Imperial (78 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

José had already gone back up into the light. I remember gazing up through the rectangular floor-hole at the boy in the church; he might have been the pastor’s son; nobody ever introduced him; he was crouching down up there in the sky with his hand on his knee, gripping the plank which ran across the hole; he was foreshortened and far away, framed by pale ceiling-blocks which were mildewed and also charred by this or that great fire.

Meanwhile, on that earlier June day in that tunnel under the Victoria, I had seen that brick wall and turned back to the middle chamber where beside another tall narrow doorway which led into more blind-walled darkness, we saw a desk, and approached it without any great expectations since it was not so many steps away from the entrance to this place; all we had to do was turn around and we could see the supernaturally bright daylight of Mexicali burning down into the stairwell. I remember that a spiderweb as wide as a hammock hung on the wall; I remember how dismally humid it was in that place; I could almost believe Mr. Auyón, who’d claimed that of course the Chinese never lived underground because that would have been too uncomfortable. In other words, I couldn’t help but assume this desk to be a counterpart of the first tunnel’s safe, more specifically speaking the first tunnel’s Sentry model 1230, which sat upon the skeleton of a table which might once have had a glass top, lording it over broken beams and pipe-lengths. Dust and filth speckled the top of the safe; behind rose a partly charred concrete wall. The door gaped open. Inside was nothing but dirt.

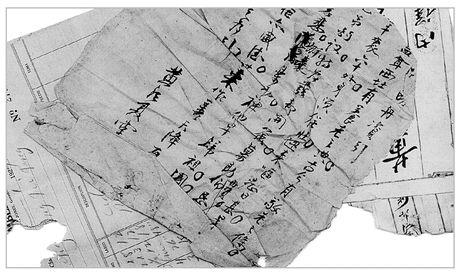

But as it turned out, under the Restaurante Victoria, in that rolltop desk whose writing surface was wood slats now beginning to warp away from one another just enough to let the darkness in between them, lay treasures far more valuable to me than any Chinese gold: a hoard of letters, some of them rat-gnawed, all of them smelly, moldy and spiderwebbed; when Yolanda Ogás saw them she caught her breath, standing rigid with excitement against the wall whose pale sea-waves of stains were as fanciful as the serpent-plumes of painted Chinese dragons; they warped and curved, white-edged and sometimes dark-patched upon that wall where Yolanda stood rigid and rapt, watching Miguel bend over the desk, fingering the old letters which had been crammed into blackened drawers for who knows how long. The darkness was hot, wet and slightly rotten. For a long time the Chinese bent over a book of blank forms;

132

then he rose and turned away indifferently.

Yolanda was the one to ask whether any of the tunnel letters could be borrowed. Miguel, who was a nice man, assented at once. One of my Chinese translators would later remark that he

didn’t seem to care in the least about

the tunnels

or what [they] might have been used for in the past.

When I chatted with him upstairs, in the richly glowing shade of the Restaurante Victoria itself, looking out through the lingerie-translucent curtains and the double glass doors with the red ideograms on them, the white rectangles of the streetwalls, and dried-blood-colored gratings of other Chinese businesses, the world one-third occluded by angle-parked cars and trucks, I found that he didn’t want to talk, because he’d only been here for twenty years, which, so he reminded me,

wasn’t long enough to voice an opinion.

He referred us to the Chinese Association. There were actually either twenty-six or twenty-eight of those, but he meant the Chinese Association whose head was a certain Mr. Auyón.

I photocopied Yolanda’s originals and took the copies back Northside to translate them. Later I sent my interpreters back to gather in the rest of the letters. You will find a few of them quoted here. For me they bring alive the time when there was light in the partly stripped chandelier, when that ceiling whose fanciness has long since been gutted into occasional waffle-pits of darkness was still whole, when the stacked tables were still laid out for reading, drinking, arguing and gambling, a time before the walls were stained and the ceiling-squares dangled down like laundry on the line. I am not saying that it was necessarily a better time for the Chinese; I wouldn’t presume to know that, and many of the tunnel letters are very sad, for instance this one, an undated message from a wife in China to her husband here in Mexico; perhaps he brought it downstairs to ask his Tong brothers what he could possibly do:

Everything goes well at home, except that my father-in-law cannot understand why there is no letter from you. Father-in-law questioned money sent via Hong Kong via Rong-Shi, and Rong-Shi denied receiving money. We borrowed money from neighbors. Father

in-law is not in good health. Please send money home. Also, when you send money home, do not send money via Rong-Shi, but addressed to . . .

Thinking of you. The way I miss you is heavy and long; however, the paper is too short to carry the feelings.

When my Chinese proxies Clare and Rosalyn Ng, about whom more shortly, saw this tunnel a month later, this is how Rosalyn saw it:

The red sign above the stairs with the Chinese writing says luck/celebration/happiness. It is a very common character/ word/phrase still used today, especially at weddings,

and the Chinese waitress from the Dong Cheng Restaurant down the street said the same when I brought her here.

But I highly doubt it was written/hung there for that specific purpose, even though the place would have been ideal for a wedding with its exquisite interior decorations and loads of round tables and chairs . . . You thought the place might’ve been used for gambling. My mom and I . . . find that greatly possible . . . It might also have been a place where people gathered, just like a community club or tong, and business matters were taken care of in back rooms. Also, the numerous tables and chairs would be available for anyone who wished to sit down, read the newspaper, or just have a conversation with a friend or neighbor. The tables also would have been great for playing mah-jongg, gambling or not. Either way, I believe the place was for public use and for entertainment purposes, especially since the sign at the entrance embodies that sentiment of fun and celebration . . .

Then suddenly I could almost see it; I imagined that I almost knew it; I know so well that much of the life in this hot harsh bright place which I call Imperial is lived indoors, in the lush nourishment of secrecy; cross the line to Northside, head for the Salton Sea, and when you get to Niland you’ll find the I. V. Restaurant (Chinese Food to Go;

BURGERS;

Sandwiches

)crouched beside the empty road. From the outside you might think that it was closed; the curtains are drawn; but when you come in, it’s cool and dark and loud with the lively roaring of the air conditioner; the Chinese waitress scoops relish out of a huge plastic bucket; old men with bent backs sit in plastic chairs, eating at the counter; a Hispanic couple gaze at each other from across a small table; his massive arms are folded; she reaches for the salt, then wipes herself with a napkin. It’s a hundred and fifteen degrees outside, so people stay and stay and stay. Another root beer float, please, with lots of ice cream! Another medium-sized soda as big as a house! Drink it down to appease the need. Now order another one and make it last! How cool and wonderful it is in here; if only we could hide from the sun all day . . .

Now imagine Mexicali back in, say, 1920, with no air-conditioning, the unpaved

avenida

blank and empty except for a single old woman in a white shawl limping across the blinding dirt (now the

avenida

’s asphalted, to be sure, and even late at night in Mexicali one feels the heat coming up from the pavement); imagine being Chinese and knowing that the nearest Chinese consulate was all the way in Ensenada; imagine longing for shelter not only from the hellish brightness of each day, but also from the people and institutions of Mexico herself whom one did not understand and by whom one was not understood.

133

They live together like cigarettes. They came out like ants. Goddamned gooks!

Ever since 1915, Chinese had been fleeing their murderers in Sinaloa and Sonora. Other Chinese kept coming all the way from Canton and Hong Kong to work for the Colorado River Land Company. The braceros of 1902 who’d saved up enough money to do so were sending for their relatives. Mr. Auyón insists that by 1919

the Chinese called the city of Mexicali “Little Can-Choo” (the capital of Canton), because there were more Chinese than Mexicans.

If this were in fact the case, one can imagine what the Mexicans were saying about the Chinese. In 1921, Mexico passed its own version of Northside’s various Exclusion Acts, and banned further importation of coolie labor.

I was beginning to see that the tale of the tunnels was not only the tale of myths and dreams, but it was also the story of how and why one world, which was dominant, hot and bright, forced the creation of another, which was subterranean and secret. Just why did they live together like cigarettes? Was it simply because they liked to?

Here is how that photo-studio owner, Mr. Steve Leung, who as I’ve said was a third-generation Chinese immigrant and whose birth certificate read Esteban León, described the differences between Chinese, Mexicans and Americans, and you should remember that his words were spoken in 2003, exactly a hundred years after Mexicali was founded; and please understand that Mr. Leung was sufficiently Mexicanized to keep an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on the wall of his small triangular darkroom. In 1920, differences and perceptions of differences would have been even greater.—Mr. Leung said:

The Mexicans like to drink alcohol and as well to fool around with women, same as the Chinese would like to gamble a lot and they’re workaholic. As for Americans, they like to enjoy their life, but they want to work, but they’re not willing to sacrifice too much of their own time. Culturally thinking, Mexicans don’t have the precise discipline that the Americans have, and yet the Chinese people is still not yet a developed country, because they overlook their own needs; they’re always thinking of the next generation. Whatever your generation was passed to you materially, you can add one dollar or one percent, and pass it on to the next generation, and you succeed in the goal that was expected of you. Now, the American says, you got to build your own wealth; you don’t receive anything from the parents’ generation. And the Mexicans, they normally pass on debts, more than adding on anything. Businesswise, I think I can describe the culture like this: Always an American is thinking this year,

What is the projection of profits?

When he asks this of my Chinese friend, this Chinese owner, he says,

Forget about profit;

he says,

we’re going for sales right now, penetration in the market; we’re going for a hundred years.

134

The Mexican right away will put as many relatives and friends into the payroll, see how much he can spend without putting any in.

The Mexicans said:

They live together like cigarettes.

The Chinese replied:

They normally pass on debts, more than adding on anything.

Rosalyn Ng reported to me that

for a long time,

Mr. Auyón

went on and on about how Chinese need to come together and stand strong as one all over the world, especially when they immigrate to other nations. Thankfully, the Chinese already had this concept of unity . . . From this tight knit sense of closeness, tongs

135

began to develop based on the common bond of having the last name,

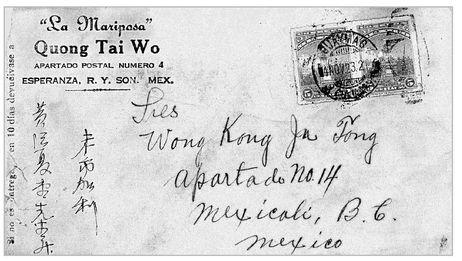

a case in point being the Wong Kong Ja Tong, whose letters rotted beneath the Victoria.

136

Or, as a Mexican might put it,

they live together like cigarettes.

Members of a Tong who had never met personally seemed to have been capable of instant mutual trust, as this letter from 1924 implies: