Independence (30 page)

Authors: John Ferling

Franklin alternated between sorrow for what need not have occurred—the British Empire was being wrecked “by the mangling hands of a few blundering ministers,” he said—and a sense that historical inevitability was being played out. As he saw it, “a new virtuous People, who have publick Spirit,” were coming of age and severing their ties with “an old corrupt” nation. Franklin saw no hope for the Olive Branch Petition, as Dickinson’s proposed appeal to the king was being called. It would “afford Britain one chance more of recovering our Affections and retaining the Connection,” Franklin remarked, but he was certain that Britain’s leaders had “neither Temper nor Wisdom enough to seize the Golden Opportunity.” He never doubted that American independence was on the horizon. “A separation will of course be inevitable,” Franklin said shortly after he entered Congress.

4

Nor could there be any doubt that he was pleased with what he saw as America’s inexorable march toward independence. Despite how much he loved London and hoped to live out his life there, once it became clear that Parliament and North’s ministry had “doomed my Country to Destruction”—to “murder our People,” was how he put it—he had cast his lot with America.

5

In letter after letter written to acquaintances in England in the first weeks after he entered Congress, Franklin alluded to “your Ministry,” “your Ministers,” “your Nation,” “your Ships of War.” When he referred to America he spoke of “our Seaport Towns,” “our Sea Coast,” “our Liberties.”

6

Franklin’s first task after entering Congress was to convince his colleagues that his support for America’s war was genuine. It took a few weeks, but by midsummer John Adams had aptly sized up his fellow congressman. Franklin supported “our boldest Measures,” Adams had concluded. In fact, he believed that Franklin “rather seems to think us too irresolute, and backward.” At present, Adams continued, Franklin believed America was “neither dependent nor independent. But he thinks that We shall soon assume a Character more decisive. He thinks, that even if We should be driven to … a total Independency … We could maintain it.” To which Adams added: Franklin “is … a great and good Man.”

7

Though not a commanding figure in Congress, Franklin was hardly inactive. Esmond Wright, a biographer, fittingly described Franklin as “the organizer of revolution” during that crucial summer of 1775. He had a hand in preparing Philadelphia’s defenses, planning a continental currency, securing munitions, and creating an American post office.

8

Franklin’s most daring act that summer was to call for organizing a national government under a constitution. Two decades earlier, while Pennsylvania’s representative at an intercolonial conference that met in Albany to prepare for the French and Indian War, Franklin had offered a plan of union for the thirteen colonies. London had not been happy with the idea of an American confederation, nor had any colony embraced the scheme. No American province had been willing to surrender even a smidgen of authority to a central government.

9

But in July, Franklin tweaked his twenty-year-old plan and presented it to Congress.

Franklin’s proposed constitution would have come close to creating an independent United States. Under his plan, Congress would have possessed the authority to levy taxes, create new colonies, conduct diplomacy, form alliances with foreign powers, and make war and peace. A plan of this sort never stood a chance of passage. Those who clung to the hope of reconciliation were horrified by it, and some who were ready for independence distanced themselves, fearing that deliberations would sow bitter, perhaps fatal divisions at a moment when unity was imperative. Franklin rapidly withdrew his scheme, claiming that he had merely wished to provide his colleagues with ideas to ponder. But, as was almost always true of Franklin, there was a hidden motive. His proposal was part of his campaign to convince skeptics that he was an ardent supporter of America’s war.

10

Vacuums do not last long in politics, and in June and July 1775 it was John Adams who stepped up to take the lead of those who were restive with the moderate course advocated by Dickinson.

Adams was anxious to redirect the delegates’ attention to Richard Henry Lee’s May 16 resolution calling for a national army, a proposition that had gathered dust for three weeks. The New England army camped outside Boston—the so-called Grand American Army—was not so grand. There were men aplenty, but the four provincial armies that made up the force were incapable of conducting a lengthy siege operation. Not only were there appalling shortages of arms, artillery, and ammunition, but New England also lacked the means of indefinitely paying the soldiery. Besides, the Yankees did not think that they alone should have to foot the bill for an army that was resisting British tyranny. British actions were an American problem, not a New England problem. It was clear, too, that some of the higher-ranking officers in the army were unfit. They owed their selection to politics, not merit. Furthermore, hardly any of the middle- and lower-grade officers were experienced soldiers. This army needed to be rebuilt, or “new modeled,” in the parlance of the day.

11

It would require the resources of all the American colonies and a leadership that shied away neither from initiating drastic changes nor from imposing the discipline necessary to mold the army into a decent fighting force.

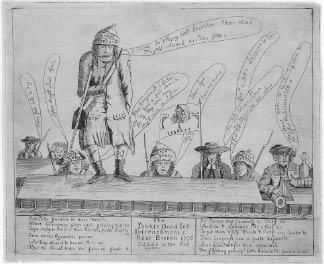

The Yankee Doodle Intrenchments near Boston. A British lampoon of the American siege of Boston and the amateur colonial soldiers. The siege began on the day after Lexington and Concord and continued until the British abandoned the city a year later. (Archive of Early American Images, John Corter Brown Library, Brown University)

As May slipped by without congressional action, Massachusetts activists wrote to their delegates in Philadelphia in what appears to have been an orchestrated campaign to secure change. The soldiers were defying orders, cried one correspondent. If something was not done soon, the army might turn into an armed mob and plunder civilians. What was needed, said another, was “a regular general to assist us in disciplining the army.” A writer cautioned, “Every days delay … will make the task more arduous.” One urged the appointments of Colonel Washington and Charles Lee “at the head” of the army. Even some officers in the army reported “the impossibility of keeping the army together, without the Assistance of Congress.” At the very moment that the Massachusetts congressmen were sharing these thoughts with their colleagues from outside New England, Massachusetts’s rebel assembly asked Congress to assume “the regulation and general direction” of the Grand American Army so that its “operations may more effectually answer the purposes designed.” It sent its request by express, which not coincidentally arrived as Congress was spinning its wheels over the wording of the petition to the king.

12

But Congress moved at a glacial pace. Before acting decisively, it discussed how to finance a national army, looked into securing gunpowder and other supplies, and solicited the thoughts of the authorities at home regarding who they preferred as officers in a national army.

13

John Adams was irritated by the delay. This “continent is a vast, unwieldy Machine,” he sighed. A good army has to be fashioned and quickly, he thought, for it alone offered “the most efficacious, Sure” means of securing “our Liberty and Felicity.” Samuel Adams was no less impatient, though he told his friends at home that something would soon be done. “Business must go on slower than one could wish,” he said. “It is difficult to possess upwards of Sixty Gentlemen, at once with the Same Feelings upon Questions of Importance.”

14

In mid-June, four days after Samuel Adams wrote his letter, John Adams brought matters to a head. He knew that “many of our staunchest” friends in New England thought the best means of obtaining a truly national army was through the appointment of someone from outside the region to command it. He knew too that many Southerners heartily agreed. Adams said privately that a “Southern Party” in Congress was not only suggesting that Southerners might refuse to serve in an army under Yankee leadership but was also backing Colonel Washington for the post of commander in chief. But some New Englanders were opposed to removing General Ward. They worried that New Englanders, who were certain to make up the lion’s share of the soldiery at least through the end of 1775, might only follow a commander who hailed from New England. Some also feared a harmful political backlash if Ward was dumped. The matter was further complicated by John Hancock’s longing to be chosen to head the army. The Massachusetts delegation was badly divided, and some—including Samuel Adams—were “irresolute,” as John put it.

Before Congress convened on June 14, John consulted Samuel Adams in the yard outside the Pennsylvania State House. They walked and talked at length on that warm summer morning, as John sought to persuade his more influential colleague of the wisdom of creating a national army headed by Washington. Aside from getting the job done so that the army could be improved and Congress could get on to other things, Adams wished to act because he was persuaded that Washington was the right man for the job. John subsequently recollected that Samuel did not agree, but neither did he disagree, and during that day’s session John, like Lee a month earlier almost to the day, moved that Congress “Adopt the Army” that was besieging Boston. Congress was ready to take this step, and it acted swiftly to take over the Grand American Army, transforming it into what the official congressional journal called the “American Continental Army,” or what almost immediately—and lastingly—would be known simply as the Continental army. Once that step was taken, John Adams was on his feet again, this time to address the issue of who was to be the army’s commander. There was a member of Congress, he said, “whose independent fortune, great Talents and excellent universal Character, would command the Approbation of all America, and unite the cordial Exertions of all the Colonies better than any other Person in the Union.” Thinking that Adams was speaking of him, Hancock listened with “visible pleasure,” Adams later recalled. But when Adams recommended Colonel Washington to command the new national army, Hancock’s expression changed suddenly to “Mortification and resentment.” The moment that Adams concluded his remarks, Thomas Johnson of Maryland formally nominated Washington to be the commander in chief of the Continental army.

15

Washington immediately left the chamber so that Congress could freely deliberate the motion. The delegates discussed the matter for the remainder of that day and half of the next, but their decision was never in doubt. As no record of Congress’s deliberation has survived, no one knows what was said. Years later Adams recalled that some objected to Washington’s appointment. That likely was true. The delegates must have spent some of the time discussing the ramifications of removing General Ward, but most of the discussion likely focused on learning as much as possible about Washington’s character from his fellow Virginians. It was already known that Washington was the right age—at forty-three he was young and strong enough to have a good chance of enduring a long war—and he had ample experience, having commanded Virginia’s army in the French and Indian War for nearly five years. What the congressmen really wanted to know, however, was whether Washington could be trusted with an army. The members of Congress knew that throughout history many generals had used their armies to make themselves dictators.

Virginia’s congressmen must have assured their colleagues that Washington was trustworthy, a conviction that many in Congress already shared, for they had been his associate at both congresses, observing him and even questioning him about his feelings regarding the subordination of the military to civilian authority. Washington passed every test. The congressmen saw him as “Sober, steady, and Calm,” no “harum Starum ranting Swearing fellow,” as one said. They thought him “sensible … virtuous, modest, & brave,” very formal and reserved, tough as nails, and possessed of an indomitable will. He commanded respect. One observer remarked that Washington “has so much martial dignity in his deportment that you would distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among ten thousand people. There is not a king in Europe that would not look like a valet de chambre by his side.” The capstone perhaps was that Washington was hardly a social revolutionary. His selection “removes all [sectional] jealousies” and solidly “Cements” the new American union, one congressman proclaimed. It was of no little importance that Washington was seen as sturdy enough to reconstruct the army and that he possessed the mettle to make citizens into good soldiers. He was appointed on June 15.

16