my bed produce a loud squeak,

which in the case of my bed I knew was caused by any lateral friction between the

wooden slats and the frame’s interior’s shelf-like slat-support.

But in the course of the leap and the dive, my overlong arm hit the heavy iron pole

of the high-intensity standing lamp that stood next to the bed. The lamp teetered

violently and began to fall over sideways, away from the bed. It fell with a kind

of majestic slowness, resembling a felled tree. As the lamp fell, its heavy iron pole

struck the brass knob on the door to my closet, shearing the knob off completely.

The round knob and half its interior hex bolt fell off and hit my room’s wooden floor

with a loud noise and began then to roll around in a remarkable way, the sheared end

of the hex bolt stationary and the round knob, rolling on its circumference, circling

it in a spherical orbit, describing two perfectly circular motions on two distinct

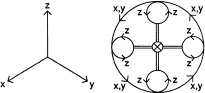

axes, a non-Euclidian figure on a planar surface, i.e., a cycloid on a sphere:

The closest conventional analogue I could derive for this figure was a cycloid, L’Hôpital’s

solution to Bernoulli’s famous Brachistochrone Problem, the curve traced by a fixed

point on the circumference of a circle rolling along a continuous plane. But since

here, on the bedroom’s floor, a circle was rolling around what was itself the circumference

of a circle, the cycloid’s standard parametric equations were no longer apposite,

those equations’ trigonometric expressions here becoming themselves first-order differential

equations.

Because of the lack of resistance or friction against the bare floor, the knob rolled

this way for a long time as I watched over the edge of the comforter and mattress,

holding my glasses in place, completely distracted from the minor-D shriek of the

vacuum below. It occurred to me that the movement of the amputated knob perfectly

schematized what it would look like for someone to try to turn somersaults with one

hand nailed to the floor. This was how I first became interested in the possibilities

of annulation.

The night after the chilly and sort of awkward joint Interdependence Day picnic for

Enfield’s Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery House, Somerville’s Phoenix House,

and Dorchester’s grim New Choice juvenile rehab, Ennet House staffer Johnette Foltz

took Ken Erdedy and Kate Gompert along with her to this one NA Beginners’ Discussion

Meeting where the focus was always marijuana: how every addict at the meeting had

gotten in terrible addictive trouble with it right from the first duBois, or else

how they’d been strung out on harder drugs and had tried switching to grass to get

off the original drugs and but then had gotten in even terribler trouble with grass

than they’d been in with the original hard stuff. This was supposedly the only NA

meeting in metro Boston explicitly devoted to marijuana. Johnette Foltz said she wanted

Erdedy and Gompert to see how completely nonunique and unalone they were in terms

of the Substance that had brought them both down.

There were about maybe two dozen beginning recovering addicts there in the anechoic

vestry of an upscale church in what Erdedy figured had to be either west Belmont or

east Waltham. The chairs were arranged in NA’s traditional huge circle, with no tables

to sit at and everybody balancing ashtrays on their knees and accidentally kicking

over their cups of coffee. Everybody who raised their hand to share concurred on the

insidious ways marijuana had ravaged their bodies, minds, and spirits: marijuana destroys

slowly

but

thoroughly

was the consensus. Ken Erdedy’s joggling foot knocked over his coffee not once but

twice as the NAs took turns concurring on the hideous psychic fallout they’d all endured

both in active marijuana-dependency and then in marijuana-detox: the social isolation,

anxious lassitude, and the hyperself-consciousness that then reinforced the withdrawal

and anxiety—the increasing emotional abstraction, poverty of affect, and then total

emotional catalepsy—the obsessive analyzing, finally the paralytic stasis that results

from the obsessive analysis of all possible implications of both getting up from the

couch and not getting up from the couch—and then the endless symptomatic gauntlet

of Withdrawal from delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol: i.e. pot-detox: the loss of appetite,

the mania and insomnia, the chronic fatigue and nightmares, the impotence and cessation

of menses and lactation, the circadian arrhythmia, the sudden sauna-type sweats and

mental confusion and fine-motor tremors, the particularly nasty excess production

of saliva—several beginners still holding institutional drool-cups just under their

chins—the generalized anxiety and foreboding and dread, and the shame of feeling like

neither M.D.s nor the hard-drug NAs themselves showed much empathy or compassion for

the ‘addict’ brought down by what was supposed to be nature’s humblest buzz, the benignest

Substance around.

Ken Erdedy noticed that nobody came right out and used the terms

melancholy

or

anhedonia

or

depression,

much less

clinical depression;

but this worst of symptoms, this logarithm of all suffering, seemed, though unmentioned,

to hang fog-like just over the room’s heads, to drift between the peristyle columns

and over the decorative astrolabes and candles on long prickets and medieval knockoffs

and framed Knights of Columbus charters, a gassy plasm so dreaded no beginner could

bear to look up and name it. Kate Gompert kept staring at the floor and making a revolver

of her forefinger and thumb and shooting herself in the temple and then blowing pretend-cordite

off the barrel’s tip until Johnette Foltz whispered to her to knock it off.

As was his custom at meetings, Ken Erdedy said nothing and observed everybody else

very closely, cracking his knuckles and joggling his foot. Since an NA ‘Beginner’

is technically anybody with under a year clean, there were varying degrees of denial

and distress and general cluelessness in this plush upscale vestry. The meeting had

the usual broad demographic cross-section, but the bulk of these grass-ravaged people

looked to him urban and tough and busted-up and dressed without any color-sense at

all, people you could easily imagine smacking their kid in a supermarket or lurking

with a homemade sap in the dark of a downtown alley. Same as AA. Motley disrespectability

was like the room norm, along with glazed eyes and excess spittle. A couple of the

beginners still had the milky plastic I.D. bracelets from psych wards they’d forgotten

to cut off, or else hadn’t yet gotten up the drive to do it.

Unlike Boston AA, Boston NA has no mid-meeting raffle-break and goes for just an hour.

At the close of this Monday Beginners’ Meeting everybody got up and held hands in

a circle and recited the NA-Conference-Approved ‘Just For Today,’ then they all recited

the Our Father, not exactly in unison. Kate Gompert later swore she distinctly heard

the tattered older man beside her say ‘And lead us not into Penn Station’ during the

Our Father.

Then, just as in AA, the NA meeting closed with everybody shouting to the air in front

of them to Keep Coming Back because It Works.

But then, kind of horrifically, everyone in the room started milling around wildly

and hugging each other. It was like somebody’d thrown a switch. There wasn’t even

very much conversation. It was just hugging, as far as Erdedy could see. Rampant,

indiscriminate hugging, where the point seemed to be to hug as many people as possible

regardless of whether you’d ever seen them before in your life. People went from person

to person, arms out and leaning in. Big people stooped and short people got up on

tiptoe. Jowls ground into other jowls. Both genders hugged both genders. And the male-to-male

hugs were straight embraces, hugs minus the vigorous little thumps on the back that

Erdedy’d always seen as somehow requisite for male-to-male hugs. Johnette Foltz was

almost a blur. She went from person to person. She was racking up serious numbers

of hugs. Kate Gompert had her usual lipless expression of morose distaste, but even

she gave and got some hugs. But Erdedy—who’d never particularly liked hugging—moved

way back from the throng, over up next to the NA-Conference-Approved-Literature table,

and stood there by himself with his hands in his pockets, pretending to study the

coffee urn with great interest.

But then a tall heavy Afro-American fellow with a gold incisor and perfect vertical

cylinder of Afro-American hairstyle peeled away from a sort of group-hug nearby, he’d

spotted Erdedy, and the fellow came over and established himself right in front of

Erdedy, spreading the arms of his fatigue jacket for a hug, stooping slightly and

leaning in toward Erdedy’s personal trunk-region.

Erdedy raised his hands in a benign No Thanks and backed up further so that his bottom

was squashed up against the edge of the Conference-Approved-Literature table.

‘Thanks, but I don’t particularly like to hug,’ he said.

The fellow had to sort of pull up out of his pre-hug lean, and stood there awkwardly

frozen, with his big arms still out, which Erdedy could see must have been awkward

and embarrassing for the fellow. Erdedy found himself trying to calculate just what

remote sub-Asian locale would be the maximum possible number of km. away from this

exact spot and moment as the fellow just stood there, his arms out and the smile draining

from his face.

‘Say what?’ the fellow said.

Erdedy proffered a hand. ‘Ken E., Ennet House, Enfield. How do you do. You are?’

The fellow slowly let his arms down but just looked at Erdedy’s proffered hand. A

single styptic blink. ‘Roy Tony,’ he said.

‘Roy, how do you do.’

‘What it is,’ Roy said. The big fellow now had his handshake-hand behind his neck

and was pretending to feel the back of his neck, which Erdedy didn’t know was a blatant

dis.

‘Well Roy, if I may call you Roy, or Mr. Tony, if you prefer, unless it’s a compound

first name, hyphenated, “Roy-Tony” and then a last name, but well with respect to

this hugging thing, Roy, it’s nothing personal, rest assured.’

‘Assured?’

Erdedy’s best helpless smile and an apologetic shrug of the GoreTex anorak. ‘I’m afraid

I just don’t particularly like to hug. Just not a hugger. Never have been. It was

something of a joke among my fam—’

Now the ominous finger-pointing of street-aggression, this Roy fellow pointing first

at Erdedy’s chest and then at his own: ‘So man what you say you saying I’m a hugger?

You saying you think I go around like to hug?’

Both Erdedy’s hands were now up palms-out and waggling in a like bonhommic gesture

of heading off all possible misunderstanding: ‘No but see the whole point is that

I wouldn’t presume to call you either a hugger or a nonhugger because I don’t know

you. I only meant to say it’s nothing personal having to do with you as an individual,

and I’d be more than happy to shake hands, even one of those intricate multiple-handed

ethnic handshakes if you’ll bear with my inexperience with that sort of handshake,

but I’m simply uncomfortable with the whole idea of hugging.’

By the time Johnette Foltz could break away and get over to them, the fellow had Erdedy

by his anorak’s insulated lapels and was leaning him way back over the edge of the

Literature table so that Erdedy’s waterproof lodge boots were off the ground, and

the fellow’s face was right up in Erdedy’s face in a show of naked aggression: