Indian Captive (21 page)

As the trader spoke, he did not look once at the white girl there before him. Leaning on his knee, she drank in all his words and tried to comprehend their meaning. Fort Duquesne, with the cold, gray stockade walls, burned to the ground! Only the chimney stacks of the log houses left standing. The barn, the well-sweeps, the garden, the peach tree—all were gone. The Frenchmen were gone as well as the Indians. Now the English, the red-coated English were there. She could never go back again to Fort Duquesne—to the man and woman who had wanted to keep her.

“Which side will the Iroquois take, English or French?” asked Fallenash, bluntly, looking toward the Chief. “You Senecas will have to make up your minds. You want to hold them English back on the Atlantic seaboard, don’t you? So far, you’ve been good friends of the French and they need you now worse than ever. You won’t let them English talk you over to their side, will you?”

“That is a question I cannot answer,” said the Chief. “The League of the Iroquois must decide. The People of the Long House must speak for themselves.”

“Well, if you desert the French,” said Fallenash, with a smile, “it means goodbye to all French agents and traders. Me—I ain’t on one side nor t’other. I like the Indians better. But when this fightin’ begins, I’ll have to run fast to save my hide. Maybe I’ll have to give up this wandering life and settle down somewhere—where there ain’t no tomahawks flyin’!”

“Will you be going back to Marsh Creek Hollow then?” asked Molly, quickly.

But the question was not answered, for Squirrel Woman’s hand grasped the girl’s shoulder and away she was hustled to Red Bird’s lodge.

Molly was determined to speak to Fallenash before he left the village. All night she thought over what she would say. All night she tossed and turned, trying to keep awake. At dawn, unheard and unseen, she crept from her bed and ran out the door. As she expected, the trader was already there. He was loading his pack-train as she came up.

“Take me with you, Fallenash!” she cried. “Oh, please take me away with you!”

“Why, gal, I can’t do that,” answered the trader seriously. “I feel mighty sorry for any white gal who’s been took by the Injuns and can’t git back to her folks again. But I can’t do nothin’ about it.”

Molly watched as the man adjusted the ropes of bark that bound the burdens to the horses’ backs.

“I could walk, if there’s no room to ride on the horses,” she said, hopefully. “Ever since the white people at Fort Duquesne wanted to keep me, I can’t seem to think of anything else. Somehow, I must get away from the Indians…I could stay with you till you go back to Marsh Creek Hollow again. I would help all I could and I can travel anywhere—I’m strong again, now.”

Old Fallenash glanced at the girl’s thin face and frame. Then he sat down on a stump and drew her down beside him. His weatherbeaten face folded into lines of anxiety and strain.

“I wish to God I could help you, Molly,” he said, in a solemn voice, “but I can’t. You see, I’ve got a trading-post on Buffalo Creek and that’s no place for a nice white gal. Sometimes the Indians get drunk and angry and they cut up purty lively.”

“I could hide till they went away,” suggested Molly.

“Then, there’s another reason,” Fallenash went on. “I have…well, you see…I have an Indian woman living with me and she’s not a very good housekeeper. It would be just another Indian home and not half as good as you have here. I know these Senecas well. They’ll be good to you. Besides, if I took you, it would make the Senecas angry. I want to go on livin’ a while yet. I don’t want to lose my scalp. I’m not ready to feel a tomahawk stickin’ in my back, either!”

“They would kill you?” asked Molly.

“They would kill me sure, if I took you away,” said Fallenash. “No, gal, you stay right here and try to be contented. If you just make up your mind to it, you’ll be happy enough. Say your catechism like your mother taught you, pray to God every day and try not to forget to speak in English.”

“I do! Oh, I do!” cried Molly. “Ma said I must never forget and I don’t mean to.”

“Don’t take it too hard,” Fallenash went on, with real sorrow in his voice. “It’s a fine, free, open life and you can be happy if you’ll just make up your mind to like it. The Indians don’t work half so hard as the whites and they get lots more joy out of life. In fact, I think Indian life is not half bad myself. I like it.”

“You do?” asked Molly, her face brightening. “Do you mean what you say?”

“I do,” said Fallenash. “That’s why I got me an Indian woman and live as much like an Indian as I can.” He paused, then continued: “Have you ever happened to think? The Indians don’t make you read books or do sums. They don’t make you knit and sew seams every minute. They don’t sit in church all day long. They don’t scold and think about their sins all the time.”

Molly’s thoughts flew back to home. Once there had been a time when knitting and sewing were irksome; when she had hated reading and doing sums. Betsey “took to” those things, but Molly bungled. If only now she could have a seam to sew or a stocking to knit—how well she would do it!

A shadow fell on her face as she spoke. “Oh, Fallenash, tell me. Do you think there’s any way I can ever get home again?”

“Well, of course, there’s always a chance somebody might come…but I doubt it. No, there ain’t no way,” replied Fallenash, firmly. “You’d best try to be contented here. Once these Senecas have adopted you, they’ll fight tooth and nail ’fore they’ll give ye up. No, you’d better just forget about goin’ home and be happy here.”

The girl’s thin white face fell again into despair. The trader with a conscience-stricken look of half-guilt, dug into his pack and brought out a shining string of glass beads. He leaned over and tied them about the girl’s neck.

“There!” he cried. “When you see them purty beads, just remember Old Fallenash would help ye if he could.”

Slowly he walked over to his waiting pack-train. At the signal of his shout, the horses started. The trader looked back at the white girl sitting on the stump, but she did not raise her head.

Running Deer

A

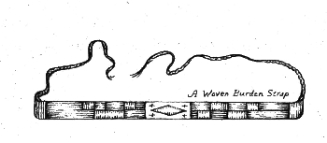

BURDEN-STRAP WITH MOOSE-HAIR

embroidery Corn Tassel shall have,” said Earth Woman, softly, as if talking to herself.

Molly had just come in. She lifted Blue Jay off her back. Her cheeks, touched by the chill of late autumn winds, glowed faintly pink. She smiled, but did not speak. She stretched her hands out to the welcome warmth of the fire. Then she unbound the Indian baby and set him on his feet.

“See! Blue Jay walks!” she cried in excitement. “His back has grown straight from the hickory board. His legs have grown strong and sturdy. Now he walks alone.”

The Indian woman chuckled. “He is not the first Indian baby who has learned to walk alone. My son was just so fine and strong when he was young.”

“But see!” cried Molly, laughing. “He turns his toes in, just like a woman. A man should not walk so.

“Ohé!”

cried Earth Woman. “Let him walk so. It is well for a boy to toe in. Then all the better will he walk on snow-shoes when the time comes.”

Molly began to beat time, chanting in a monotone. Blue Jay lifted first one foot, then the other. “See! He dances! Shining Star has taught him. She is indeed a wise mother.”

“After dancing,” said Earth Woman, smiling, “he will learn to swim. When the moon of flowers comes again, Blue Jay will swim in the river.”

“His name will have to be changed to Blue Trout then!” said Molly.

While Blue Jay, chattering happily, explored the lodge, Molly sat down by the fire and began braiding three strands of coarse bark fiber together, twisting it hard, to make a strong rope. A kettle, filled with narrow strips from the inner bark of slippery-elm, covered with ashes and water, boiled on the fire. Skeins made up of small fibers of bark which had been boiled, dried and twisted, were piled up near by. Balls of finely twisted basswood cord lay on the floor.

“Yes, a burden-strap decorated with moose-hair embroidery is none too good for Corn Tassel,” said Earth Woman again.

“But Blue Jay grows fast!” protested Molly. “I won’t need a burden-strap much longer. Soon he will be too large for the baby frame. When he goes all day long on his own two feet, I will have no burden to carry.”

“Your two sisters will soon see to that,” replied Earth Woman. “They will give you a

burden

frame instead of a

baby

frame. They will see that you carry game or cooking-utensils or bark or skins. They will never let you run idle. But a beautiful burden-strap can lighten a burden, no matter how heavy.”

A shadow crossed Molly’s face. “Why do Indian men make their women carry heavy loads?” she asked. “A white man never does so. The white man takes the burden away from the woman. He tries to spare her.”

“It is the Indian man’s duty to provide meat,” explained Earth Woman, “and to protect his family from the enemy. It is the Indian woman’s duty to make the home and keep it. “When they go together on a journey the men and boys must have their hands free, to be ready to kill game and to meet any lurking enemy. The women walk behind. They carry the young children and the burdens. It is the Indian way. The Indians have always done so.”

Earth Woman worked rapidly as she talked. She picked up loose bark fibers from the pile, two at a time, and twisted them together, by rolling them back and forth under the palm of her hand on the calf of her leg. A thin but strong cord was produced which she rolled into balls and put away for future use.

“A fine burden-strap is made by finger weaving,” Earth Woman went on, “with a needle of hickory. Only the finest strands of twine from slippery-elm bark are used. The belt in the center is the length of an arm and the width of three fingers. The ropes at each end are long and thin. Fine, delicate, but strong it shall be, with designs in bright colors for Corn Tassel’s forehead.”

A call came from outside.

“Enter!” cried Earth Woman, smiling happily. “More bark has come!” she added.

Shagbark and Turkey Feather entered the room, carrying loads of elm and basswood bark, which they had stripped from trees in the forest. They dropped the bark in heaps on the floor.

“More strings and ropes for Earth Woman to make” announced Shagbark. “A woman should never be idle. Now that the corn is harvested, it is well to provide work for her fingers.”

“Thank you for your kindness to one who has no man in her lodge,” said Earth Woman.

“I am to have a new burden-strap,” announced Molly, “with moose-hair embroidery. Earth Woman will make it for me.”

“Put many bright colors on it!” cried Turkey Feather. “Put blue for the sky, red for the falling leaves and yellow for ripe corn, the color of Corn Tassel’s hair.”

“Weave them together with kindness!” added Shagbark, quietly. “Then the burden on her back will never cut her forehead or give Corn Tassel pain!”

It seemed very quiet in the lodge when the man and boy went out. Earth Woman’s lodge was always quiet, for it was different from the others. She had no families living with her. In a room behind she kept her herbs, roots and supplies. No one but herself was allowed to enter. Molly knew now why it had always seemed so quiet during her long illness.