Importing Diversity: Inside Japan's JET Program (41 page)

Read Importing Diversity: Inside Japan's JET Program Online

Authors: David L. McConnell

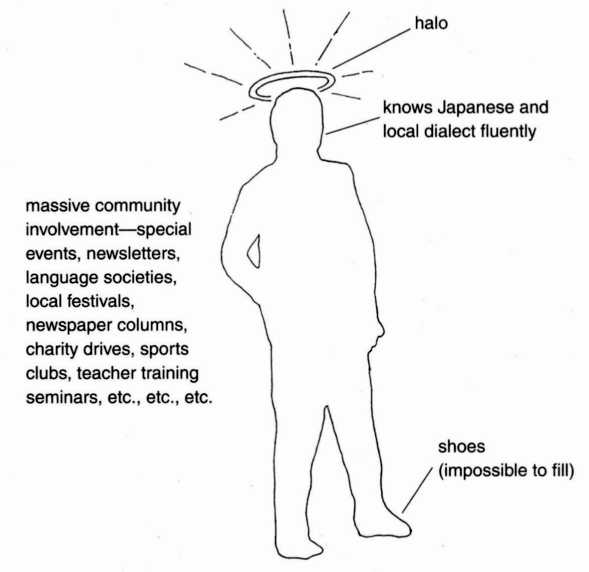

The Predecessor (Homo sapiens saintly). Distinctive call (about him or her):

"X sensei was not as [pick one] fat/short/skinny/loud/sloppy/quiet/hard to

understand/lazy as you are."

On the afternoon of the festival, most of the foreign guests were met at

the train station by pairs of students, who accompanied them on the short

walk to the school. Many of these students said that they had stayed up

late the night before rehearsing short conversational phrases that might

come in handy. On arriving at the school, all the guests were ushered into

the guest room, where forty-five foreigners were briefed on the agenda of

the afternoon. Though I had asked to sit in the background as an observer, it soon became clear that this would not do at all. The only place for foreigners here was on the stage or in designated seats-including the two

AFS students at the school, in spite of their protests that they didn't want

to be singled out from their classmates.

At the appropriate time all of the foreigners, myself included, were

given flags of our respective countries and, with the flags displayed conspicuously in front of us, we were ushered into the gymnasium. There, in

front of video cameras and to a standing ovation from the students, we

marched down a carpeted aisle to the front of the gym, where some took

seats under an impressive display of flags, banners, and ribbons hanging on

the stage, while others sat in chairs set apart in the audience. On the stage,

vases of flowers adorned tables with white cloths; the names and countries

of origin of those seated behind them were displayed prominently on large

cards.

The program had been meticulously planned down to the last minute,

and a full rehearsal had taken place the day before. A young JTL with good

conversational ability served as moderator. First, the principal gave an introduction in Japanese and in English, reading phonetically. (The speech

had been written and translated by a JTL, and the principal had received

coaching, I was told.) Then greetings were heard from a representative of

the foreigners and from the student body president, who gave his short remarks in Japanese, English, French, and German. Next, the chief organizer

of the event welcomed everyone and pointed out that there were over forty

people representing twenty-three countries, making this the biggest such

festival yet. As she went on to introduce everyone by name, students

brought leis made of folded origami cranes, which they placed over each individual's neck. The moderator then noted that since there was not enough

time to hear from all the foreigners, they would hear from just a few representatives. During the next twenty minutes, the students heard brief

greetings and introductions about their countries from a Tanzanian, a

Canadian, an Austrian, and a Korean. By my rough estimate, about a third

of the students were dozing during this portion, another third were talking

quietly among themselves, and the final third were quite attentive.

The next portion of the ceremony was titled "Question and Answer

Session," and the moderator announced that the students would take

charge of the program from here on out. The students designated as "question askers," all seated together, rose one by one and asked a question in

English of someone on the stage. I was told later that deciding on what

kinds of questions to ask was very difficult for the students, and that the

organizer had told them to keep to noncontroversial subjects that would contribute to a light atmosphere. Indeed, the nine questions addressed topics such as fjords in Norway, clothing styles in Sweden, vacation time in

Britain, foods in Singapore, seasons in New Zealand, festivals in Brazil, and

so on. Immediately after this, two students grabbed the microphone and

walked down the row of foreigners; all were asked their country's name

and to say "konnichiwa" (hello) in their native language. Then the student

body president did the same for the foreigners seated on the stage, but he

made everyone laugh by telling the audience "Repeat after me!" after the

words in languages such as Swahili that were not familiar. The final event

had the two AFS students at the school come up and show their version of

"rock, scissors, paper" (a popular way of making decisions among Japanese

schoolchildren) in which the loser had to do whatever the winner asked.

First, the boy lost and the girl asked him to do ten push-ups on the stage;

then the girl lost and the boy asked her to kiss him on the cheek, which she

did, pretending to be embarrassed. Everyone in the audience gasped. The

two told me afterward that they had decided to do this at the last minute to

"stir things up a little."

At this point, the ceremony was declared over and, to applause, the foreigners paraded out. Their departure marked the end of the required portion of the event for ninth graders, who were then dismissed to study for

exams. Volunteers from the seventh and eighth grades were responsible for

small "discussion forums" held in various classrooms. Most of this time

was spent playing a language game and sharing snacks and tea. Depending

on the mixture of students and the personalities of the foreigners, the atmosphere ranged from quite lively and fun to somewhat uncomfortable.

At the end, the principal and the chief organizer suddenly burst into each

room with a photographer, who snapped several poses of all of us (these

pictures were later sent to all the foreign guests). The foreigners were then

ushered back to the guest room, where we were given pottery bowls as a

gift and bade farewell until the following year.

Less than a month after attending the high school festival I was invited

to an "international understanding period" at a junior high school that the

city board of education had designated a special school for returnee children. Each year this school conducted a schoolwide international event. According to a memo prepared by the planning committee,

Last year, under the title "interacting with exchange students"

(ryugakusei to no fureai no kai) we tried to improve students' interest

and understanding of intercultural differences by hearing from foreigners currently living in Japan. This year we have planned a program according to grade level under the general theme "the capacity for

cross-cultural understanding" (ibunka rikai noryoku). We want to impress on students that there are many people in the world who live and

behave in ways that differ from their own lifestyles, and we want them

to learn to respect these various moral frameworks. We also hope to encourage them to think about the question of how Japanese should conduct themselves in order to get along with people around the world.

As in the high school festival, there was an emphasis on form and careful

attention to detail. A specific activity had been designed for each grade: seventh graders were to "learn about differences between Japan and foreign

countries" by listening to three foreigners briefly describe life in their

countries. The eighth graders were to participate in a symposium on "Japanese patterns of behavior." The ninth graders were to listen to two Japanese overseas volunteers tell of their experiences, the theme being "Japanese actively participating in the world community."

I attended the symposium, which involved a panel discussion with one

foreign guest, one Japanese teacher, one moderator (also a teacher), and

seven students (one representative from each homeroom), all of whom sat

on the stage in the gymnasium. The remaining three hundred students sat

in straight lines on the floor of the gym while the physical education

teacher and several homeroom teachers roamed about, keeping strict order.

The questions chosen for discussion were most revealing. There were

twenty of them, all based on the pattern "Why do Japanese do such-andsuch?" (naze nihonjin wa ... na no ka?). These questions had been compiled by a social studies teacher in collaboration with a few of the returnee

children at the school. For nearly forty-five minutes the panel discussed

such questions as, Why are parking violations so frequent in Japan? Why

don't Japanese buy groceries all at one time? Why has Japanese science not

advanced relative to other countries? Why do so many Japanese wear

glasses? Why do Japanese work too hard? The student representatives had

all prepared written responses, and the moderator moved back and forth

between the students, the foreign guest, and the Japanese teacher, calling

for comments at random. Toward the end of the hour the moderator tried

to elicit responses from some of the students in the audience, with limited

success, by asking their opinions about a neighboring city's decision to require students to cut their hair a certain length.

These two festivals offer many insights into the cultural form and

meaning of internationalization in Japan. We might observe first that the

main event was compulsory for all students. In effect, the decision that it is important to be international was made for the students. One major consequence was that the entire event was standardized and ritualized. The Japanese attention to form, detail, and protocol in implementing this festival

clashed with the sensibilities of many of the foreign participants, as the improvisation by the AFS students revealed. As Takie Lebra has pointed out,

face is most vulnerable in unpredictable situations, and ritual-"the rigid,

meticulous control of interaction behavior in a predetermined way so as to

prevent embarrassing surprises"-is the most common means of preserving it.19 Ritualization can thus be seen as a way to control foreigners, incorporating them while forestalling any challenge to local meanings.

At both events the distinctions between Japanese and non-Japanese

were assumed and reinforced. The students who participated in "internationalization" by watching forty-five foreigners paraded in front of them

learned firsthand that foreigners were to be treated differently from themselves. The second event is a bit more complicated to analyze, for my discussions with teachers afterward made clear that the entire affair was intended as an internal critique of Japanese behavior. Yet the critique itself

began from a presupposition of Japan's cultural uniqueness, which was assumed to pervade even such things as how Japanese do their shopping. The

potential for effective criticism was further weakened by the assumption

that all Japanese are alike (are there no Japanese who do not work hard?),

behaving in ways juxtaposed to an implied and equally monolithic set of

"foreign" cultures.

THE CULTURE AND POLITICS OF TEAM TEACHING

Even more useful than school-based international festivals as a lens on the

dynamics of intercultural encounters in the JET Program were the teamtaught classes conducted daily by ALTs and JTLs. My first introduction to

the controversy over team teaching came when I attended a fall 1988 meeting of a local chapter of Nihon Eigo Gakkai (the Japan English Association),

a national organization for Japanese teachers of English. According to its

chair, the main purpose of the meeting was to help JTLs who were having

trouble (kuro) with team teaching, and three speakers talked at length

about their personal experiences with ALTs. While the Ministry of Education's main speaker at the JET Program orientation had glowingly reported

that 75 percent of JTLs were very positive about team teaching, this session

painted a much bleaker picture. Even the moderator's introductory remarks about the JET Program were decidedly negative. Noting that the program began as a reaction to foreign pressure, he went on to argue that

it had no clear educational rationale, that as a whole it was not going very

well, and that numerous problems remained. Since most of the foreign

youth were not licensed teachers, he concluded, the acronym ALT was itself a misnomer and should be replaced by ETA (English teaching assistant). This skepticism among JTLs was confirmed over the next few weeks

at other conferences I attended. I even overheard one JTL refer to the "ALT

problem" while talking with a local board of education official.

In my own observations of team-taught classes, I was repeatedly

struck by how the Japanese teachers' strategies clustered around the two

extremes. Either the entire class is turned over to the foreign teacher, or

the foreign teacher becomes part of the furniture of the regular classes as

a kind of human tape recorder. Often a single class was divided into

conversation-oriented activities (which the ALT leads) and exam-related

study (in which the ALT assumes a peripheral role). In both cases, the

possibility of spontaneous interaction in the classroom is minimized. My

observations were confirmed by a national survey conducted by the Institute for Research in Language Teaching in 1988. When asked how

labor is divided in team-taught classrooms, 30 percent of senior high

teachers reported that they let the foreign teacher take charge of the

class, 25 percent responded that they themselves remained at the center

of class instruction, and 36 percent said that they shared teaching responsibilities. As to whether Japanese teachers of English were satisfied

with team teaching, half of the junior high school teachers and close to

two-thirds of the senior high school teachers said they had reservations

about the approach.20