In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" (46 page)

Read In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" Online

Authors: Phil Brown

Tags: #Social Science/Popular Culture

Have I mentioned, by the way, how many comics who came out of the Borscht Belt refuse even to discuss that life? I believe it is because of the aforementioned lowbrow nature of the joints. Also because

borscht

is a buzz word for “Hebe”—that is to say, for a comic who can play only to Jews.

“Dah premise is insulting,” says one man who made his career in the mountains. “I consider myself a

univoisal

comedian.”

“Borscht Belt? Rodney was never in the Borscht Belt,” somebody else’s publicist says. “He played a few

dates

, but they never went for him. His background was strictly the clubs in New York.”

What a pity, to remove oneself from a scene so rich and wild.

Consider: in two counties alone, 524 hotels that require entertainment, which translates into new material

seven nights

a week—guests stay on the average at least two weeks. What a lure for comics, what a pressure cooker, what a pull!

And the excitement, in those days before Beverly Hills. Henny Youngman and his band getting into food fights in the dining room or turning a fire hose on a guest. Gas rationing, during the war, when the comic who had a decent car could get himself a job—provided he schlepped along a few other acts—and when Jack Carter, going to the mountains, would pray, “

Please

, not another dance act, to have to sit five hours under a pile of dresses;

please

, not another magician, to have to sit in the back with the goddamn birds.”

Picture it: Singer’s Restaurant, which is still there, where Dick Shawn and Jackie Mason and Jerry Lewis and Myron Cohen and Don Rickles and Red Buttons and Joey Bishop hung out after a show and you could always tell, according to Milt Ross, a veteran mountain comic, who was doing good and who was not according to what was on their plate. (“If they were eating a sandwich which was not so expensive, they were not doing so good; if they were having Chinese, which cost, they were doing okay.”)

Their acts, within Borscht Belt parameters, are varied, though perhaps it is best to let Ross, who began his career in the Yiddish theater in New York City and now works out of Miami, call the shots.

“Jerry Lewis, whose father, Danny Lewis, was a comedian and his mother was the accompanist, did a mime record act, Jerry in those days wasn’t so great,” says Ross. “Dick Shawn didn’t do any Jewish at all except he sang ‘Roumania.’ Eddie Schaeffer did a good mountain act, but a good mountain act isn’t that good; always talking about fire escapes, and what did people not from New York know about fire escapes? Jack Carter did just jokes, one after the other; he’d either kill them or he’d die. Myron Cohen was a wonderful storyteller, wonderful; the Yidluch

loved

him,” he says.

The

Yidluch

—the first generation; the Jews just off the boat. But the majority of Borscht Belt comics were second-generation, and they were a restless crew. They ripped off hit movies and Broadway shows, writing their own versions. (“

Awake and Sing!, The Informer

—we’d take a play and chop it up…. Imagine how ridiculous it must have looked,” says Murray. “We had the nerve of burglars in those years.”) They tired of doing the same old gags from burlesque and worked up their own material. Sid Caesar begins doing his double-talk routines; Milt Ross picks up some social satire from Max Liebman. And of course there are the mountain classics, some of them very painful, born who knows where on the stage or around the pool.

Two Polish Jews, captured by the Nazis, are about to be executed. Very smooth SS officer approaches. Asks the first Jew about to die if he can offer him anything: a blindfold, a brandy, a cigarette. First Jew starts cursing him out. “Nazi Pig,” he begins, “I spit in your face. I spit on your blindfold and cigarette and brandy. You are mindless scum now.You will be remembered as scum by history. You—” His friend grabs him and interrupts him.

“Abie,” he says, “why look for trouble?”

With the Fifties, the area is changing. The New York State Thruway is making the mountains more accessible, and comics are coming up for one-nighters and weekend dates rather than for the whole season. Air travel is becoming available to the middle class, and small hotels are folding, and the large ones, such as the Concord, Grossinger’s, the Nevele, and Brown’s, can make a Zero Mostel, an Eddie Fisher, an Alan King.

And there is something else that is going on and that is important: television. It will, as it disseminates everything, spread the mysteries of the Borscht Belt across America. Sid Caesar, with producer Max Liebman and former Borscht Belt social director Mel Brooks, will score a television hit in 1949 with the

Admiral Broadway Revue

show, then really make his name with

Your Show of Shows

. Milton Berle, a Borscht Belt comic in spirit, though he comes out of the burlesque houses of New York, will spread New York Jew into everyone’s living room—will, according to some, be the fellow who makes Jewish humor safe and takes it into the mainstream.

“Jewish humor didn’t change. The country changed,” says Alan King.

“Mel Brooks,” he says, “The Twelve Thousand Year Old Man, that was about as Borscht Circuit as you could get, and was a terrific success: “

How many children do you have?” “Sixty-five hundred and forty—four hundred doctors.”

“And the Two Thousand Year Old man talks like an old Jewish man, y’-know,”says King. “He didn’t talk like John Gielgud.”

And so, in its old incarnation, the Borscht Belt is finished. Perhaps a half dozen big hotels remain in the Catskills, with stars flying in for dates the way they’d go to Vegas. The old hotels were burned down for insurance money; the young comics are getting their start in comedy clubs and their break on TV.

And you ask some of the people in comedy today about the mountains, they sound pained.

“I don’t even think of it as show business,” says George Schultz, the owner of Pips in Brooklyn. “It’s an anachronism, a closed-shop kind of thing; none of these guys could go anywhere with it … go, say, on

The Tonight Show

.”

Likewise, some of the people who came out of the mountains see little of value in comedy today.

“Today everybody’s doing the same act,” says Jack Carter. “They have no performance value. In the Catskills they demanded more showmanship—to dance, to sing, to do improv….”

“You had to

give

to an audience up there,” says Joey Adams. “Woody Allen would die there…. He just hasn’t got the warmth. A Berle is a giver; a Jackie Mason is a giver….”

But you know, this is really superficial, a confusion of content and style. Woody Allen wouldn’t play in the mountains, maybe.

Maybe

. His style is more the third generation, the college-educated professional, while most of the Borscht Belt veterans were of the working class that came before. But when you look at the content of the thing, the attitude, they are not so far apart.

Jackie Mason, a brainy and traditional Borscht comic, doing his routine on the bad nerves of Jews in boats, is not so far from Woody Allen’s Broadway Danny Rose faced with a trip across the Hudson. “I don’t travel by water,” says Danny. “It’s against my religion. I’m a landlocked Hebrew.” Shtetl humor.

Jackie Mason doing his bit about the eating and drinking habits of Jewish people—“Ya see a Jew in a bar, he’s lost; ya see a Jew in a bar, he’s looking for a piece of cake”—is not so far from Allen’s hero in

Annie Hall

trembling at the sight of lobsters on the loose. “Talk to him,” Alvy says to Annie. “You speak shellfish.” And Carson, in his timing, in that look when he misses a joke, is pure Benny. And Benny, though he only played the mountains later, was Borscht. And Pryor, when he does his bit about the heart attack, when he clutches his heart and falls to the floor and starts hollering, “You didn’t think about it when you was eating all that pork,” is, in his attitude (expectant of disaster: Keep your eye on the exit), pure Borscht.

It’s style, often, that separates Allen from Mason—a figure of speech, a veneer that comes from education, a gloss. The basic attitude of Borscht Belt—which is to be an outsider with all the conflict of the outsider; which is to expect the worst because the worst is what outsiders often get; which is to be funny because funny is the only strength the powerless have—remains.

A great part of it does not translate to other cultures, is True-blue Jew, making performers fear it; but the heart of it, should you change an ethnic detail here and there, can be made universal, translating to any alienated outsider group:

Two old Polish ladies sitting on the stoop talking. “Ya see what happened with Solidarity this week?” asks one

.

“I don’t see nothing,” the other one says. “I live in the back.”

A continuum, you see. Borscht has always been a continuum; an attitude that began, most likely, when the first Jew, at about the time of the destruction of the Second Temple, looked up and said, “Y’know, I think I’m beginning to see a

pattern

….”

And if there seemed a golden time of Borscht in the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties in the Catskills, it was not because these were the decades when Borscht was invented; it was because the number of small hotels, the coming together of the comics at that time, made the mountains such a conspicuous, fertile field, a seeming mother lode.

With the disappearance of the hotels, it seems diminished. Though, if you are curious, some of the essential flavor remains. Go to Kutsher’s on a weekend: the same busboys will be hustling for tips on the floor; the same gang will be on the lawns, playing gin; the band will play the same goddamn music—“Yellow Bird,” “More,” “Matilda”—and when they play “Matilda” they will make the same (“My Zelda”) awful joke. And when the master of ceremonies, somebody’s moonlighting cousin, surely, hollers “Merengue,” the same crowd of Jews will thunder to the floor. And you, outcast hoodlum, whatever the specifics of your great sorrow, you, the next time they shout it, will get up with the people, and show your joy of the mountains, and shake it, shake it, shake it across the floor.

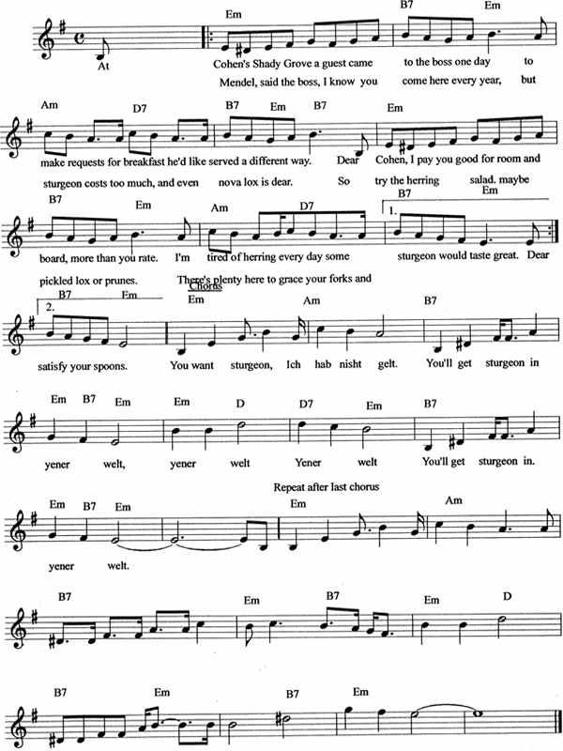

Yener Welt

At Cohen’s Shady Grove a guest came to the boss one day

To make requests for breakfast he’d like served a different way

.Dear Cohen, I pay you good for room and board, more than you rate;

I’m tired of herring every day; some sturgeon would taste great.

Dear Mendel, said the boss, I know you come here every year,

But sturgeon costs too much, and even nova lox is dear.

So try the herring salad, maybe pickled lox or prunes

There’s plenty else to grace your forks and satisfy your spoons.

You want sturgeon, ich hab nisht gelt

You’ll get sturgeon in yener welt

Yener welt, yener welt

You’ll get sturgeon in yener welt

Mister Cohen, I’d like a window station where the tips are grand

My college fees and books and things have gotten out of hand

.I’ll serve the guests with friendly smiles, a Yiddish phrase or two.

So give me this, dear Mister Cohen, I kindly ask of you.

You want a window station, but you’re slow to serve the mains;

Your shoes have drops of schav and your pants are full of stains.

You’ve got to have more class, you’ve got to have more style,

So keep your station by the kitchen door a little while.

Shine your shoes, fix your belt

You’ll get a window station in yener welt.

Yener welt, yener welt,

You’ll get a window station in yener welt.

Late August came, the guests were sparse, and Cohen let out a shriek.

My mortgage never stops for sluggish end-of-season weeks. The meat will spoil, the fish will smell, potatoes will grow eyes

How can they go to Bernstein’s Lodge or Schwartz’s Paradise?

The busboys and the waiters thought how all that season long

Cohen had served them week-old flanken, fed them for a song

They didn’t care if Shady Grove went bankrupt, broke, and dead

The dining staff stared right at Cohen, and this is what they said:

Hold your horses, tighten your belt

You’ll get more guests in yener welt.

Yener welt, yener welt,

You’ll get more guests in yener welt.

Now Cohen was not the only owner in the Catskill Mounts

And Shady Grove was not the only schlock house that we count.

Some were better, some were worse, and most were in between,

But said to say, the Mountains died, we lost the whole damned scene.

So join us as we recollect the golden years we spent

And shed a tear and give a laugh at how they paid the rent.

When people ask about the Catskills, tell them it was tops,

And lift your glass to make a toast with Mister Cohen’s schnapps.

A song you’ll sing, a tale you’ll tell

We’ll have another hotel in yener welt.

Yener welt, yener welt

We’ll have another hotel in yener welt.