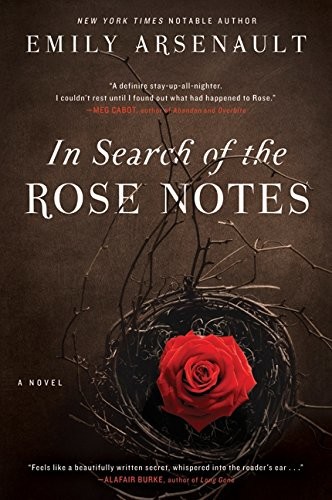

In Search of the Rose Notes

Read In Search of the Rose Notes Online

Authors: Emily Arsenault

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Mystery, #Thriller, #Adult, #Contemporary

In Search of the

ROSE NOTES

EMILY ARSENAULT

Contents

Chicago.

A man is about to get on a routine flight.

Suddenly, he pauses. He doesn’t know why—but he’s got to walk away.

An hour later the plane goes down in flames.

It’s dismissed as chance… .

—Time-Life Books commercial, circa 1987

When I was a kid, I used to stop cold whenever one of those commercials came on. If I was drowsing to my mother’s game shows, I’d jolt awake, sit up straight, and listen. If I was playing with my Spirograph on the floor, I’d stop, stare, and let my colored pen go loose in my hand. If I was getting a snack in the kitchen, I’d run back to the living room to watch. Like the Pied Piper, the spooky synthesizer music drew me in, and the stories told by the priestly sounding narrator gripped me long after the commercial was over—usually past bedtime. I’d lie awake thinking of the woman with the prophetic dream of schoolchildren dying in an avalanche. The matching drawings of aliens produced by abductees who’d never met. The man who points a clover-shaped wire at Stonehenge, feels an inexplicable surge throughout his body, then faints. And I couldn’t dismiss any of it.

There are so many hints of a world more remarkable than we ever imagined, and of abilities that we barely suspect. Send for your first volume on a trial basis and see if you can explain these things away… .

It wasn’t until we were eleven that Charlotte and I learned that her older brother, Paul, had had several of the books in his bedroom for years. All this time we’d been passing his room, holding our noses against the smell of dirty shirts and rotting dregs of milk shakes—and this treasure had been buried there. It was like finding a sacred scroll in the Dumpster behind Denny’s. Turns out he’d bought a subscription with some paper-route money but eventually canceled it when he got tired of the books, which weren’t actually that great, he said. And now he was cleaning out his bedroom, making space for a stereo he planned to buy, and was going to chuck the books if Charlotte didn’t want them.

Charlotte kept her fifteen treasured volumes at the bottom of a cardboard box in her closet, covered with a stack of

Highlights

magazines. The books were beautiful. The textured black covers with the silver lettering made them feel very official and adult, like a high-school yearbook. And the smell of the thick, glossy pages reminded me of new textbooks at school—which confirmed the seriousness of their contents. Besides, it seemed that Paul had barely cracked them. The text was difficult, but Charlotte used her top reading-group skills to decipher a few pages nearly every night. She found the most important and interesting bits for me. Plus, there were lots of pictures. Almost every day after school, we pored over the books, boring Charlotte’s beautiful teenage baby-sitter—Rose, with the dirty-blond hair and even dirtier mouth—practically to death.

But then Rose disappeared in November of our sixth-grade year, making the books even more vital to us—no longer a mere source of entertainment but an investigative guide. By then we knew better than the neighbors who whispered “runaway” and the police who let her trail go cold. We knew better than to stop at what people aren’t willing to talk about. The commercials had explained that there is much that is unknown but promised that the books would tell us at least “what could be known.” And Charlotte and I took them at their word.

Visions and Prophecies:

November 1990

After Rose disappeared, Charlotte’s parents never found a replacement baby-sitter. Either they were hoping that Rose would return any day or they’d finally figured out that Charlotte was old enough to take care of herself for a couple of hours each afternoon before Paul arrived home from soccer practice.

“I’m still worried about Rose,” Charlotte told me about a week after the disappearance had hit the news. We were sitting cross-legged on her bed, playing a halfhearted round of Rack-O.

“Everybody is,” I said.

“Her picture was in the paper again this morning.”

“I know,” I replied, a little annoyed. Sometimes Charlotte acted like I lived in a cave.

“I don’t think we should just be sitting here playing games. I think we should be helping them find her.”

I wasn’t surprised when Charlotte went to the corner of the closet where she kept her black books. Sighing, I reshuffled the Rack-O cards. I wasn’t in the mood for the black books just now. And I wasn’t sure I could handle the darkness of their contents without Rose’s sarcasm there to lighten it up.

But the picture Charlotte held out to me was a beautiful one, unlike anything she’d ever shown me in the books before. An African woman was sitting in deep orange sand, her shadow extended behind her. Before her were two long rows of flattened sand, each about three feet wide. Within each row was a symmetrical series of boxes, drawn with raised sand borders. Some of the boxes had sand symbols built in them—small spherical mounds, clusters of craters, finger-drawn horseshoes and crosses. Some boxes were left blank. Little sticks stuck out of a few spots on the grid. It looked like a hopscotch court, except more delicate, more beautiful, and far more important.

“It’s used to predict things. It’s used by a tribe in Africa called the Dogon,” Charlotte explained, pronouncing the tribe name like “doggone.” “They leave it like that at night and wait for a sand fox to come and walk over it. They read the footprints—which boxes he walks in.”

“What if a different animal comes?” I asked, not so much because I cared but because it seemed like something Rose would have said if she were around.

“I’m not sure,” Charlotte admitted. “But the sand fox is sort of magical.”

I nodded and looked back at the photo. I wished they’d also included a picture of a sand fox.

“I thought we should do one for Rose,” Charlotte said. “We should do one to help find out where Rose is.”

“Yeah,” I agreed. “That sounds good.”

“In the backyard, don’t you think? There’s the spot under the tree where the grass never grows.”

“Sure. Wherever.”

“Or in your yard, maybe?” Charlotte suggested. “There’s lots of patches that don’t have grass.”

“Mrs. Crowe would kill me, and then my mother would kill me again. Mrs. Crowe’s really weird about her yard. She has dreams about dogs in her yard and then wakes up in the morning and goes out to look for the imaginary poops she thinks they left.”

“You’re so

weird,

Nora.”

“

I’m

not. It’s

her.

” Charlotte didn’t understand the politics of living in a two-family house. She knew nothing of grumpy old landladies. “I’m not making that up.”

“We’ll do it in my yard, then.”

“It doesn’t say here what the different symbols mean.”

“We’ll have to think up our own,” Charlotte said. “Ones that say stuff about Rose.”

“And since we don’t have any sand foxes around, what do we do? Wait for a dog to come by?” I asked.

“Funny that our road’s called Fox Hill and there are no foxes around.”

“Probably there used to be foxes,” I said. “Probably they shot them all.”

“Who?” Charlotte asked, taking the book from me.

“I don’t know. The Pilgrims. The pioneers.”

“Oh. Yeah, probably. Well, I was thinking we could try to get Rose’s cat over here to walk on it. Wouldn’t that make more sense than Brownie, or just any old dog or cat? Rose’s cat probably senses things about Rose.”

“I don’t know if Rose was very close with her cat. She never talked about him.”

“Teenagers don’t talk about their pets,” Charlotte snapped at me, as if this were common knowledge. “It doesn’t mean she doesn’t love him.”

Charlotte and I bundled up and went outside to the grassless patch we’d discussed. Charlotte had brought a sketch pad for practicing symbols. She sat scribbling beneath the big maple tree while I started digging in the dirt with a garden shovel that Charlotte had found in the garage. I scratched at the ground to loosen it and in some places shoveled scoops of dirt around to even out the area.

“You can make it bigger,” Charlotte said, erasing something on her pad. “There’s hardly any grass on that side, so it doesn’t really matter if you dig into it a little.”

“Okay.”

I cleared a rectangle of about three by five feet and then split it lengthwise with a one-inch ditch. Then I joined Charlotte, sitting on the long root of the maple.

“This is what I have so far,” she said. “I think we should use the top box for ‘Where,’ the bottom one for ‘When.’ Where she is and when she’s coming back.”

“Okay.”

“And here are some of the symbols we can use.” She let me take the sketch pad from her.

I pointed at the first symbol. A rectangle with a small tail on its lower left side.

“Still in Connecticut,” Charlotte explained.

I nodded, recognizing the shape of the state. We’d had to draw it about a hundred times in fourth grade. I moved my finger to a crudely drawn airplane.

“Far away,” Charlotte said. “In a different state.”

A Saturn-like symbol. “Aliens took her. Outer space.”

I looked up. “Aliens? That’s not funny. That’s stupid.”

“The way she talked about it, I just thought we should include it.”

“Fine.”

Four vertical lines: “She’s stuck somewhere, and she’s trying to get back. The lines are like prison.”

I stiffened, trying not to picture Rose in a prison, or worse.

A stick figure with a few lines of hair flying behind, arms out. Smudged on the bottom because Charlotte had erased and redrawn the legs a few times to perfect the angles of legs in a running motion.

“She ran away,” Charlotte said.

I nodded and moved down to the “When” symbols.

A moon and sun: “Tonight.”

A cross: “Before Sunday.”

A Christmas tree: “Before Christmas.”

A small grid of squares: “Not for a long time. That’s a calendar. Many days.”

“That’s it?” I said.

“That’s all I have so far. You can add some if you want.”

I handed the pad back to her. Something was missing. I wasn’t sure if it belonged in “Where” or “When.” It would be a pretty easy symbol to do. A skull and crossbones or the horseshoe hump of a gravestone.

I stared at Charlotte. I felt nauseous, but her face showed only curiosity.

“What is it?” she said.

“But what about… ?”

Charlotte cocked her head, waiting. Maybe we just weren’t going to say it. Like when I said something especially gloomy to my mother, about rain on parades or squirrels choking on acorns or whatever it might be, and she’d say,

We’re not going to think about that, Nora.

So this was something similar. We weren’t going to think about it, and we certainly weren’t going to talk about it.

“Nothing,” I said, kneeling in the first dirt rectangle. I was grateful to have something to do to take my mind off what we weren’t going to think about. I put my hands in the dirt, smoothing it with my fingers, and then set to work. Mashing the soil together with my index fingers, I raised the frames of the first row of boxes.

May 18, 2006

Fitting that Charlotte would call while I was doing nothing. When we were kids, she was always saving me from nothing.

What are you doing? Nothing.

And compared to Charlotte’s house, with its big brother, its basketball hoop, its VCR, its trampoline, and its pantry full of Oreos, my place really was nothing.

You wanna come over?

Nothing but an apartment with neatly dusted hardwood floors, a grainy television without a cable box, a crotchety old landlady downstairs, and a single mother who prided herself on getting five meals out of a single chicken. Did I want to come over? Back then the answer was always yes.

This time when Charlotte called, I was sitting at my wheel in the garage, staring at a sketch I’d done a week earlier—of a squat teapot with a wide, round handle. I’d nearly sat down twice to make it, and twice I’d found myself distracted by something more pressing—a bill I’d forgotten to pay, the lawn I’d meant to mow.

Now I gazed at the freshly wedged lump of clay in my hands. I hadn’t much else to do but throw it down and get started. My grades were submitted, the laundry was done, and this had been my plan all along. Same as last year. Spend the summer throwing like crazy so I’d have lots to sell through Christmas, even if my teaching didn’t allow me much time at the wheel in the fall. It had worked beautifully last year. But this year I just wasn’t getting into it the way I had. Neil and I no longer really needed my meager profits from the craft fairs and farmers’ markets—and maybe I didn’t need any more compliments from hemp-skirted ladies and their gentle, bearded husbands. Not to mention that I was a little tired of my quaint teapots and teacups. While I had nothing against quaintness, I wasn’t sure I wished to generate it anymore.

I considered ignoring the phone when it rang. Clearly I was having the sort of existential moment a career in ceramics is supposed to protect you from. If I focused, if I made myself stay in the garage, I could work through it. If I simply ignored everything else and got the wheel spinning, I’d probably just forget about it.

After the third ring, I jumped up and ran for the door to the house.

“Hello?”

“Hello? Nora?” I felt oddly relieved by the sound of her voice even before I knew who it was. “It’s Charlotte Hemsworth.”

“Charlotte?” I repeated. “HEY!”

“Yeah.”

“Wow. How

are

you?

Charlotte hesitated. “Not so bad. And you? I heard you and your husband bought a house.”

“Umm, yeah.”

I looked around the living room skeptically. It had been five months since we’d painted these crisp yellow walls. Neil had assured me that we’d feel better about our color choice once we filled the living room with furniture and hung some pictures on the wall to break it up. But we’d done all that and I still wasn’t convinced.

Charlotte was silent on the other end.

“How’d you hear about the house?” I asked.

“I called your mom, and she told me. That’s how I got your number. She’s easier to find than you are. Your old number didn’t work.”

“My e-mail’s still the same, though.”

“I didn’t want to e-mail you, Nora. I wanted to talk to you.”

“Well, that’s nice. I’m glad you—”

“Nora,” she interrupted.

“Yeah?”

“They found her.”

“Found… who?”

“Rose.”

I had a flash of Rose walking into the Waverly police station, her dark blond hair still brushing her shoulders, her wide-necked purple sweatshirt still hanging off one shoulder, exposing her exotically black bra strap. Smelling of the Love’s drugstore perfume that was supposed to cover up the smell of her cigarettes. That stone-washed jean jacket tied around her waist. Her face about fifteen years older. Or—had it been more than fifteen years?

“Oh, my God,” I whispered, my heart now racing. “Is she—”

“They found her body, I mean. Bones.”

I leaned against the wall, pushing the phone so hard against my ear that it hurt.

“Nora?” Charlotte said.

I tried to picture what Charlotte might look like at this very moment. Sitting at her parents’ old kitchen table, surrounded by that ugly mauve wallpaper with the ribboned clusters of white flowers. Saying my name so gently into the phone, as if coaxing me there for another sleepover, promising no scary movies this time. A promise she never seemed to keep.

“I’m here,” I said. Sort of. “How do they know it’s her?”

“Something about a bracelet, clothing fibers… . Listen, I’m e-mailing you an article. I just didn’t want to surprise you with it.”

Listening to Charlotte, I could almost smell her mother’s Pall Malls. That kitchen was where I was supposed to be when we found Rose—not in this perky little bungalow where Neil and I had accidentally painted every room one shade too bright.

I heard Charlotte take a breath.

“Where, Charlotte?”

“I’m at home,” Charlotte said vaguely.

“No. Where did they find her?”

“Near the pond. Adams Pond.”

“But… didn’t they comb that area when we were kids? A few times, even?”

“I’m not sure. But yeah. I thought so.”

“Was she buried really deep? I mean, how did they know to dig there?”

“Nobody

knew

anything. Some kids just…

found

her. There was something sticking out of the ground, I guess, and… well, I’m not sure. My friend Porter’s done the first couple of stories for the paper, but the police aren’t giving out that many details.”

“Your friend Porter?”

“From when I worked at the

Voice,

” Charlotte said with a sigh.

“Oh,” I said.

“Of course there are all sorts of rumors. I’m not sure how accurate it is, but one scuttlebutt is that the body was moved there. Recently.”

I slid down the wall until I was sitting on the floor. “But that’s… crazy. That’s impossible.”

“I know.”

Now that I was seated, I took a deep breath and tried to get my head around it: Yes, this was real. I was talking to Charlotte again.

About Rose.

But then, what else did we have to talk about except Rose? We’d politely pretended otherwise for years, but Rose was really the only thing we could still have in common.

“Are you all right, Nora?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said.

“Are you near a computer?”

“No. Why?”

“I’m sending you the article just now.”

“You want me to read it right now?”

“Well… if you want.”

Charlotte’s sideways insistence was familiar and therefore comforting.

“Give me a few minutes,” I said. “I’ll call you back.”

I opened my laptop and found her e-mail sitting there, dated just one minute before now. The link was to an article in the

Voice.

I had no idea my old hometown paper had gone high-tech.

ADAMS POND BODY LIKELY

MISSING YOUNG WOMAN

WAVERLY—The bones found last week near Adams Pond are likely those of Waverly resident Rose Banks, who has been missing since 1990, according to police.

“It’s still quite early in the investigation, but we now believe that this could be Rose Banks. We’ve already spoken to the family, and if it is her, we hope that this will give them some closure in what has been a painful case,” Waverly police chief Carl Fisher said during a press conference yesterday.

The skeletal remains, along with Banks’s dental records, have been sent to a forensics lab in Hartford for further testing, which could take several weeks. Tolland County coroner Donald Campbell, in a preliminary investigation, identified the skeletal remains as belonging to a female between the ages of fifteen and twenty, which have been decomposing for at least ten years, Chief Fisher said.

The body was found Thursday near Adams Pond by two boys who were fishing there. Local and state police closed off the entire pond area to search for additional clues.

This discovery reopens Banks’s sixteen-year-old case, the only missing-person case ever reported in town history. Banks, age sixteen, was last seen on the evening of November 15, 1990, walking home from a baby-sitting job in her Fox Hill neighborhood. Police and town residents searched for weeks but found no clues suggesting her whereabouts.

“With the help of Detective Tracy Vaughan of the state police cold-case unit, we’re going over every detail of the case to make sure we didn’t miss anything. We’ll likely reinterview many of Miss Banks’s friends and associates, and we would be grateful to speak to anyone else who might know something about this case,” Chief Fisher said.

So it was real. They’d found Rose. After all these years. As I read the article again, I had a feeling that my wheel wouldn’t be spinning for another week at least. I knew I needed to see Charlotte, and she needed to see me.

Psychic Powers:

August 1990

It was Charlotte’s idea to make the Zener cards. Like all her projects that summer, the idea came out of the Time-Life books. We pronounced them ZEE-ner cards. Rose managed to turn the making of the cards into a two-afternoon affair—one for walking a mile and a half into town to Rite Aid for a pack of three-by-five cards, the other for carefully crayoning thick black circles, squares, crosses, stars, and (the most fun, but also the most difficult) three-lined psychedelic squiggles. Rose rejected our early attempts, insisting that the waves needed to be parallel and that sloppiness might confuse the mind and skew our results.

On the third day of the project, Rose finally shuffled the cards and laid them out for us. She’d been designated for this task since she was, for all intents and purposes, the grown-up. Charlotte and I would take turns guessing the symbols on the overturned cards and recording each other’s results. On the first try, I got ten out of twenty-five. Charlotte got four. On my second round, I noticed Rose’s face changing before some of my guesses. Her mouth opened round before a circle; her head bobbled lazily before the wavy lines. Once she was certain I’d noticed it, the gestures became subtler—a slight movement of the mouth for a circle, a twitch of the chin for the squiggles. For stars, squares, and crosses, she offered no help, keeping her face motionless and her eyes slanted toward the ceiling in an exaggerated expression of disinterest.

“Wow.” Rose raised her eyebrows at Charlotte when my second and third rounds turned out an impressive thirteen and eleven respectively.

Through Rose’s facial codes, I noticed a helpful pattern—more often than not, she put squiggly lines on the edges and circles somewhere in the center of the five-card rows. Her hints weren’t always discernible, and sometimes Charlotte’s intense gaze made it impossible to sneak a look at her. But overall the help made my results significantly higher than Charlotte’s. As my psychic superiority became apparent, Charlotte was clearly perplexed. Instead of scrutinizing us, however, she simply focused harder on her own guesses. Frowning and uncharacteristically silent, she was determined to reverse the results. She had apparently been certain that

she’d

be the psychic one. We knew this without ever hearing her say it. Whenever a situation allowed for someone to be the winner, or to be special, Charlotte inevitably—and usually effortlessly—fell into the role.

Rose and I never discussed our cheating or adjusted the methods—even when we could have, when Charlotte was in the bathroom or fetching more graham crackers out of the pantry. I never understood why we were doing it. It wasn’t to laugh at Charlotte or to trick her. I wouldn’t even say Rose liked me better than she liked Charlotte. She didn’t have enough interest in either of us to form a preference.

“Your psi seems stronger for round and wavy lines,” Charlotte observed after about three afternoons of repeated testing.

I bit my lip and looked at Rose for help.

“Probably she’s using her right brain more,” Rose said quickly.

“What does that mean?” Charlotte asked.

“I learned about it in school,” Rose explained. “The left brain is more like the science and math part. The right brain is, like, the soft stuff. Art and poetry and stuff. I’m right-brained, I think. My sister’s left-brained. Nora’s probably right-brained.”

“What do you think I am?” Charlotte wanted to know.

“I’m not sure. What do you like better, math or language arts?”

“I like both.”

“Well. Then you’re neither-brained.”

“Or both-brained,” Charlotte suggested.

Rose gathered up the cards, looking bored. “Another round?” she asked, shuffling.

“This time with Pepsi,” Charlotte suggested, and then she explained to us her latest finding in the black books. Experiments performed by J. B. Rhine in the 1930s indicated that people’s ESP and psychokinetic abilities improved after they’d drunk caffeinated sodas. After hearing this explanation, Rose let us raid Charlotte’s dad’s impressive Pepsi supply in the pantry.

“If anyone asks, I drank most of it and you guys each just had a glass,” Rose called from the living room as Charlotte and I chugged in the kitchen.

I thought I sensed in that statement Rose’s desire to have a little Pepsi herself. As Charlotte refilled my glass, I stepped tentatively into the living room to ask her if she wanted any. When I saw her slip a few cigarettes out of Charlotte’s mom’s coffee-table pack, I crept back into the kitchen for my second glass.

The Pepsi results were inconclusive. Charlotte’s performance improved slightly but remained just under chance. Mine stayed the same.

“Nora’s looks like a pretty pure power,” Rose said. “Kind of a steady, unshakable vision.”

Charlotte sucked on a lock of her reddish hair. She looked wounded, but just for a moment. When her eyes met mine, she pulled the hair out of her mouth and gave me an admiring smile.

“Yes,” she said, tucking the lock behind her ear. “It looks like it.”