In Search of the Niinja (33 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

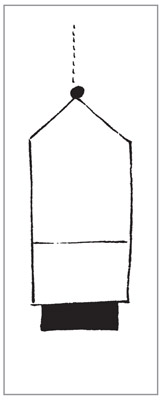

‘The Sound Amplifier’ (Courtesy of Nakashima Atsumi)

The sound amplifier taken from the

Shinobi Hiden

scroll.

A fifteenth-century German snorkel.

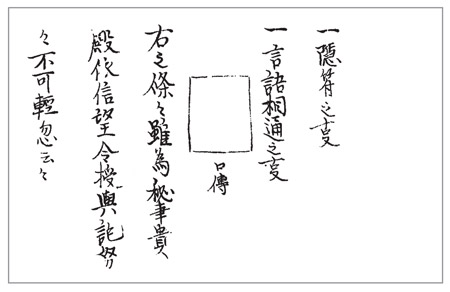

The scroll does not explain the method of secret signalling; however it talks of secret ways to communicate with conch shells, which were passed down in oral form.

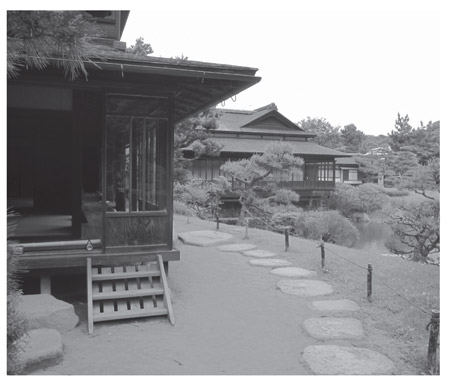

A typical Japanese compound, where a shinobi might be hiding.

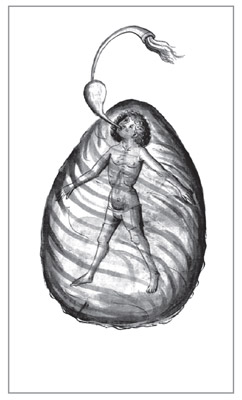

Looking at the snorkel in the

Ninpo Sho Ka-zamurai Techo

, we can see that the

shinobi

used these tools to hide in water and that snorkelling is not a modern concept. A shinobi could only move around using the snorkel if it was raining, so that it did not matter if the ninja left wet footprints. Or he could use it if spotted by the enemy by dashing into the water to hide.

Western European war manuals also contain snorkelling as can be seen in the fifteenth-century image on page 121; note the bowl to aid air intake, common with longer pipes.

It is well documented that the ninja used secret codes and hidden writings to convey messages in a warring situation. The

shinobi

also had to become proficient in the arts of signalling to the unseen. The

Bansenshukai

states that the ninja must be set up around a defensive position and that they should signal with sound and fire. Again linked to this central text, several manuals talk about the use of conch shells, bells, whistles, clappers and flutes to send messages. Of course, there was no standard message and each system had to be constructed between people, but elements such as vibrations and length of note were used to differentiate between meanings. The

Bansenshukai

even goes as far as to say a person well versed in this can hold a ‘conversation’ in much the same way as with Morse code.

A traditional gate, which a shinobi would have had to infiltrate.

The outer shutter on a Japanese window.

A Japanese locking bar.

Thatched roofs were easy targets for arson.

The shinobi would hide under bridges and listen to conversations in order to obtain information.

Notes

92

One ideogram is illegible in the text and reads ‘

Ka[?]nawa no koto

’ which leads the Team to conclude the missing ideogram is ‘

gi

’ making this ‘

Kaginawa

’ or grapple and rope.

93

Being copied does not make the manual or its information less real, and it too has its place in history, yet this needs to be before 1868 to be a form of reliable information.

94

Natori Masatake was without doubt a samurai under the rule of the Kishu-Tokugawa and Fujibayashi was most likely a

Koshi

, a form of displaced samurai, following the invasion of Iga under Oda Nobunaga.

95

Presumably this has a handle on the inside and is light weight and painted black. It would probably work extremely well.

96

Cylindrical bamboo.

97

This literally says block-wood and it is unclear if this is a tool the shinobi uses or the bar used on the door.

98

A person who is part of a group who are relatively higher ranking samurai and who are attached to divisions, literally ‘supporting groups’.

99

The same term for the same tool is used in the

Shinobi Hiden

.

100

This is most likely a reference to the blade having different size teeth on each side, according to the

Bansenshukai

one side should be a general cutter whilst the other is for bamboo.

101

Most probably a hole made by a drill.

102

The scroll in this image is not the manual quoted in the text and is in fact a different manual with this same skill, further confirming its usage across ninjutsu. As described in the other scroll, the plate under the sound amplifier can be seen. Interestingly, this scroll is signed by two ninja, Kido Hachiroemon of

Iga Otoaa

and Azumatarozaemon of

Koshu Tsuchiyama Koka

.

Ninja Magic

T

he ninja left us with only a small selection of spells from the ritual magic component of their art. The authors of the

Shoninki

and the

Bansenshukai

warn that

ninjutsu

is not ‘magic’ and is in fact a practical art, devoid of mysticism, yet both still include ritual magic. On the other hand, the Koka

ninja

named Kimura informs us that the deepest arts of ninjutsu are esoteric and ‘magical’ but become true and practical if understood. Natori Masatake also warns us not to throw away ritual magic or dismiss it, as some things do hold power. When dealing with the ninja and magic, a few considerations must be at the forefront. Firstly, ninja magic leans towards ‘psychological magic’, that is, talismans and rituals of hiding, or things that could be considered to give a ninja the psychological strength to progress. Secondly, magic was learned so that it could be used against the enemy and

his

belief in magic (Fujibayashi is clear on this point). We must remember that the ninja were from a medieval world, at a time when magic was taken for granted as a reality by many and that Japan at the time was heavily influenced by Buddhism and other creeds that were associated with esoteric magical practices. Here we encounter ‘fake ninja magic’, that is, ninja magic that was written down years later and does not comply with the feeling of the original manuals, where spells are numerous and practical ninjutsu is lacking.

103

The

Shinobi Densho

(1827) ninja scroll is concerned entirely with magic. It has reams of magical examples, some of which can be found in other ninja manuals, some of which are not, such as using the bones of rats to keep one awake for over 100 days. The authentic Koka ninja, Kimura of the Owari-Tokugawa clan, assures us that esoteric methods, such as the arts of ‘Toothpick Hiding’ or ‘Fingernail Catching’, are true and deep ninja secrets, and these do appear in the scroll.