Independence (15 page)

Authors: John Ferling

The Virginians completed the trip in five days, but the delegates from Massachusetts were on the road for three weeks. The congressmen from South Carolina and Rhode Island were the first to reach Philadelphia. Those from North Carolina arrived last, not entering the city until nearly the last week in September, some twenty days after Congress had begun.

31

The journey of the Massachusetts congressmen was time-consuming in part because the delegates refused to travel on the Sabbath. But they also paused in nearly every town along the way to meet with noteworthy locals, hoping to demonstrate that they were not militant incendiaries. Furthermore, as most had never been outside Massachusetts, they spent considerable time sightseeing. They inspected gardens, toured the campuses of Yale and the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), and once in New York—where they lingered for a week—the deputies gawked at public buildings, fortifications, statues, the prison and hospital, churches, cemeteries, King’s College (now Columbia), and climbed into a tall church steeple for a panoramic view of the city.

32

As the Massachusetts delegates neared Philadelphia in the muted light of sunset on August 29, they were greeted by several congressmen from Pennsylvania and Delaware, who in turn were accompanied by a dozen or so leading citizens of the city. Forming a small caravan, the Yankees were escorted into Philadelphia and welcomed along the way by a scrum of well-wishers who waved happily. Though “dirty, dusty, and fatigued”—they had been on the road for more than eight hours that day alone—the rumpled Massachusetts congressmen were taken to the City Tavern on second street above Walnut for drinks and dinner, a long, festive session that extended past eleven P.M.

33

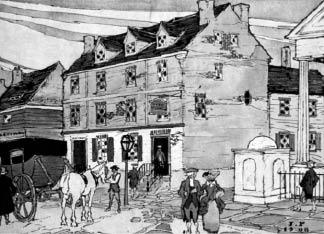

City Tavern of Philadelphia as depicted in an early twentieth-century color lithograph. Many congressmen resided at the City Tavern. Congress held its initial meeting here in September 1775 to decide on a site for its sessions. (Library of Congress)

Most congressmen found lodgings in private homes. The entire Massachusetts delegation rented rooms in the home of Jane Port on Arch Street. Washington and Richard Henry Lee lived at the home of Dr. William Shippen, Philadelphia’s most esteemed physician and Lee’s brother-in-law. Others were scattered here and there, including in taverns, the hotels of the day.

34

Probably many of the delegates were apprehensive that they might not measure up to the most talented congressmen from other colonies. John Adams imagined that Congress would be “an assembly of the wisest Men upon the Continent,” a gathering that would be a far cry from the caliber of the “sordid, venal Herd” ordinarily sitting in the Massachusetts legislature. He was not particularly confident that he would be adequate to the challenge. He knew law but fretted whether he was “fit for the Times,” that is, up to the great challenge that he would face. “I feel unutterable Anxiety,” he confided to his diary, adding, “God grant us Wisdom, and Fortitude” so that this congress would not in the end submit to British tyranny. “God forbid! Death in any Form is less terrible,” he declared.

35

As Congress was not scheduled to meet until Monday, September 5, the delegates who arrived early whiled away the time looking over the city. Several climbed the steep, narrow ladder into Christ Church’s tall steeple for what one deputy said was a “full View of the Whole City and of [the] Delaware River.” Most delegates were intrigued by Philadelphia. Many were unaccustomed to a large city, while those from Boston, New York, and Charleston were eager to see how the Pennsylvania metropolis compared with their own. A New Englander was amazed to find that “Wheat Fields crowd into the very Squares of the City,” by which he apparently meant that farms abutted the edge of Philadelphia. John Adams was struck by the “Regularity and Elegance of this City,” for unlike Boston, Philadelphia was a planned city that had been laid out in an uncomplicated gridiron pattern. The streets “are all equally wide, straight and parallel to each other,” Adams marveled. If in that respect Philadelphia differed from its counterparts, it was a typical walking city, quite similar to every American city of that day. More than six thousand houses and close to forty thousand inhabitants were squeezed inside a space that was only twelve blocks wide and some twenty-five blocks long. In an age before automobiles and mass transit, cities had to be compact so that the residents could daily get from their dwelling to their place of work, and back home again, by foot. Philadelphia was also typical of other cities—and quite unlike today’s American cities—in that neighborhoods were hardly segregated along social and economic lines. The small houses and shops of artisans frequently stood next to the fashionable homes of the affluent.

36

Not even Philadelphia’s “Exceeding hot, Sultry” weather, which the New Englanders found nearly unbearable, kept the delegates from sightseeing. Several toured the hospital and listened to a lecture on human anatomy by Dr. Shippen. Some went for an excursion to the “Cells of the Lunaticks,” where they found the incarcerated to be “furious, some merry, some Melancholly.” To his astonishment, John Adams discovered in what passed for the insane asylum an inmate whom he had once represented. “I once saved [him] … from being whipped … for Horse stealing,” Adams recalled. Others visited the shipyards and the poorhouse, which could accommodate five hundred residents. Many were taken with the four-hundred-yard-long city market, though a Yankee deputy opined that while the meat was excellent, the fruit and vegetables were inferior to those in New England. Nearly all toured the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). On Sundays, many worshipped in churches not to be found at home. Washington and John Adams, for instance, attended the local Roman Catholic Church, a first for the New Englander and probably for the Virginian as well.

37

Nearly every evening, socially prominent Philadelphians invited a delegate or two from several colonies to a sumptuous dinner party. At one affair, said a congressman, the table groaned with “Curds and Creams, Jellies, Sweet meats of various sorts, 20 sorts of Tarts, fools, Trifles, floating Islands, whipped Sillabubs &c &c—Parmesan Cheese, Punch, Wine, Porter, Beer &c &c.” On another occasion the guests had a dessert of “Melons, fine beyond description, and Pears and Peaches as excellent.” In between what John Adams referred to as the “incessant Feasts,” clusters of congressmen gathered over steaming pots of tea and cold tankards of beer to chat, and to size up one another. On September 1 the twenty-five delegates already in town spent a long evening dining together in a private room at the City Tavern. “My time is totally filled from the Moment I get out of Bed, until I return to it,” one congressman exclaimed, adding that much of each day was given over to “feast[ing] upon ten thousand Delicacies” and consuming spirits for hours on end. At times, some of the congressman drank too much. Adams said that at one party he “drank Madeira at a great rate.” He remained sober, or so he said, but he noted that Richard Henry Lee and Benjamin Harrison from Virginia got “very high.”

38

These festive occasions enabled the congressmen to become better acquainted. Each delegate knew the other members of his own delegation, but those from other colonies were for the most part total strangers. For a century and a half the colonists had looked across the sea toward the mother country, largely ignoring their neighboring provinces in America. Surprisingly little trade occurred between the colonies, and it, of course, was conducted by businessmen, not politicians. But businessmen often traveled and sometimes they became active in politics. For instance, Pennsylvania delegate Thomas Mifflin had met John and Samuel Adams a year earlier while on a business trip to Boston. Furthermore, some delegates had become acquainted with their soon-to-be colleagues through the committees of correspondence network. For a year or more, Samuel Adams had been exchanging numerous letters with leading political figures in several colonies, some of whom would serve in Congress.

39

Thus, it was largely but not entirely true, as one congressman remarked, that this conclave brought together “Strangers” who were unacquainted “with Each others Language, Ideas, Views, Designs” and who were also “jealous … fearfull, timid, skittish” in the company of one another.

40

Sometimes, too, the delegates struggled to overcome their own biased first impressions of those from other parts of America. The Yankee John Adams, for instance, immediately concluded that every New Yorker was rude and ungentlemanly. With some irritation he declared that they “talk very loud, very fast, and alltogether. If they ask you a Question, before you can utter 3 Words of your Answer, they will break out upon you, again—and talk away.”

41

Above all, the delegates were eager to discover the political outlook of their fellow deputies. Every word uttered, every toast offered, every sign conveyed by body language could divulge something of a colleague’s sentiments. John Adams had been in town less than twenty-four hours before he uncovered “a Tribe of People here” who were identical to those in orbit around Governor Hutchinson back in Massachusetts. One was Galloway, whom Adams instantly marked as identical in his thinking to those in Boston who had defended the Stamp Act back in 1765. On the other hand, Adams was delighted with Richard Henry Lee, who confided—presumably while he was sober—that he favored the repeal of all British taxes and the Intolerable Acts, the removal of the British army from American soil, and sweeping reforms in the mother country’s regulation of colonial commerce. Adams got the impression that most in the Virginia delegation shared Lee’s convictions, leading him to pronounce that those Southerners were filled with “Sense and Fire [and] Spirit.”

42

No one was at a greater disadvantage than Galloway, as Congress was meeting in his province. Legions of enemies that he had made in the course of twenty years in Pennsylvania politics appear to have spoken ill of him while meeting with deputies from other colonies. On the afternoon that the Massachusetts delegation had neared Philadelphia, Dr. Benjamin Rush, a leading physician in the city, had been among those who had ridden out to greet the New Englanders. He boarded the Yankees’ carriage, said John Adams, and immediately “undertook to caution us” about Galloway. Thomas Mifflin and Joseph Reed, a Philadelphia lawyer, showed the Massachusetts delegates about town and, while at it, enlightened them about Galloway’s past record, portraying him as a “Tory” who could be counted on to defend British policy. John Dickinson, whom Galloway had kept off Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation, frequently came to town to converse with the congressmen, and he entertained several at Fairhill, his nearby country estate. It hardly stretches credulity to imagine that Dickinson spoke with disfavor about Galloway in the course of these conversations.

43

Even before Congress formally met, Galloway was a marked man, at least among the more radical delegates.

Politicians all, the congressmen were struggling to discover what actions the Continental Congress might take, and what they might have to do to steer the assembly in what they thought was the proper direction. The congressmen knew that each colony was opposed to parliamentary taxation of Americans, but where most provinces stood on the issue of the limits of Parliament’s authority was far from clear. As eight of the colonies had instructed their delegates to vote for a trade embargo, that step seemed a certainty, though no one knew whether Congress would lean toward a total or partial boycott. Nor did anyone know what Congress would decide about how the boycott was to be enforced.

44

No one knew whether a majority would favor condemning all, or only some, of the Intolerable Acts. None knew how Congress would define the rights of Americans, or if Congress might be willing to relinquish some rights that colonial assemblies had previously claimed. To be sure, none knew whether Congress would consent to take steps to prepare for the possibility of war.

On September 5, almost four months to the day since word of the Intolerable Acts had reached Boston, the delegates to the First Continental Congress assembled at the City Tavern in Philadelphia. Their first order of business was to select a permanent meeting site. As politicians are wont to do, they made that seemingly uncomplicated matter into a test vote. Galloway offered the Pennsylvania State House. His rivals rallied behind Carpenters’ Hall. (A week earlier John Adams had noted in his diary that while touring the city, he had “visited … the Carpenters Hall,

where the Congress is to Sit

,” an intriguing remark that suggests delegates from several colonies must have colluded days before to thwart Galloway on this issue.)

45

As the State House was more spacious, it is likely that nearly everyone thought it the more desirable site, but the vote was seen as an assessment of Galloway’s strength. Congress chose to meet at the recently constructed Carpenters’ Hall, a Georgian brick building that served as a guildhall for tradesmen. The bottom floor included a spacious room, large enough for Congress’s sessions, while a library dominated the second story. The building was set back from Chestnut Street, offering privacy and quiet, and a colorful garden—suitable for exercise and conversing—was merely a step outside its rear door.

46