Incense Magick (19 page)

Authors: Carl F. Neal

Tags: #incense, #magick, #senses, #magic, #pellets, #seals, #charcoal, #meditation, #rituals, #games, #burning, #burning methods, #chaining, #smudging, #herbal blends, #natural, #all-natural

If you have a censer that can be handled while in use, carry your prepared censer to the eastern quarter along with a small container of your selected incense powder. Sit with your back to your altar, facing the eastern quarter. If your censer cannot be moved, sit before your altar with the censer between you and the eastern quarter, so you can look to that point on your circle while the censer is in your line of sight. Add a tiny pinch of incense to the charcoal. Control your breathing (I like to

inhale for four seconds through my nose, hold for two seconds, and release my breath for four seconds through my mouth for most incense work, then wait another two seconds before beginning to inhale again). Allow the scent of the smoke to penetrate you on the inside, from your lungs outward. Also allow it to penetrate from the outside as the smoke swirls around your body.

As you immerse yourself in this enchanted air, open your mind to that element. Let the smoke take you where it wants you to go. Watch the swirling eddies and currents in the air and allow the energy to wash over and through you. As you do so, think about the powers of air. What messages have they for you? How does the element of air interact with the other elements to make your life complete? You can continue this exercise as long as it is productive. At some point, no matter how trained or experienced you may be, humans reach a point of overload. Stop as soon as you see this possibility approaching. The more often you do this invocation, the more insight and relaxation you will find in the process.

Rituals for Moist Incense

Unlike most forms of non-combusting incense, moist incense tends to smolder very slowly. As long as you keep the heat underneath the incense at a low level, one pellet of moist incense can smoke for ten minutes and leave its scent for more than an hour after it has gone out. As a result, I sometimes use a modified form of “air mixing” by placing two pellets adjacent to each other over the heat. The scents tend to blend as soon as they leave the censer, so it isn't the same experience as true air mixing. The work that I do with moist incense is generally focused on adding incense to the censer only once. If you use a source of strong heat (such as “self-lighting” charcoal), the pellets will burn away very quickly and you will need to scrape the charcoal and replenish the incense frequently.

Here is a recipe for one basic type of moist incense that I make myself. It is simple and you will be amazed at the results. Even the most novice incense maker can successfully make moist incense that will amaze all who happen to smell it. This recipe is reprinted from my first book,

Incense: Crafting and Use of Magickal Scents.

If you want to explore moist incense making in more depth or are interested in making many other forms of incense, I think you might enjoy reading that book. The charcoal used in this recipe is a step to significantly cut the curing time of the incense. You can leave the charcoal out (I would replace it with wood powder) but that will extend the curing time considerably. Traditionally, this type of incense would be rolled and then sealed in a container and buried for a year or more. You should only use low-scent charcoal for moist incense. Never use “self-lighting” charcoal for incense making.

2 tsp. red cedar powder

¾ tsp. clove powder

½ tsp. charcoal

¼ tsp. benzoin

½ tsp. oak moss

½ tsp. rosemary powder

(up to) 1½ tsp. honey

Grind all of the dry ingredients to a fine powder. You might find it easiest to add all of the dry ingredients into a large pestle and grind them to a blended powder with the mortar. Before adding the honey, you should sift all the dry ingredients through a fine mesh. Use only real honey and beware of “honey-flavored syrup” (which is just corn syrup and flavoring). Add the honey a tiny bit at a time. The listed amount of honey is a very loose suggestion. You should add just enough honey to bind the dry ingredients into a single ball of incense. After each drop of honey is added, knead the incense carefully to make certain the honey is evenly dispersed throughout the incense.

Ideall,y you will be able to gather the mixture into a smooth ball. If there is too much honey in the mixture, you might find it difficult to roll. Once you have rolled the incense (be aware, even perfectly proportioned uncured incense will be very sticky), place it into a plastic bag and seal it after pressing out all the air in the bag. If your mixture is too sticky to roll, you can still scrape it off your gloves into a bag. In some of the workshops I've done, we've even taken gloves covered in particularly sticky mixtures and just turned the gloves inside out. With the opening of the glove tied tightly, the mixture will cure normally.

If you included the charcoal in the recipe, it will be ready to open in four to seven days. If you make a blend without charcoal, I wouldn't consider burning a test sample of the incense until it had aged at least three weeks. You will see the texture of the incense change as it cures in the plastic. Once you can open the bag and easily handle the incense (it will have lost 90 percent of its stickiness), break it into pea-sized pieces and roll into a smooth ball. Put the individual pellets back into a sealed container for storage. Only remove the number of pellets that you plan to use at any one time and keep the rest sealed. If kept in an airtight container, the incense will continue to improve as it ages. The longer it cures, the more blended the scents will become.

Incense Meditation

This is the most general meditation included in this book. It is easily modified to fit any contemplation need, but I prefer it as an “open” meditation, as it is written here. This is not an elaborate ritual at all and is well suited for use outside a circle. This is a slightly modified version of a morning mediation I did for a very long time. Set aside ten minutes in your busy morning schedule and your whole day will often flow in pleasant and unexpected directions.

Take a few moments to prepare your censer. Sift the ash and use an unlit charcoal brick to make an impression in the ash that will hold the burning charcoal. Hold the charcoal with a pair of tongs and light it in the flame of a candle. Once the charcoal is glowing on all corners you can place it into the impression in the ash. If you have been using a mica plate or ceramic tile, you can place that atop the charcoal. For best results, bury the burning charcoal once the brick is glowing all over its surface. Use this time as the charcoal is being prepared to clear your mind. One good method to accomplish this is to focus on your breathing. Count the seconds and focus on nothing but putting your breathing into proper rhythm (see

page 155

for a sample breathing pattern).

It is best to sit before adding the incense. Once your charcoal and optional plate or tile is in place, add one or two pellets of moist incense. You can use a single pellet, two of the same scent, or two different scents. I wouldn't use more than two scents for any one meditation.

Once you move your hand away from the censer, place both hands in your lap. If you are a highly visual person, you might benefit from watching the smoke, but I prefer to close my eyes and let the incense become the focus of my attention. Simply allow the smoke to enter through your nose as you practice controlled breathing. After a few sessions you will find yourself falling into the appropriate breathing without any conscious control on your part.

Use the focus of breathing to clear your mind of all other thoughts. Once you are able to let go of the conscious control of your breathing, you can set your mind free. This is the process I use to “listen” to incense and aromatics, and it is a wonderful way to start any day. If you have the kind of crazy mornings that so many families do, get up a few minutes early and use this meditation before anyone else is awake to disturb you. This type of regular meditation will reveal many surprising things to you once you learn to quiet your mind and listen to the energies around you. This is especially true if you learn to listen to your incense.

A Goddess Invocation (Bast)

Bast is the goddess of Upper Egypt. Although generally pictured as a delicate house cat, she also takes the form of a great cat prepared to defend her children. For this invocation, I like to use a moist incense containing catnip and palo santo wood, but any incense that you feel is appropriate will work just fine. If nothing else, the simplest moist incense made from honey and yellow sandalwood is a fine choice.

After casting a circle, if you choose to use one, and invoking all of the elements, you may call to Bast and ask for her help in the work that you plan to do. As she is my patron goddess, this is something that I do frequently. Occasionally I follow an invocation similar to this one and do nothing more than offer my thanks for all that is given to me. Sometimes that process can lead me to tasks I was not aware that I needed to complete.

Before adding the incense pellet(s) to your censer, call upon Bast to work with you:

Great Goddess Bast

Patron Goddess of cats and

fierce protector of her children

We/I invite you to this circle we/I cast this night

Please bring to us/me your wisdom, your compassion, and your empathy

That we/I might be blessed with your energy

and guidance in all that we/I do here

Please accept this meager offering

to your mighty spirit.

Once the invocation and offering has been given, place the moist incense into your censer. Allow the scent to fill the space. To further raise energy and draw the power of Bast, you may wish to chant:

Join us/me Goddess, enter here tonight

Bring us/me your wisdom and power

If this is your will

You can continue to chant as long as you feel power raising. Be aware that this type of chanting can draw a great deal of energy and results in a very warm room when performed indoors. Once you feel the strong presence of Bast, move on to your other work. Be certain to thank the goddess any time you ask for her help or energy in any of the working that you do. When your work is done and you are releasing other powers, such as the elements, release Bast before any others. “Go if you must, stay if you will,” is a traditional way to release any power.

Invoking Earth Power

I have always felt that moist incense, especially traditional Japanese nerikoh, is closely tied to earth powers. This invocation is very similar to the Invoking Air meditation given in the powdered incense section, and it is aimed at the same purpose: to draw powerful elemental energy into your circle while forming a stronger personal bond and understanding of that element.

Generally when one is working with elemental powers, it is common to work within a magick circle. If this is your choice, then perform this meditation when you invoke the northern quarter of your circle. If you prefer to do this as a stand-alone meditation, you need not draw upon the other elements. The former method is preferred when calling upon earth powers to aid in the work you are doing, while the latter is better as a meditation on the nature and relationship with earth.

Carry your censer to the northern quarter of your circle or, if you are doing this outside a circle, place it so that you can face north and the censer is between you and the northern horizon. Light your charcoal if you have not already done so. While it is always important to ground yourself anytime you are working magick, I think it is especially important when working with earth energies. With that in mind, carefully ground yourself and focus on your breathing for a few moments to quiet your mind.

Add a single moist incense pellet to the heat and focus on the censer. Try to position the censer so that you are sitting, facing north, looking down on the censer so that you can see both it and the ground upon which it rests.

I believe you can enhance this process even further if you use a stone or clay censer placed directly on the ground. Clear your mind and allow your eyes, and even your nose, to see the earth energies gathered at your censer. If you are using this meditation to draw energy into your circle, focus on the ground and visualize earth energy coming up around your censer and into the circle. If you are using this as a meditation, you can watch the energy gather and pool around you, absorbing into you. Earth energy is warm and heavy and is extremely comforting.

Non-combustible incense has many uses in magick. It is the most popular way to incorporate incense into ritual magick. It offers scent, dancing smoke, and a level of control that is difficult to achieve with self-combusting incense. You do have a trade-off, naturally, as non-combustible incense requires an external heat source; is most subject to interference from breezes; and generally requires more paraphernalia. For the ease of preparation and more precise control it offers, non-combusting incense is the perfect choice in many situations.

9

Asian-Style

Incense Burning

N

owhere has the art of the censer and charcoal been brought to a higher level than in Asia. Whether in China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, or other parts of the Far East, the preparation and use of the censer is an art form. The techniques and approaches used in Asian censers are easy to apply to Western practices as well. Censers for magick, ritual, or just for pleasure all benefit from the detail and traditions of the Far East.

I want to preface this section by acknowledging that I am no Japanese incense master. I have not been formally schooled in kodo (and yes, there are many formal schools for learning kodo, including at least two in the United States), although I have been lucky enough to participate in several kodo ceremonies. What follows is my own interpretation of kodo and is definitely not the way that a Japanese master would teach the ceremony. Again, if you are interested in performing a true traditional kodo ceremony, there are several excellent books on the topic as well as videos and organizations that can give you traditional instruction.

In addition to the highly formal kodo ritual, there is also a wide assortment of incense games that have come from traditional Japanese sources. These games are easy to adapt to Western incense practices and you'll find Westernized versions of several of these games later in this chapter.

Critical Elements of Asian-Style Burning

This approach to incense use relies on the availability of appropriate materials and, to do it well, a great deal of practice. Fortunately, it's easy to translate many of the tools and techniques for any use from casual to high magick. There are three critical components to emulate the kodo-style of burning: ash, charcoal, and a mica plate.

It is also important to understand that traditional kodo is focused entirely on a single aromatic: aloeswood. Naturally, this implies a limitation that isn't actually present. When I first learned that kodo only used aloeswood (with the occasional inclusion of sandalwood), I felt that it would be quite limited. That belief grew from a lack of experience with aloeswood. As I gathered experience with this remarkable aromatic and came to understand that this was not a limitation, I also opened up my thinking with regards to

all

aromatics. Aloeswood and sandalwood in particular, but all aromatics to differing degrees, vary widely from plant to plant, valley to valley, region to region, and continent to continent. Learning to detect the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) differences between different types and grades of aloeswood not only helps refine and improve one's incense palate but heightens awareness of the subtle differences in all aromatics.

David Oller once told me, in the midst of a heated discussion, that he could create at least a hundred different sandalwood combinations, each with a unique scent, out of his personal collection alone. I believed him then and I believe him now. Of course, we were debating the value of recipes for incense blends

1

and not the subtleties of scents in sandalwood, but no matter. His statement is still very accurate and important for any user (be it an incense “connoisseur” or a complete novice) to understand and always remember.

Ash

One of the keys to the Asian approach to censers is something I've mentioned before: ash. Ash is a key to all aspects of loose incense burning in Asia. The ash most commonly used, often called white ash due to its light color, is generally pure ash from bamboo. Because of this, the ash has virtually no scent even when heated. Ash used in rituals (such as the kodo ceremony) is generally of the highest quality and therefore produces the least scent. It is often sold in fancier containers and labeled “ceremonial ash.” Even “ordinary” white ash is excellent for any censer.

Charcoal

A second important part of the Asian approach to loose incense is the charcoal. Unfortunately, we in the West have gotten used to low-quality “self-lighting” charcoal. The problems with this type of charcoal are many fold because self-lighting charcoal is loaded with potassium nitrate (also called saltpeter). This creates several problems. The potassium nitrate creates a foul odor. Even if the charcoal is allowed to sit and “vent,” its smell is still horrid. Any aromatics you burn on such charcoal will blend their scents with that foul odor. This is always a problem for incense users, but it is particularly bad if you are trying to enjoy some very expensive aloeswood or sandalwood!

We know that self-lighting charcoal burns very hot, and this is the exact opposite of what incense users need, especially for kodo. High temperatures cause aromatics to burn very quickly. A sliver of aloeswood could cost $30 or more, which would be gone in a matter of seconds on self-lighting charcoal. It will burn so quickly that you might never be able to pick out the scent of the wood at all.

Self-lighting charcoal can even harm your ash. The scent from the saltpeter can permeate the ash and cause the ash itself to smell. Although the scent can be reduced through proper care, it is far better to keep the ash scent-free rather than trying to repair it after the fact. The ash from self-lighting charcoal smells almost as much as the burning charcoal does.

Rather than using this low-quality self-lighting charcoal, proper Asian charcoal is made from low-scent ingredients with no potassium nitrate. It is made from pure charcoal powder (usually bamboo, but sometimes other woods are used) and a binder so that it can be shaped into bricks. Low-scent charcoal generally burns just as long as self-lighting but at a much lower temperature. Beyond the lower temperature, Asian charcoal is also safe to bury below the surface of the ash in the censer. As mentioned in chapter 7, burying the charcoal is an excellent way to gain control over the temperature of the burning aromatics.

Mica Plate

A final key factor in Asian-style loose incense is a mica plate. This thin layer of mica (a mineral) is generally edged with silver (to make it easier and safer to handle) and placed atop the ash over the burning charcoal. This provides a flat surface to hold the aromatics. The plate also serves to heat the aromatics evenly, as the mica will heat to a consistent temperature over the whole plate.

The combination of ash, low-scent charcoal, and a mica plate give incense users nearly complete control over the temperature of the aromatics. As the next section will show, this ancient approach to incense burning is perhaps the best system ever devised short of modern electric incense heaters. Some of us think that the ancient approach is still superior to modern heaters.

Preparing the Censer

As with many other processes that have caught the Asian imagination, incense burning has been elevated to high art. The preparation of the censer has many rituals associated with it, but I will only touch on these lightly in their traditional role. As you will see, these traditions lend themselves well to magickal use. Although I will discuss and show several of these traditions, any readers who wish to learn more about Asian incense traditions will find several excellent books on the topic. Check this book's bibliography for the titles of the best-known books on the topic.

To prepare a censer in the kodo-style, you will need two round censers (a ceramic censer called a koro is traditional and its shape will produce the most satisfactory result), ash to fill the censers, two identical bricks of low-scent charcoal, tongs (small pliers will usually work), a toothpick or skewer, a pair of tweezers, and a mica plate (a small ceramic tile could be substituted).

Light the Charcoal

Never use self-lighting charcoal for this style of burning. Traditionally, the charcoal is held in metal tongs over a flame. Turn the charcoal regularly to allow all the edges to light. The charcoal is then placed in a separate censer just for allowing the charcoal to properly warm. This allows the charcoal to glow evenly and completely and to discharge any minor scent it might have. When the censer used for actual incense burning is prepared, the burning charcoal is transferred to the prepared censer.

Prepare the Primary Censer

Once the charcoal is lit and resting in a safe place, the primary censer can be prepared. Begin by filling the censer roughly two-thirds full of ash. Again, white ash is best, but any low-scent ash can be used. If you are recycling ash (which is an excellent idea) you might want to screen it first. The simplest way to accomplish that is to pour the ash through a wire mesh sifter. I don't recommend sifters that use an arm to force the ash through the screen (like many flour sifters have) as any resins or other soft materials can become trapped in the mesh and prove very difficult to remove. It is better to pour the ash into the sifter and gently shake it until all of the ash has passed through. This step also helps to trap additional air in the ash which will improve the burning characteristics of the charcoal buried beneath the ash.

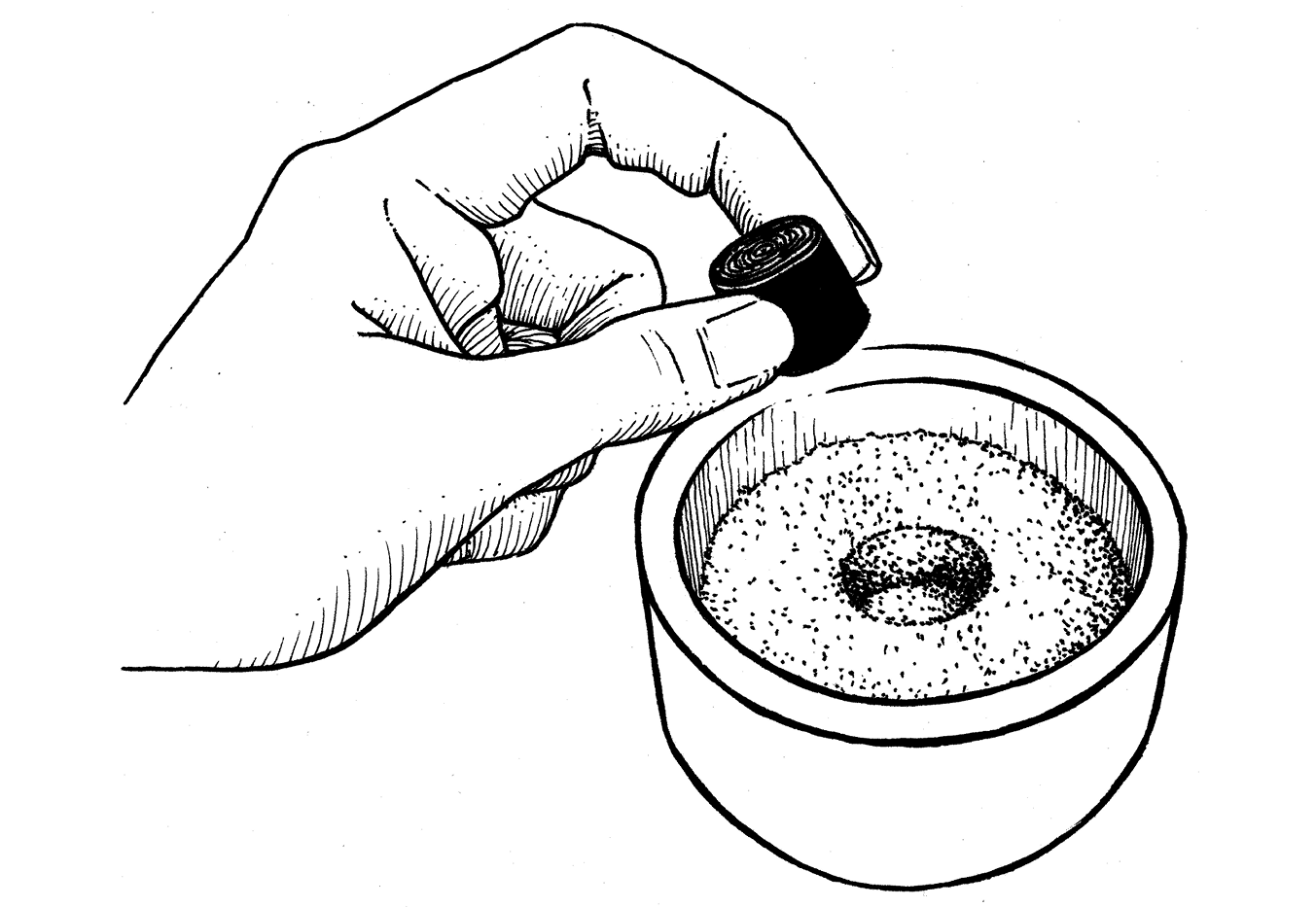

You can sift the ash directly into your censer, but it is usually easier to sift it onto a sheet of paper and then pour the ash into the censer. Whichever way you choose to do it, once the ash is in the censer, lightly tap the censer on a solid surface to slightly compact the ash. Don't overdo it or you'll lose some of the benefits of sifting the ash. Once the ash is in the censer, level it out (most easily accomplished by gently shaking it side to side). Use an unlit charcoal brick the same size as the one you've lit to make an impression in the center of the ash. The impression should be as deep as the charcoal brick is tall. Carefully remove the charcoal brick (perhaps using tongs) and it will leave a perfect space for the burning charcoal.

Ash-filled censer with an impression for charcoal.

Place the Charcoal and Build the Volcano

Once the burning brick is completely glowing and the ash is prepared in the primary censer, you can transfer the charcoal. Obviously, the charcoal is hot and can easily burn you. Use tongs, pliers, or (more traditionally) metal chopsticks to transfer the charcoal into the impression in the charcoal. Place it into the impression very carefully so that it is level with the top of the ash or slightly below the level.

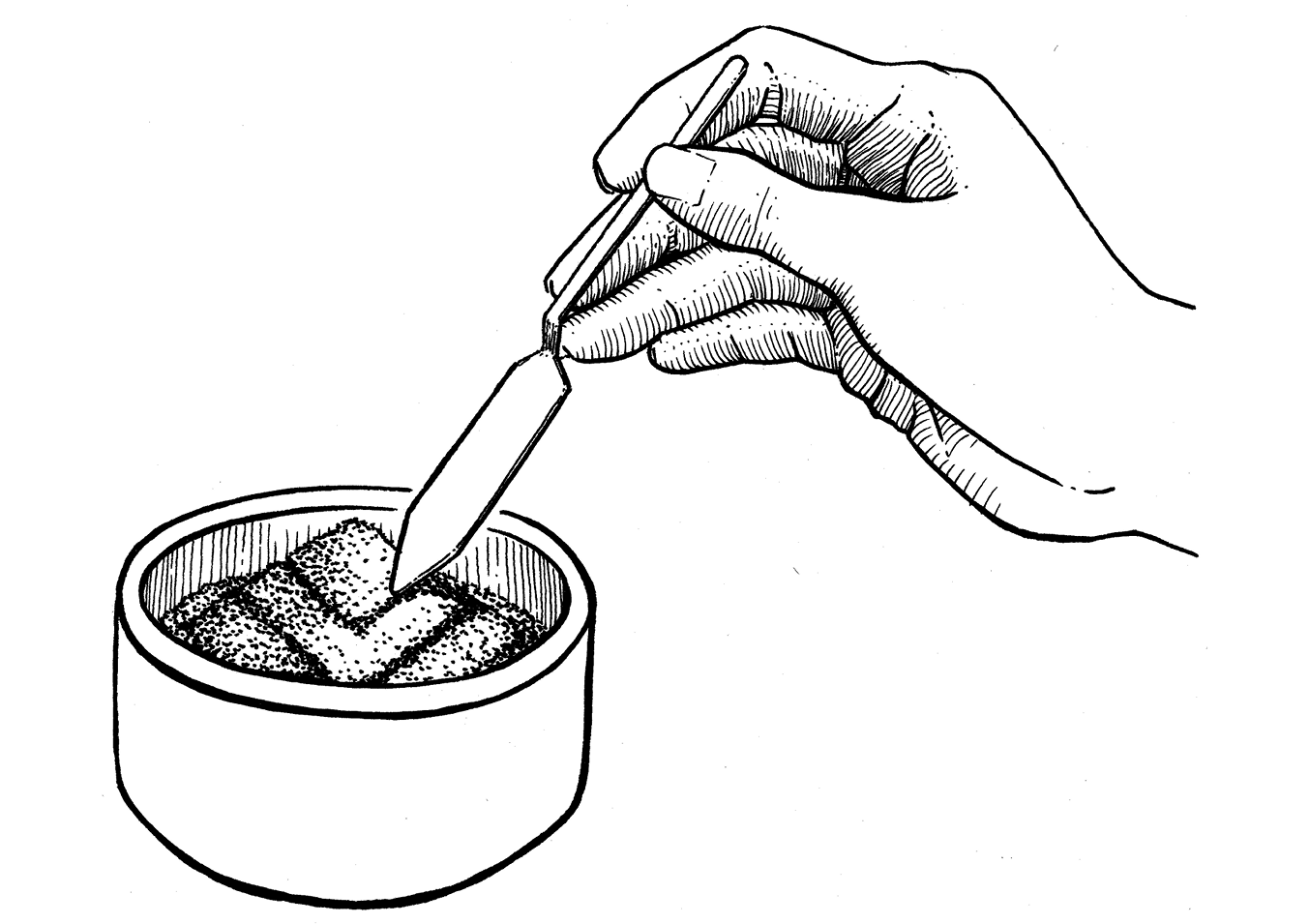

At this point comes the first truly delicate part of the process. Carefully begin to mound ash over the top of the charcoal. The goal with this step is to create a “mountain” or “volcano” of ash over the top of the charcoal. You want to create a tapered mound of ash that comes to a point directly over the burning charcoal. This volcano should be roughly 1½ inches tall, although the height should be adjusted to fit the censer you are using. The volcano should never extend beyond the top of your censer.

Ash “volcano.”

Once the ash volcano has been formed, you can then create many different traditional and non-traditional shapes in the ash. Simple parallel lines or lines that are drawn in opposition to one another are often added. You can also draw magickal symbols or forms into the volcano if you desire, just make certain to draw quickly as the charcoal is burning away under the ash. Once you've drawn any desired symbols in the ash, a hole needs to be put through the center of the ash to the charcoal. Use a skewer or toothpick to penetrate the center of the volcano all the way down to the surface of the charcoal.