In Maremma (10 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

Â

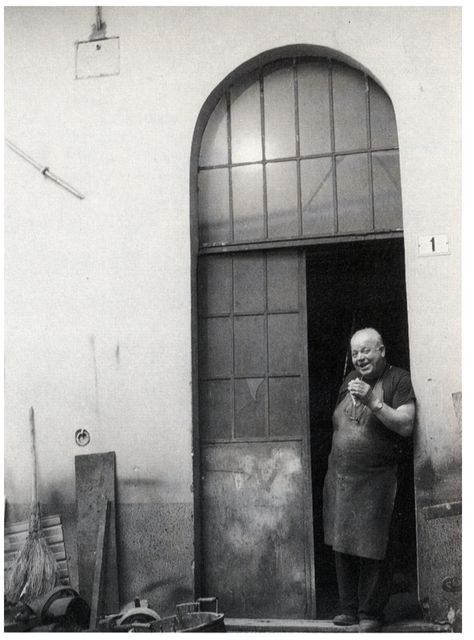

Mauro, the Ironmonger in Semproniano

(

from Samprugnano 1900â1963: Storie e Figure

)

(

from Samprugnano 1900â1963: Storie e Figure

)

Despite occasional efforts at codification,

acqua cotta

remained, in our part of Tuscany, the subject of endless, if good-hearted, argumentâmuch as in Amatrice people argued about whether a true

Amatriciana

was made with or without white wine, with

bucatini

or spaghetti. Thus while waiting in line at the butcher shop one morning, our request of the five women present for the “authentic” recipe for

acqua cotta

led to our being given five different “authentic” recipes. Sauro's sister, the cook at the old-folks' home in Semproniano, prepared a

bizarre version of this soup that, baked in a Teflon dish, resembled more than anything a Thanksgiving dressing. (In fact, you had to eat her

acqua cotta

with a fork, which was plain wrong.) The extremely refined version that Pina made at her restaurant showed fidelity to the spirit rather than the letter of the soup, for she omitted the most essential ingredients, onion and celery, in favor of a nest of spinach laid in the broth and topped with a poached quail egg. According to Pina,

acqua cotta

was eaten all over Central Italy. In her authoritative collection of regional Italian recipes, on the other hand, Anna Gosetti della Salda firmly identifies Grosseto as the birthplace of

acqua cotta

.

Her

recipe is essentially one for mushroom soup. Ada Boni's version of

acqua cotta

âwhich she gives as one word,

acquacotta

âis essentially one for bell pepper soup.

acqua cotta

remained, in our part of Tuscany, the subject of endless, if good-hearted, argumentâmuch as in Amatrice people argued about whether a true

Amatriciana

was made with or without white wine, with

bucatini

or spaghetti. Thus while waiting in line at the butcher shop one morning, our request of the five women present for the “authentic” recipe for

acqua cotta

led to our being given five different “authentic” recipes. Sauro's sister, the cook at the old-folks' home in Semproniano, prepared a

bizarre version of this soup that, baked in a Teflon dish, resembled more than anything a Thanksgiving dressing. (In fact, you had to eat her

acqua cotta

with a fork, which was plain wrong.) The extremely refined version that Pina made at her restaurant showed fidelity to the spirit rather than the letter of the soup, for she omitted the most essential ingredients, onion and celery, in favor of a nest of spinach laid in the broth and topped with a poached quail egg. According to Pina,

acqua cotta

was eaten all over Central Italy. In her authoritative collection of regional Italian recipes, on the other hand, Anna Gosetti della Salda firmly identifies Grosseto as the birthplace of

acqua cotta

.

Her

recipe is essentially one for mushroom soup. Ada Boni's version of

acqua cotta

âwhich she gives as one word,

acquacotta

âis essentially one for bell pepper soup.

In the end, like its Emilian cousin, the famed

ragú

that in Bologna is served over tagliatelle,

acqua cotta

exists more as an ideal than a rigid recipe, as essential a piece of Maremman folklore as the

butteri.

And yet ...

se c'era

... How far we'd come from Mauro's poor childhood, from those days when there wasn't enough flour, and pasta had to be made from ground chestnuts!

ragú

that in Bologna is served over tagliatelle,

acqua cotta

exists more as an ideal than a rigid recipe, as essential a piece of Maremman folklore as the

butteri.

And yet ...

se c'era

... How far we'd come from Mauro's poor childhood, from those days when there wasn't enough flour, and pasta had to be made from ground chestnuts!

17

D

URING OUR FIRST months in Semproniano, we were often asked if we were German. This was an understandable mistake: most of the foreigners who settled in this part of Italy were German. In reply, we would explain that we were Americans, at which point, inevitably, we would be asked if we came from ... where? It sounded like

airshay.

The town in question was Hershey, Pennsylvania, to which vast numbers of Sempronianini (among other Maremmani) had emigrated. Alfred Pel-ligrini: “After visiting Pitigliano, the hometown of their grandparents, friends from Hershey ... commented, âthe only difference between visiting the Italian section of the Hershey cemetery and visiting the cemetery in Pitigliano was that we couldn't smell the aroma of chocolate in Pitigliano.' The names on the headstones were the same in both towns.”

URING OUR FIRST months in Semproniano, we were often asked if we were German. This was an understandable mistake: most of the foreigners who settled in this part of Italy were German. In reply, we would explain that we were Americans, at which point, inevitably, we would be asked if we came from ... where? It sounded like

airshay.

The town in question was Hershey, Pennsylvania, to which vast numbers of Sempronianini (among other Maremmani) had emigrated. Alfred Pel-ligrini: “After visiting Pitigliano, the hometown of their grandparents, friends from Hershey ... commented, âthe only difference between visiting the Italian section of the Hershey cemetery and visiting the cemetery in Pitigliano was that we couldn't smell the aroma of chocolate in Pitigliano.' The names on the headstones were the same in both towns.”

That neither of us had ever been to Hershey surprised some of the older residents of Semproniano, for whom Hershey

was

“America.” At first the Sempronianini had gone to work in the city's quarries; later, these immigrants built the chocolate factory that would employ more immigrants. Soon Hershey became known in Tuscany as the Perugia of America. And the Hershey connection persisted. Rosaria recalled that her grand-mother,

who worked at the chocolate factory, used to return every few years bearing an umbrella filled with Hershey's Kisses. It was the shape of the sweet that impressed Rosaria when she was a girl, not the taste; at Signora Idia's

gelateria,

after all, you could get chocolate ice cream made with unpasteurized sheep's milk. “So rich! Of course you can't make it now. The law.” As a doctor, she had to approve of such regulationsâand yet: “You should have tasted it. So

cremoso

. Really, you haven't tasted ice cream at all until you've tasted ice cream made from unpasteurized sheep's milk.”

was

“America.” At first the Sempronianini had gone to work in the city's quarries; later, these immigrants built the chocolate factory that would employ more immigrants. Soon Hershey became known in Tuscany as the Perugia of America. And the Hershey connection persisted. Rosaria recalled that her grand-mother,

who worked at the chocolate factory, used to return every few years bearing an umbrella filled with Hershey's Kisses. It was the shape of the sweet that impressed Rosaria when she was a girl, not the taste; at Signora Idia's

gelateria,

after all, you could get chocolate ice cream made with unpasteurized sheep's milk. “So rich! Of course you can't make it now. The law.” As a doctor, she had to approve of such regulationsâand yet: “You should have tasted it. So

cremoso

. Really, you haven't tasted ice cream at all until you've tasted ice cream made from unpasteurized sheep's milk.”

Â

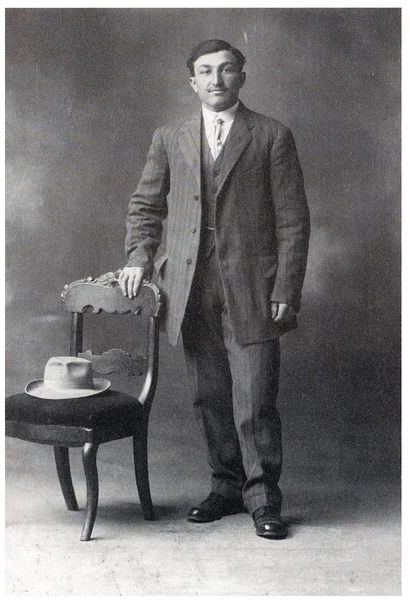

Sempronianino in Hershey, Pennsylvania

(from

Samprugnano 1900â1963: Storie e Figure

)

(from

Samprugnano 1900â1963: Storie e Figure

)

One year Alfred Pellegrini, the son of Maremman immigrants and the owner of Alfred's Victorian Restaurant in Middletown, Pennsylvania, led a tour of Hersheyites to Semproniano. They took cooking lessons at the Locanda la Pieve and ate every night at a different restaurant. The tour concluded with a dinner at Pina's, which we witnessed from our usual table by the fireplace. As each course was brought to the table, Pina would describe it to Mr. Pellegrini, who would then translate, for although most of their parents and grandparents came from Tuscany, few of them spoke Italian.

When the

acqua cotta

arrived, Mr. Pellegrini entered into a reverie about his grandmother, who had become angry at him when he had written in his cookbook that as a child he had always hated

acqua cotta.

The memory of his grandmother evidently touched Mr. Pellegrini deeply, for as he spoke of her his eyes grew moist. Pina, meanwhile, not realizing that his speech had long since moved beyond matters of gastronomy, kept interrupting to remind him that the spinach was organic.

acqua cotta

arrived, Mr. Pellegrini entered into a reverie about his grandmother, who had become angry at him when he had written in his cookbook that as a child he had always hated

acqua cotta.

The memory of his grandmother evidently touched Mr. Pellegrini deeply, for as he spoke of her his eyes grew moist. Pina, meanwhile, not realizing that his speech had long since moved beyond matters of gastronomy, kept interrupting to remind him that the spinach was organic.

Another incident stays with us. Although Giampaolo's father was the concertmaster of one of the orchestras of RAI (Radio Audizioni Italiane), his and Pina's own musical tastes ran to jazz and sometimes reggae. After a couple of hours of Bud Powell, the people from Hershey indicated that they wanted Italian music for their last night. “Dean Martin!” an older member of the group shouted hopefully, which led Giampaolo to pull out the olive crate in which he kept his cassettes. With assistance from a few of the women, he sifted through them.

“Any Caruso?”

“âO Sole Mio'?”

“How about âThat's Amore'?”

“Who's Bob Marley?” one of the women asked, picking up a cassette.

“A rap singer,” answered her friend, who was wearing a brown cloche.

Giampaolo continued to sift. Maurizio Pollini playing the Chopin études, Victor de Sabata, Buddy Holly . . . It turned out that he did not own a single tape of Italian songs.

That same weekendâit was the beginning of porcini mushroom seasonâwe went back to Il Mulino for Sunday lunch. At a nearby table sat four American men who, as it turned out, were also from Hershey, although not affiliated with the group from two nights before. After we helped translate Pina's recitation of her menu, we got to talking with them: they were on a tour of Italy in search of relatives. Only after lunch was over did we exchange names. “Scott Reese;” one of them said, holding out his hand.

“Reese as in the Reese's Peanut Butter Cup?” we queried.

His grandfather had invented it.

Later, we shared the story with various friends in SempronianoâAldo and Gianni, Pina and Giampaoloâand were surprised at how little it impressed them. For example, although Aldo stocked Kit Kat bars and M&M's, he had never heard of the Reese's Peanut Butter Cup. In any case, as we soon learnedâand notwithstanding their acute devotion to Nutella, that chocolate and hazelnut paste that European children spread on their breakfast toastâmost Italians disdain peanut butter on the grounds that it is bad for the liver. (Just as

Americans are obsessed with their hearts, Italians worry endlessly about their livers.) Even more inconceivable, to our friends, was the idea of peanut butter as a sweet, to be combined with chocolate!

Americans are obsessed with their hearts, Italians worry endlessly about their livers.) Even more inconceivable, to our friends, was the idea of peanut butter as a sweet, to be combined with chocolate!

A few weeks later, when we returned from a trip to America, we brought a box of Reese's Peanut Butter Cups with us.

“Il signore

who ate here, the one called Reese? This is what his

nonno

invented,” we told Pina, who eagerly sampled one. “Well?” we asked.

“Il signore

who ate here, the one called Reese? This is what his

nonno

invented,” we told Pina, who eagerly sampled one. “Well?” we asked.

“Discreta . . . ma non mi stupisce”

(“Not bad . . . but nothing to write home about”).

(“Not bad . . . but nothing to write home about”).

This meant we got to keep the rest for ourselves.

18

A

STUBBORN LONGING for familiar thingsâeven things at which, back home, one turned up one's noseâbecame, with the passage of years, a distinguishing feature of expatriate life.

STUBBORN LONGING for familiar thingsâeven things at which, back home, one turned up one's noseâbecame, with the passage of years, a distinguishing feature of expatriate life.

During DL's twelfth summer, he and his mother discovered from a cooking show called

The Romagno-lis' Table

that pasta could be served with a sauce that wasn't red. The recipe in question was for

spaghetti alla carbonara,

and the next evening, with a sense of adventure, they prepared some. Of course they had to approximate: instead of pancetta or

guanciale,

it was salt pork, Creamette spaghetti, and “Parmesan cheese” from a green cardboard shaker. The olive oil was a pallid yellow and came from Spainâor was it Greece? Even so, as they ate that first carbonara, it seemed to them for an instant that they could hear the Tiber flowing outside their kitchen window.

The Romagno-lis' Table

that pasta could be served with a sauce that wasn't red. The recipe in question was for

spaghetti alla carbonara,

and the next evening, with a sense of adventure, they prepared some. Of course they had to approximate: instead of pancetta or

guanciale,

it was salt pork, Creamette spaghetti, and “Parmesan cheese” from a green cardboard shaker. The olive oil was a pallid yellow and came from Spainâor was it Greece? Even so, as they ate that first carbonara, it seemed to them for an instant that they could hear the Tiber flowing outside their kitchen window.

When we first arrived in Italy, naturally, we disdained anything that tasted too much of America, exulting instead in the Italian-ness of the things we found at the grocery store: peppery olive oil, Parma ham, wheels of pecorino cheese that the

salumiere

cut with a wire. Though rarities in America at that time, in Italy such foods were ordinary; you could take them for granted.

salumiere

cut with a wire. Though rarities in America at that time, in Italy such foods were ordinary; you could take them for granted.

In those early days every trip to the grocery store, especially a stroll down the pasta aisle, sent us into a rapture. We studied the classics of Italian cookingâAda Boni and Pellegrino Artusiâin the hope of learning how to make every dish we prepared rigorously authentic. Italian cooking, a poet friend had told us, requires above all obedience to the rules; we offered out obedience and as a result became proficient cooks. Soon we could make

ragú alla bolognese

the way the Bolognese do, and

arista di maiale

the way the Tuscans do, and

spaghetti alla carbonara

the way the Romans do (as opposed to the way DL's mother had had to do). Soon wonderful food became something we felt we could count on (a very Italian attitude). And then, one morning, about three years later, we woke up wanting . . . peanut butter. So we went out and bought some (a Dutch brand) and for a few days ate little else besides peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches for lunch.

ragú alla bolognese

the way the Bolognese do, and

arista di maiale

the way the Tuscans do, and

spaghetti alla carbonara

the way the Romans do (as opposed to the way DL's mother had had to do). Soon wonderful food became something we felt we could count on (a very Italian attitude). And then, one morning, about three years later, we woke up wanting . . . peanut butter. So we went out and bought some (a Dutch brand) and for a few days ate little else besides peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches for lunch.

In this way it began. We questioned other Americans and discovered that they, too, often fell prey to culinary nostalgia. On visits home we lorded our superior knowledge of Italian cooking over our friends and families, even corrected their errors. (“No, you never put Parmesan cheese on mushrooms!”) In Italy, we stole shamefacedly into the McDonald's on Piazza di Spagna to savor a Big Mac in an invisible corner, and as often as not ran in to the director of the American Academy on the way out.

Other books

Stars So Sweet by Tara Dairman

Love Play by Rosemary Rogers by Unknown

Set This House in Order by Matt Ruff

Chaos Bound by Sarah Castille

Far From The Sea We Know by Frank Sheldon

The Deepest Ocean (Eden Series) by Marian Perera

Kaleidoscope by Ashley, Kristen

COYOTE SAVAGE by NORRIS, KRIS

Sunrises to Santiago: Searching for Purpose on the Camino de Santiago by Gabriel Schirm

Autumn Moon by Jan DeLima