In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind (7 page)

Read In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind Online

Authors: Eric R. Kandel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

Freud argued further that psychological determinacy—the idea that little, if anything, in one’s psychic life occurs by chance, that every psychological event is determined by an event that precedes it—is central not only to normal mental life, but also to mental illness. A neurotic symptom, no matter how strange it may seem, is not strange to the unconscious mind; it is related to other, preceding mental processes. The connection between a slip of the tongue and its cause or between a symptom and the underlying cognitive process is obscured by the operation of defenses—ubiquitous, dynamic, unconscious mental processes—resulting in a constant struggle between self-revealing and self-protective mental events. Psychoanalysis held the promise of self-understanding and even of therapeutic change based on an analysis of the unconscious motivations and defenses underlying individual actions.

What made psychoanalysis so compelling to me while I was in college was that it was at once imaginative, comprehensive, and empirically grounded—or so it appeared to my naïve mind. No other views of mental life approached psychoanalysis in scope or subtlety. Earlier psychologies were either highly speculative or very narrow.

INDEED, UNTIL THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, THE

only approaches to the mysteries of the human mind were introspective philosophical inquiries (the reflections of specially trained observers on the nature of their own patterns of thought) or the insights of great novelists, such as Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Leo Tolstoy. Those are the readings that inspired my first years at Harvard. But, as I learned from Ernst Kris, neither trained introspection nor creative insights would lead to the systematic accretion of knowledge needed for the foundation of a science of mind. That sort of foundation requires more than insight, it requires experimentation. Thus, it was the remarkable successes of experimental science in astronomy, physics, and chemistry that spurred students of mind to devise experimental methods for studying behavior.

This search began with Charles Darwin’s idea that human behavior evolved from the behavioral repertory of our animal ancestors. That idea gave rise to the notion that experimental animals could be used as models to study human behavior. The Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov and the American psychologist Edward Thorndike tested in animals an extension of the philosophical notion, first enunciated by Aristotle and later elaborated by John Locke, that we learn by associating ideas. Pavlov discovered classical conditioning, a form of learning in which an animal is taught to associate two stimuli. Thorndike discovered instrumental conditioning, a form of learning in which an animal is taught to associate a behavioral response with its consequences. These two learning processes provided the foundation for the scientific study of learning and memory not only in simple animals, but also in people. Aristotle’s and Locke’s suggestion that learning involves the association of ideas was replaced by the empirical fact that learning occurs through the association of two stimuli or a stimulus and a response.

In the course of studying classical conditioning, Pavlov discovered two nonassociative forms of learning: habituation and sensitization. In habituation and sensitization an animal learns only about the features of a single stimulus; it does not learn to associate two stimuli with each other. In habituation the animal learns to ignore a stimulus because it is trivial, whereas in sensitization it learns to attend to a stimulus because it is important.

The discoveries of Thorndike and Pavlov had an extraordinary impact on psychology, giving rise to behaviorism, the first empirical school of learning. Behaviorism held out the promise that behavior could be studied with the same rigor as the natural sciences. By the time I was at Harvard, the leading proponent of behaviorism was B. F. Skinner. I was exposed to his thinking through discussions with friends taking his courses. Skinner followed the philosophical path outlined by the founders of behaviorism. Together, they narrowed the view of behavior by insisting that a truly scientific psychology had to be restricted only to those aspects of behavior that could be publicly observed and objectively quantified. There was no room for introspection.

Consequently, Skinner and the behaviorists focused exclusively on observable behavior and excluded from their work all references to mental life and all efforts at introspection, because such things could not be observed, measured, or used to develop general rules about how people behave. Feelings, thoughts, plans, desires, motivations, and values—the internal states and personal experiences that make us human and that psychoanalysis brought to the fore—were considered inaccessible to experimental science and unnecessary for a science of behavior. The behaviorists were convinced that all of our psychological activities can be adequately explained without recourse to such mental processes.

The psychoanalysis I encountered through the Krises was worlds apart from Skinner’s behaviorism. In fact, Ernst Kris went to great pains to discuss the differences and to bridge them. He argued that part of the appeal of psychoanalysis was that, like behaviorism, it attempts to be objective, to reject conclusions drawn from introspection. Freud argued that one cannot understand one’s own unconscious processes by looking into oneself; only a trained neutral outside observer, the psychoanalyst, can discern the content of the unconscious in another person. Freud also favored observable experimental evidence, but he considered overt behavior to be simply one of several means of examining internal states, whether they be conscious or unconscious. Freud was just as interested in the internal processes that determined a person’s responses to particular stimuli as he was in the responses per se. The psychoanalysts who followed Freud argued that, by limiting the study of behavior to observable, measurable actions, behaviorists ignored the most important questions about mental processes.

My attraction to psychoanalysis was further enhanced by the facts that Freud was Viennese and Jewish and had been forced to leave Vienna. Reading his work in German awakened in me a yearning for the intellectual life I had heard about but never experienced. More important even than reading Freud were my conversations about psychoanalysis with Anna’s parents, who were extraordinarily interesting people filled with enthusiasm. Ernst Kris was already an established art historian and curator of applied art and sculpture at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna before marrying Marianne and taking up psychoanalysis. He trained, among others, the great art historian Ernst Gombrich, with whom he later collaborated, and they each contributed importantly to the development of a modern psychology of art. Marianne Kris was a distinguished psychoanalyst and teacher, as well as a wonderfully warm person. Her father was Oskar Rie, an outstanding pediatrician, Freud’s best friend, and the physician to his children. Marianne was a close friend of Freud’s highly accomplished daughter, Anna. Indeed, Marianne Kris named her daughter after Anna Freud.

Ernst and Marianne Kris were generous and encouraging to me, as they were to all of their daughter’s friends. Through my frequent interactions with them I also had occasional interactions with their colleagues the psychoanalysts Heinz Hartmann and Rudolph Lowenstein. Together, the three men had forged a new direction in psychoanalysis.

When Hartmann, Ernst Kris, and Lowenstein immigrated to the United States, they joined forces to write a series of groundbreaking papers in which they pointed out that psychoanalytic theory had placed too much emphasis on frustration and anxiety in the development of the ego, the component of the psychic apparatus that, according to Freud’s theory, is in contact with the outside world. More emphasis should be placed on normal cognitive development. To test their ideas, Ernst Kris urged empirical observations of normal child development. By bridging in this way the gap between psychoanalysis and cognitive psychology, which was just beginning to emerge in the 1950s and 1960s, he encouraged American psychoanalysis to become more empirical. Kris himself joined the faculty of the Child Study Center at Yale University and participated in their observational studies.

Listening in on these exciting discussions, I was converted to their view that psychoanalysis offered a fascinating approach, perhaps the only approach, to understanding mind. Psychoanalysis opened an unsurpassed view not only into the rational and irrational aspects of motivation and unconscious and conscious memory but also into the orderly nature of cognitive development, the development of perception and thought. This area of study began to seem much more exciting to me than European literature and intellectual history.

TO BECOME A PRACTICING PSYCHOANALYST IN THE

1950s,

IT WAS

generally considered best to go to medical school, become a physician, and then train as a psychiatrist, a course of study I had not previously considered. But Karl Vietor’s death had left an opening for two full-year courses in my schedule. So in the summer of 1951 I took, almost on impulse, the introductory course in chemistry, which was required for medical school. The idea was that I would take physics and biology in my senior year, while writing my thesis, and then, if I continued with the plan, take organic chemistry, the final requirement for medical school, after graduating from Harvard.

That summer of 1951 I shared a house with four men who became lifelong friends: Henry Nunberg, Anna’s cousin and the son of another great psychoanalyst, Herman Nunberg; Robert Goldberger; James Schwartz; and Robert Spitzer. A few months later, based on that single chemistry course and my overall college record, I was accepted at New York University Medical School, with the proviso that I complete the remaining course requirements before enrolling in the fall of 1952.

I entered medical school dedicated to becoming a psychoanalyst and stayed with that career plan through my internship and residency in psychiatry. By my senior year in medical school, however, I had become very interested in the biological basis of medical practice. I decided I had to learn something about the biology of the brain. One reason was that I had greatly enjoyed the course on the anatomy of the brain that I had taken during my second year in medical school. Louis Hausman, who taught the course, had each of us build out of colored clays a large-scale model that was four times the size of the human brain. As my classmates later described it in our yearbook, “The clay model stirred the dormant germ of creativity, and even the least sensitive among us begat a multihued brain.”

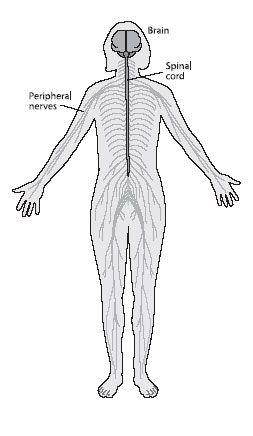

Building this model gave me my first three-dimensional view of how the spinal cord and the brain come together to make up the central nervous system (figure 3–2). I saw that the central nervous system is a bilateral, essentially symmetrical structure with distinct parts, each bearing an intriguing name, such as hypothalamus, thalamus, cerebellum, or amygdala. The spinal cord contains the machinery needed for simple reflex behaviors. Hausman pointed out that by examining the spinal cord, one can understand in microcosm the overall purpose of the central nervous system. That purpose is to receive sensory information from the skin through bundles of long nerve fibers, called axons, and to transform it into coordinated motor commands that are relayed to the muscles for action through other bundles of axons.

As the spinal cord extends upward toward the brain, it becomes the brain stem (figure 3–3), a structure that conveys sensory information to higher regions of the brain and motor commands from those regions downward to the spinal cord. The brain stem also regulates attentiveness. Above the brain stem lie the hypothalamus, the thalamus, and the cerebral hemispheres, whose surfaces are covered by a heavily wrinkled outer layer, the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is concerned with higher mental functions: perception, action, language, and planning. Three structures lie deep within it: the basal ganglia, the hippocampus, and the amygdala (figure 3–3). The basal ganglia help regulate motor performance, the hippocampus is involved with aspects of memory storage, and the amygdala coordinates autonomic and endocrine responses in the context of emotional states.

3–2 The central and peripheral nervous systems.

The central nervous system, which consists of the brain and the spinal cord, is bilaterally symmetrical. The spinal cord receives sensory information from the skin through bundles of long axons that innervate the skin. These bundles are called peripheral nerves. The spinal cord also sends motor commands to muscles through the axons of the motor neurons. These sensory receptors and motor axons are part of the peripheral nervous system.

It was hard to look at the brain, even a clay model of it, without wondering where Freud’s ego, id, and superego were located. A keen student of the anatomy of the brain, Freud had written repeatedly about the relevance of the biology of the brain to psychoanalysis. For example, in 1914 he wrote in his essay “On Narcissism”: “We must recollect that all of our provisional ideas in psychology will presumably one day be based on an organic substructure.” In 1920 Freud again noted, in

Beyond the Pleasure Principle: