In the Valley of the Kings (5 page)

Read In the Valley of the Kings Online

Authors: Daniel Meyerson

Tags: #History, #General, #Ancient, #Egypt

As everyone waited above, he frantically searched the passage, looking for some indication of a hidden staircase or tunnel or shaft leading—he hardly knew where, since by all indications and signs, this should be the burial chamber. It had been carefully sealed, hidden hundreds of feet underground, protected with a twelve-foot-thick wall—but it was empty. His searching uncovered only a tiny miniature coffin secreted in a wall. Its inscription indicated the king for whom the tomb was dug: Mentuhotep I, one of the first kings of the Eleventh Dynasty, a pharaoh who reigned at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom (ca.

2010 BC

).

Perhaps the tomb had been dug in antiquity to throw would-be robbers off the scent. Perhaps the statue wrapped in linen represented some arcane ritual burial, a magical rite to ward off death. Perhaps building the huge mortuary temple at the foot of the cliffs (erected by this same king) caused him to change his plans and dig his tomb elsewhere in the cliffs. Or perhaps the tomb was abandoned for some other reason lost to history.

Whatever the reason, Carter now had to climb into the brilliant sunlight to publicly acknowledge his defeat. Among the onlookers were those only too ready to laugh at the presumption of this outsider, for jealousy among excavators and scholars was as intense as among opera divas—or thieves.

Covered with dust, he began to make his apologies, but quickly

the compassionate and fatherly Maspero intervened. As Carter was to say of the moment: “I cannot now remember, all the kind and eloquent words that came from Maspero, but his kindness during this awful moment made one realize that he was really a worthy and true friend.”

Maspero’s private feelings matched his public stance. He wrote in a private letter: “Carter had announced his discovery too soon to Lord Cromer. Lord Cromer came to be present at his success and he is now very saddened at not having been able to show him anything of what he foretold. I console him as best I can, for he truly is a good fellow and he does his duty very well.”

Though Carter would later remember Maspero’s kindness with gratitude, at the moment he was shattered. Nothing could console him. He remained at the tomb until late at night, going over and over the underground rooms in his bewilderment.

The echo of chatter and speculation faded as the intruders went their way. They left the place to the heartbroken excavator on the threshold of his magnificent discovery—and to its tutelary goddess, Meretsinger, She Who Loves Silence.

Carter was inconsolable—but the irony was that he would also be inconsolable later, when he was finally granted his heart’s desire. For twenty years after this fiasco—two full decades later, in 1922—he would find his tomb. But then it would not come to him by beginner’s luck, the accident of a fallen horse, or by any other gambler’s sleight of hand. It would come through grueling work and suffering and faith: faith in the powers that he knew had been granted him, though the world looked at him askance.

He would be the first to uncover a tomb that had been sealed for thousands of years. He would stand in the presence of a pharaoh lying in a solid gold coffin under a gold mask of incomparable beauty: Tutankhamun Nebkheperure—Lord of the Manifestation of the Sun, the Strong Bull, Victorious, Eternal.

Here, in the small, dark rooms of this tomb, he would labor for

ten long years, carefully bringing out thousands of precious objects, among them some of the most moving works of ancient Egyptian art. After which he would spend the rest of his life famous, wealthy—and embittered.

He would never excavate again. A solitary figure, idle, angry, withdrawn, he would live out his last days on the terrace of Luxor’s Winter Palace. With a touch of madness? Or perhaps with truth? He would tell anyone who would listen that he knew where the much-sought-for tomb of Alexander the Great could be found. But, he would add with spite, he would take that secret with him to the grave: The world did not deserve to know it.

Between the young boy sketching his smelly lapdogs and the raging old man was a lifetime spent in grueling, unsparing work. Yes, he would discover his tomb. But the gods would give him glory, not peace. He would fulfill the words of the New Kingdom tomb curse: “Let the one who enters here beware. His heart shall have no pleasure in life.”

1*

With the establishment of the Egyptian Antiquities Service in 1858, permission to excavate had to be sought from the Department of Antiquities. Such permission, called a concession, marked out the area to be explored and stipulated the terms under which the excavator could dig and how he or she had to proceed in the event of a tomb being discovered. In 1902, the American banker Theodore Davis took on the concession to dig in the main Valley of the Kings, a concession he would not relinquish until shortly before World War I.

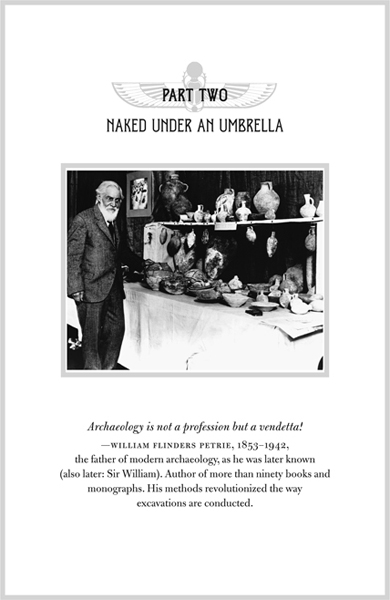

PREVIOUS PAGE: Sir Flinders Petrie standing beside a table with some of his rare archaeological findings. © CORBIS

1892

Cairo: The Hotel Royale, where Carter, just off the

boat from England, is introduced to Petrie

THE FIRST TIME THE YOUNG CARTER MET HIM (IN A CAIRO HOTEL)

, Petrie was dressed in his “city” clothes: a worn but still passable suit. It was buttoned up, showing just a bit of the cravat, which was knotted anyhow beneath the high white collar in fashion then. He was unforgettable with his large, generous features; his full beard and shock of black hair brushed back over a high, swarthy brow; his enormous dark eyes set wide apart; his thick lips compressed in thought. His expression was very alert—his features were stamped with intellectual passion as surely as greed or lust can be read on other men’s faces.

In all the photographs from this decade, Petrie seems always to be wearing this same suit! Somehow there is an incongruity about these respectable clothes of his, as if someone had dressed up an Old Testament prophet in a suit, cravat, and high collar. It is as if at any moment his large, athletic body will burst open the worn-out cloth, revealing his larger-than-life presence.

It is more fitting for him to be naked, like some heroic figure sculpted by Michelangelo. When working inside one or another of the pyramids, at Giza or Hawara or Lisht, he would sometimes have to wade through half-flooded chambers (the water level having risen over the centuries). Or to crawl through lower passages where the heat was unbearable. At such times—for example, when

measuring Khufu’s great pyramid at Giza, he would “emerge just before dawn, red eyed, oxygen deprived, smelling of bat dung”—and in his birthday suit.

Which was how Carter saw him the second time the two met: As desert winds covered Petrie with a fine layer of sand, the father of modern archaeology stood in an irrigation canal, naked under an umbrella. He had just finished soaking the salt off some ancient pots, and now he was submerged up to his shoulders in the river, trying to cool off.

In this pose, he looked “rather like a water buffalo,” as Amelia Edwards, another witness of the nude Petrie, affectionately recalled. As director of the Egyptian Exploration Society, Ms. Edwards had much to do with Petrie; she fell in love with the bearded buffalo-scholar—though it was “as hopeless as loving a young obelisk,” she sighed in a letter to a friend.

He was as single-minded and chaste as a monk. At least for the first half of his life, he was alone with his scarabs and pots and pyramids. Until he finally met his match in the brilliant and beautiful young Hilda Urlin, the only women he held in his arms were ones he dug up from tombs and burial pits.

He was indifferent to everything except archaeology. Sleep was a waste of time. Clothing—another unfortunate necessity—must be worn until ragged. As for food: The young hopefuls who worked with him might learn much (Carter, Mace, Weigall, Quibel, Wainwright, Engelbach, and Brunton among them—the list is long). But they would suffer. They would sleep on straw pallets or wooden packing cases, and they would starve.

“I have known him to knock a hole in a tin of sardines and drink the oil before opening it…. I can’t go on with Petrie I have got so weak and horrid from this beastly food,” Arthur Weigall wrote to his wife, a complaint echoed by a chorus of hungry young archaeologists.

“Petrie was a man of forty-one with … the agility of a boy,”

Charles Breasted remembered. “His clothes confirmed his universal reputation for being not only careless but slovenly and dirty. He was thoroughly unkempt, clad in ragged dirty shirt and trousers, and worn-out sandals…. He served a table so excruciatingly bad that only persons of iron constitution could survive it; even they had been known on occasion stealthily to leave his camp in order to assuage their hunger by sharing the comparatively luxurious beans and unleavened bread of the local fellahin [peasants]…. The fact remains that he not only miraculously survived the consistent practice of what he preached, but established in the end a record of maximum results for minimum expenditure which is not likely to be surpassed….”

There were no tinned sardines, however, at the Hotel Royale, where Petrie was staying when he first met Carter. Though it was in a good quarter of Cairo, Ezbekia, it was not the exclusive, fashionable Shepherd’s Hotel. However, it had the same chef as Shepherd’s, as the man had saved up and gone into business for himself. Thus, Petrie’s visitors were treated to the last word in culinary refinements when they attended his nightly archaeological salon.

The many distinguished scholars, the epigraphists and geologists, the linguists and historians and excavators, not to mention Petrie’s half-starved students—everyone—as the talk turned on mummy-bandaging techniques and nummulitic limestone, could gorge himself to his heart’s content under Petrie’s disapproving, fanatic eye.

Carter remembered those gatherings in his journal. He was awed by the company and afraid of Petrie, “a man,” he noted, “who did not suffer fools.” It was a phrase Amelia Edwards also used about him, adding fondly that that was because “he was born more alive than most men.”

Be that as it may, at these meetings Carter was silent while Petrie talked. Petrie was in his forties, while Carter was still in his teens, and the older man theorized, pronounced, and advised about

everything. Everything! From the subtleties of scarab styles to excavation guards who snore to the name of the pharaoh of the Exodus. How to deal with ancient, fragile textiles, with carbonized papyri, and with fleas.

Covering many subjects with lightning speed, Petrie held forth like an oracle in a cryptic, staccato style, backing into tables and overturning chairs when he became excited. Even the sound of his voice was oracular: It had a high and eerie quality, the way the Sibyls were said to have sounded in their trances. But though Petrie was, like them, a being possessed, there is a simpler explanation for his quavering, reedy tones—an act of violence he met with at the beginning of his career.

“Exploring on foot and alone in the Sinai desert,” his colleague Gertrude Caton-Thompson related, “he was approached by three Bedouin in that empty land. He scented danger, and quickly threw his wallet by a backhand movement into a bush unobserved. They fell on him and nearly strangled him while he was searched. Then, empty handed, they went on their way, leaving him temporarily speechless,” his throat injured, his voice permanently changed.

The young Petrie got up and—not forgetting to retrieve his wallet—continued his explorations in “that empty land.” It is a barren landscape, with red sandstone cliffs and deep gorges and endless sand dunes broken at long intervals by a lone flowering broom tree or sometimes, in the crevice of a boulder, a hardy, sweet-smelling herb.

He had set out to study what he called the “unconsidered trifles” that would remain important to him throughout his career. Sinai’s turquoise mines yielded as much knowledge to him as a royal tomb (as would the alabaster quarries of Hatnub and the granite mines of the Hammamat).