Improving Your Memory (2 page)

Read Improving Your Memory Online

Authors: Janet Fogler

• What happened an hour ago

• Where you spent last Thanksgiving

• The information needed to drive a car

• The smell of baking cookies

• An image of your high school math teacher

• The multiplication tables

• A song from the 1980s

Thus, long-term memory refers to any information that is no longer in conscious thought but is stored for possible recollection.

Here are two examples of how the memory process works in daily life.

EXAMPLES

You are doing your weekly shopping at the local grocery store. There are many items on the shelves that make sensory impressions on you. You see the colors of the packages, smell the bakery products, and hear the many sounds around you. These sensory impressions, however, may or may not register in conscious thought.

You pause in the produce department and consider what fruit to serve in a salad. You glance at a papaya, a fruit you have never tried, and notice that it is very expensive. If you then move on, you will probably not recall the papaya in any detail. The impression of the papaya has entered working memory (conscious thought) but has not necessarily been stored in long-term memory.

If you pay more attention to the papaya, however, by noting its shape, color, and texture, smelling its fragrance, feeling its ripeness, and even thinking about what it might taste like or how you could prepare it, the image and knowledge of that fruit will probably be transferred into long-term memory. This information will be available for retrieval in the future, for example, when you see a recipe that includes papaya as an ingredient.

A MODEL FOR HOW MEMORY WORKS

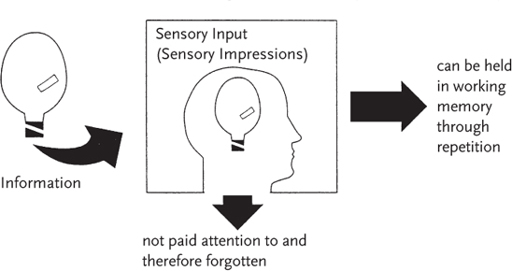

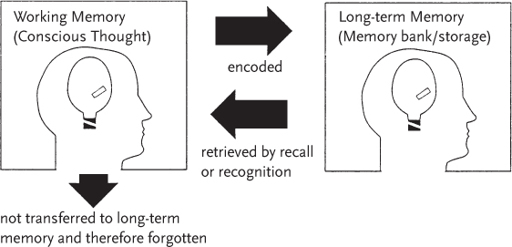

The flow of information through the three components of memory

You are addressing envelopes announcing a shower for your niece. You have a list of names but no home addresses. Your task is to look up the addresses and transfer the names and addresses to the envelopes. As you handle the phone book, your senses take in the feel of the book, the pattern of the names on a given page, and the sound of pages turning (or the feel of the pages in your hand). These sensory impressions may or may not register in working memory.

You find Laura Adam’s name and copy her address to an envelope: 4276 Woodlawn St., Chelsea, Michigan. This information has entered working memory. You hold it in your mind for the few seconds needed to address the envelope. If you are not familiar with this street, you are unlikely to store this information in long-term memory. After a few moments, you probably won’t even remember the name of the street.

If you note that Woodlawn Street is in your son’s neighborhood, however, and wonder whether your son knows Laura, you are more likely to transfer the information to long-term memory and think of her as you drive down Woodlawn on the way to your son’s house.

Even though we have presented the components of memory as if new information always flows from sensory memory to working memory to long-term memory, it is possible for information that has not registered in conscious thought to be stored in long-term memory. In certain situations you may remember things without realizing that they have entered your awareness. For example, you may not be consciously aware of all of the people sitting in the doctor’s waiting room with you, but when a man comes in and asks if you have seen a woman

in a wheelchair, you recall that the nurse took a woman in a wheelchair into an exam room.

Now that you have learned about the components of memory, you have a framework for recognizing why you may remember or forget certain things. Throughout the book, additional information—such as factors that affect memory and techniques to improve memory—will be related to this chapter’s description of the components of the memory process.

3

How We Remember

To observe attentively is to remember distinctly.

—Edgar Allan Poe

Although we may be frustrated when we forget, the truly remarkable aspect of memory is the vast amount of information we are able to store and recall. When a classmate at a reunion asks a question like “Do you remember the day John Arbec got lost at the science museum?” most of us are, in fact, able to remember that incident!

Remembering depends on learning and storing information so that it can be retrieved at some future time. Thus, successful remembering requires two things:

1. Getting information solidly into long-term memory (we call this “encoding”) and

2. Bringing needed information from long-term memory into working memory (we call this “retrieval”).

Let’s discuss what is involved in these two aspects of memory.

Encoding

The term “encoding” describes the process of getting information into long-term memory. Encoding consists of mental tasks, such as the following:

• Paying attention to something,

• Associating it with something already known,

• Analyzing the information for meaning, and

• Elaborating on the details.

Often these tasks are performed automatically, without any conscious effort on our part. These tasks give deeper meaning to the information and strengthen our chances of remembering it. Perhaps the easiest way to understand encoding is to look at how it works in everyday life.

EXAMPLE

Grant and Amy took a trip to Northern Michigan in 2010. During the weeklong vacation, they visited several beaches along the shore of Lake Michigan. On the most beautiful afternoon, they took a long walk along a deserted stretch of beach near Harbor Bay. They noticed that the rocky shoreline included multicolored pebbles and stones of all sizes worn perfectly smooth by the movement of the waves. They were amazed by the variety and number. This area was definitely different from the other beaches they had explored. They wondered what natural phenomenon had gifted this area with such beautiful stones. They collected some small stones to take home as souvenirs. They felt especially close to each other and to nature and went to their hotel feeling tired and content. Whenever they talk about this trip, they recall this day on the beach with great clarity. These memories are particularly strong, because they were encoded well and had both intellectual and emotional meaning.

Two tasks of encoding—attention and association—deserve some additional emphasis.

Attention

Remember when your mother used to tell you to “pay attention.” She was right! Paying attention—the first step in the process of encoding information into long-term memory—is one of the tasks of working memory. At any moment, many pieces of information are competing for the attention of your working memory. You may need to make a conscious effort to focus your attention on what you want to remember. Keep in mind that the amount of material you can hold in your working memory is limited. You need to zero in on what is important. The following examples may remind you of a time when your attention wasn’t focused properly.

EXAMPLES

A friend tells you to meet her for lunch at 12:00, and you make a note of the date, time, and place. You mistakenly arrive at the restaurant at 12:30 because you didn’t pay attention when the time was discussed, and you wrote it down incorrectly. Next time, resolve to focus your attention on the details of time and place, repeat them out loud, and be sure you write them down correctly.

You were given directions to a new dentist’s office, followed them carefully, and had no trouble finding it the first time. At the next visit, you assume that you will remember where to go. As you approach the area, you are confused about which high-rise building the office is in. You realize that you didn’t pay enough attention to the location and the appearance of the building the first time. In the future, note some landmarks and descriptive features that will help you tell the buildings apart.

In both of these examples, you believed that you were paying enough attention to encode the information sufficiently, but clearly you weren’t. Everyone has had this experience many times. We give superficial attention to a piece of information and then are frustrated when we can’t remember it exactly. One of the simplest ways to improve your memory is to realize the importance of focusing your attention on what you really want to remember.

Since there are often many pieces of information competing for your attention, you may find that you have paid attention to the wrong thing and have missed what you really wanted to remember. For example, you’re attending classes on memory improvement. All of a sudden, you realize that you’ve been staring at a woman’s unusual clothing instead of paying attention to the teacher. The next day you can still recall the intricate beading on the woman’s jacket but have no idea what to do for homework. In the future, when you forget something you wanted to remember, ask yourself if the problem was inadequate attention.

Association

Another aspect of encoding that deserves some explanation is association. Whether we are aware of it or not, new information is encoded by connecting it with other well-known and relevant information that already resides in long-term memory. This process is called “association.” The easiest way

to understand the concept of association is to look at how it happens effortlessly in daily life.

EXAMPLES

If you meet a new person, your memory of him may be encoded by making different associations. A friend introduced you at the theater, and you noticed his beautiful curly hair. He told you that he lives in Brooklyn and is a nurse. Thus, you could have made an association with these different classifications: curly-haired people, the theater where you met, other people who live in Brooklyn, the nursing profession, the woman who introduced him to you. In the future, thinking of any of these categories could trigger a recollection of your new acquaintance. When you see another curly-haired person or a nurse or go to the theater where you met, the experience may serve as a cue and you may think of the curly-haired nurse from Brooklyn. Although you made no effort to remember this person, your mind has made these associations on your behalf. Thanks, mind!

Suppose your granddaughter has recently been chosen to be on the high school field hockey team. You don’t know anything about how the game is played or the equipment that’s used, but you do know a lot about football. When your granddaughter explains the game and equipment to you, you automatically associate the new information about field size, scoring, timekeeping, and protective equipment with what you already know about football. Without any such associations, information about field hockey would be more difficult to encode. The next time you watch football on TV, you may think of your conversation with your granddaughter and remember that she has a field hockey game coming up.

Much association of new information is done unconsciously, but you can make a conscious effort to associate something you want to remember with something you already know. The more effort you put into creating these associations and the greater the number of cross-references available, the more likely you are to recall at will. Here are two examples of people who have made a conscious effort to associate something they want to remember with something they know well.

EXAMPLES

Amir’s granddaughter is fascinated by the children’s TV show

Sesame Street

. He recently bought a book about many of the Sesame Street characters. When she points to each character, wanting to know the name, Amir wants to be able to answer. He finds it difficult to differentiate between Bert and Ernie, two characters who are always seen together. In looking for ways to associate the names with the characters, he notices that Bert has a much bigger head. He thinks, “Bert—big! Both words begin with B. That’s how I’ll remember.”