Imponderables: Fun and Games (14 page)

Read Imponderables: Fun and Games Online

Authors: David Feldman

I

f dugouts were built any higher, notes baseball stadium manufacturer Dale K. Elrod, the sight lines in back of the dugout would be blocked. Baseball parks would either have to eliminate choice seats behind the dugout or sell tickets with an obstructed view at a reduced price.

If dugouts were built lower, either the players would not be able to see the game without periscopes or they wouldn’t have room to stretch out between innings.

Submitted by Alan Scothon of Dayton, Ohio.

H

as there ever been a child with a bicycle who has not pondered this Imponderable? We got the scoop from Dennis Patterson, director of import purchasing of the Murray Ohio Manufacturing Co.:

The rear sprocket cluster utilizes a ratchet mechanism that engages during forward pedaling, but allows the rear wheel to rotate independently of the sprocket mechanism. When one ceases to pedal, the wheel overrides the ratchet and the clicking noise is the ratchets falling off the engagement ramp of the hub.

The ramp is designed to lock engagement if pedaled forward. The ratchet mechanism rides up the reverse slope and falls off the top of the ramp when you are coasting or back pedaling.

Submitted by Harvey Kleinman and Merrill Perlman

of New York, New York.

A

s if the pathetic trajectory of your ball weren’t punishment enough, a mis-hit in golf is likely to be accompanied by a sustained stinging sensation in the hands. If a shot hurts, you either haven’t struck the center of the ball or, even more likely, you haven’t hit the ball with the sweet spot of the club. Dr. John R. McCarroll, of the Methodist Sports Medicine Center, explains:

Hitting the toe or the heel of the club causes more stress to be sent up the shaft and radiated into the hand. It is essentially like holding on to a vibrating hammer or like being hit with a hammer on the hands because the stress comes up and causes the hands to absorb the shock.

John Story, of the Professional Golfers’ Association of America, explains that not all golf clubs are alike when it comes to inflicting pain on the duffer. A mis-hit on a driver (or any other wood) is much more forgiving than the iron, which has a harder head and therefore creates much more vibration. The vibration from the mis-hit of a driver gets lost in the long shaft.

Dr. McCarroll adds that advances in club manufacturing have lessened the problem of hand stings: “The newer shafts such as graphite and casted clubs cause less pain to your hands than the classic forged club with a metal shaft.”

Submitted by Ron Musgrove of San Leandro, California.

T

heir sole purpose, according to Al Vanderneck, of the American Bowling Congress, is to look pretty. Part of Vanderneck’s job is to check the specifications of bowling equipment, and he reports that without the stripes, the pins “just look funny.” The area where the stripes are placed is known as the “neck,” and evidently a naked neck on a bowling pin stands out as much as a tieless neck on a tuxedo wearer.

Actually, we almost blew the answer to this Imponderable. We’ve thrown a few turkeys in our time, and we always identified the red stripes with AMF pins; the other major manufacturer of bowling pins, Brunswick, used a red crown as an identification mark on its pins. So we assumed that the red stripes were a trademark of AMF’s.

AMF’s product manager Ron Pominville quickly disabused us of our theory. Brunswick’s pins have always had stripes, too, and Brunswick has eliminated the red crown in their current line of pins. A third and growing presence in pindom, Vulcan, also includes stripes on their products.

We haven’t been able to confirm two items: Who started the practice of striping the necks of bowling pins? And exactly what is so aesthetically pleasing about these two thin strips of crimson applied to battered, ivory-colored pins?

Submitted by Michael Alden of Rochester Hills, Michigan.

Thanks also to Ken Shafer of Traverse City, Michigan.

Postscript:

Guess what? As of Fall 2005, the Brunswick crown is back!

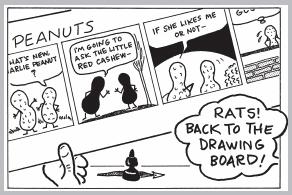

B

efore there was

Peanuts there was Li’l Folks

, Charles Schulz’s cartoon produced for his hometown newspaper, the

St. Paul Pioneer Press

, starting in 1947. Fortunes are not made from selling cartoons to one newspaper, however. So Schulz pitched

Li’l Folks to the United Features Syndicate, who was

interested in the work, but not the name of Schulz’s strip.

UFS perceived two possible problems. Schulz’s existing title evoked the name of a defunct strip called

Little Folks created by cartoonist Tack Knight.

And there was a comic strip that was already a rousing success that United Features already distributed—

Li’l Abner

.

Who decided on the name

Peanuts

? The credit usually goes to Bill Anderson, a production manager at United Features Syndicate, who submitted

Peanuts along with a list of nine other alternatives to

the UFS brass. The appeal of

Peanuts was obvious,

since as Nat Gertler, author and webmaster of a startlingly detailed guide to

Peanuts book collecting

(http://AAUGH.com/guide/) notes:

The name

Peanuts

invoked the “peanut gallery”—the inhouse audience for the then-popular

Howdy Doody

television show.

Charles Schulz not only didn’t like the name change, but also objected to it throughout his career. Melissa McGann, archivist at the Charles Schulz Museum and Research Center in Santa Rosa, California, wrote to

Imponderables

:

Schulz always disliked the name, and for the first several years of the strip’s run he continually asked UFS to change the name—one of his suggestions was even “Good Ol’ Charlie Brown.” Up until his death, Schulz maintained that he didn’t like the name

Peanuts

and wished it was something else.

In his essay on the

Peanuts creator, cartoonist R. C.

Harvey quotes Schulz to show how much the usually soft-spoken man resented the

Peanuts title:

“I don’t even like the word,” he said. “It’s not a nice word. It’s totally ridiculous, has no meaning, is simply confusing, and has no dignity. And I think my humor has dignity. It would have class. They [UFS] didn’t know when I walked in here that here was a fanatic. Here was a kid totally dedicated to what he was going to do. And then to label something that was going to be a life’s work with a name like

Peanuts

was really insulting.”

Gertler points out that when Schulz first objected to the name change, UFS held the trump cards: “By the time the strip was popular enough for Schulz to have the leverage, the name was too well established.” But in the media in which he had control over the name, Schulz avoided using

Peanuts alone,

as Gertler explains:

At some point during the 1960s, the opening panel of the Sunday strips (when run in their full format) started saying

Peanuts

,

featuring Good Ol’ Charlie Brown

rather than just

Peanuts

as they had earlier. Meanwhile the TV specials rarely had

Peanuts

in their title; instead, it was “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” “It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown,” and similar names.

In fact, we’re not aware of a single animated special that even contains the name

Peanuts

—the majority of titles feature Charlie Brown, and a significant minority Charlie’s untrusty companion, Snoopy.

So we are left with the irony that the iron man of comic strips, the giant who created the most popular strip in the history of comics, who made more money from cartooning than anyone, detested the title of his own creation. Schulz probably appreciated not only the royalties from foreign countries, but the knowledge that especially in places where peanuts are not an important part of the diet or had no association with children, his strip was called something else:

Rabanitos (“little radishes”) in South

America,

Klein Grut (“small fry”) in the Netherlands,

and the unforgettable

Snobben (“snooty”), Sweden’s

rechristening of Snoopy.

Submitted by Mark Meluch of Maple Heights, Ohio.

F

or those of you who didn’t have anything better to do than obsess about Nintendo in the early 1980s, Donkey Kong is a game created by Shigeru Miyamoto, the most famous video game creator on the planet. Donkey Kong featured a diminutive hero, Jumpman (whose name was later changed to Mario), who had a much larger pet, a gorilla. The gorilla did not exactly bond with his “master,” and conveyed his wrath by kidnapping Jumpman’s girlfriend, Pauline, climbing a building, and hurling barrels and other missiles as our hero attempted to rescue his sweetheart. If the little man managed to reclaim her temporarily, the gorilla snatched Pauline away again. As the game progressed, each level made it harder for Jumpman to succeed. But regardless of what level the player progressed to, nary a donkey was seen.

So why the donkey in the title? Although some fans insist that the “donkey” was a misheard or mistranslated attempt at “Monkey Kong,” Miyamoto has always insisted otherwise. On his tribute site to Miyamoto (http://www.miyamotoshrine.com), Carl Johnson includes an interview with Miyamoto at the Electronic Entertainment Exposition, where the game’s creator addresses this Imponderable:

Back when we made Donkey Kong, Mario was just called Jumpman and he was a carpenter. That’s because the game was set on a construction site, so that made sense. When we went on to make the game Mario Brothers, we wanted to use pipes, maybe a sewer in the game, so he became a plumber.

For Donkey Kong, I wanted something to do with “Kong,” which kind of gives the idea of apes in Japanese, and I came up with Donkey Kong because I heard that “donkey” meant “stupid,” so I went with Donkey Kong. Unfortunately, when I said that name to Nintendo of America, nobody liked it and said that it didn’t mean “Stupid Ape,” and they all laughed at me. But we went ahead with that name anyway.

In some other interviews, Miyamoto indicates that “donkey” was chosen for its usual connotation in English—stubbornness. In his book on Nintendo,

Game Over: Press Start to Continue

, David Sheff writes:

When the game was complete, Miyamoto had to name it. He consulted the company’s export manager, and together they mulled over some possibilities. They decided that

Kong

would be understood to suggest a gorilla. And since this fierce but cute

Kong

was donkey-stubborn and wily (

donkey

, according to their Japanese-English dictionary, was the translation of the Japanese word for “stupid” or “goofy”), they combined the words and named the game Donkey Kong.

At least one party wasn’t happy with Nintendo’s name—Universal Studios, which owned the copyright for

King Kong

. Universal sued for copyright infringement, claiming that the video game mimicked the basic plot of the movie (man climbs building to save his girlfriend from the clutches of a giant ape). Universal lost on the most obvious of grounds—the judge ruled that the movie studio did not own the rights to

King Kong

. Nintendo won the suit without, unfortunately, having to justify the nonexistence of a donkey in Donkey Kong.

Submitted by Darrell Hewitt of Salt Lake City, Utah.