Imperial (49 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

“THE WONDERFULLY FERTILE VALLEY OF THE NEW RIVER IS NOW BEING OPENED UP”

Hence, I imagine that his dreams fly toward San Diego County, which according to its own directory for that year is

larger than the State of Masachusetts . . . For one hundred and fifty miles it borders on the Mexican boundary; the Colorado River separating the eastern part of the county from the territory of Arizona . . . The wonderfully fertile valley of the New River in the eastern part of the county is now being opened up . . . The richest and most fertile section of the state . . . will soon teem with life, furnishing homes for thousands of families.

In spite of this praise, in spite of the twenty-one residents accounted for in Ogilby or Ogilvy, the directory has no listing whatsoever for the town of Imperial—another indication that Wilber Clark must be a gambler.

THE ARRIVAL

So what do the Clarks see upon their emergence from L.A.? Maybe something like what Raymond Chandler will decades later:

This is the ultimate end of the fog belt, and the beginning of that semi-desert region where the sun is as light and dry as sherry in the morning, as hot as a blast furnace at noon, and drops like an angry brick at nightfall.

That sums up Pomona, which was laid out by a company managed by Mr. Holt’s late father. After Pomona the semi-desert region becomes the desert region in which Riverside remains a modest oasis; then it’s definitely blast furnace, all right.

How long would it have taken him to get to Imperial? I asked Carl Calvert.

I’d say two days. It was difficult, because it was sandy. Dry sand. People would carry with ’em burlap bags and like that, to avoid getting stuck.

(In 1909 an auto touring club will motor from Oakland to Maine. They’ll report that the very worst stretch of road is from Palm Springs to Indio.)

I see a view of the road through Brawley in 1908, running wide, sandy and rutted; the caption says that

clouds of dust and sand pursued each automobile,

except when rain turned it to muck. I imagine our voyagers choking on dust, Miss Clark with a scarf over her mouth.

A 1921 Studebaker, manned by four stalwart and begoggled adventurers, skids through the sandy ruts on the road near Blythe, typical of early desert roads.

I suppose that our explorers stop again amidst the tent-houses of Indio, some of which are now a good decade and a half old. But the town is scarcely a green spot. Northwest of the Salton Sink, the Coachella Valley remains almost dry, the only exception being the Apostle Palm Oasis, which will later burn, then be superseded by the junction of Indio’s Madison Street and Avenue 38. In 1903, darkhaired Howard Gard stands with his hands in his pockets; the photo does not allow me to distinguish whether he is wearing vest or coveralls; slender palm-trunks rise behind him, and then there is his dark-windowed grocery store, which is also the post office; perhaps he waited on the Clarks in 1901: Steam comes out of the car. Chickens run away. The travellers alight. They buy water, and perhaps fresh fruit. Horse manure desiccates in the streets.

They continue south to Coachella, some of whose native trees persist. (I see a faded photograph of men doing something around an open boxcar. The caption reads:

Fred, Paul and I loading 65,860 pounds of mesquite which we hauled from my farm and sold for firewood to an LA firm.

) The town is getting platted out; a convocation of seventeen men has lately abolished the old appellation of Woodspur. I presume that Wilber Clark sees the wooden water tank over Jack Holliday’s well; surely he must drive past the miraculous white spurts of artesian wells. Could there be any of those where he’s going? No doubt; for George Chaffey has promised us:

WATER IS HERE

. Imagine a ranch—for instance, the Wilfrieda Ranch—built around such a pillar of delight! Imagine a home of comfort and cool green abundance.

He drives on. Arabia is not yet a ghost town. Mecca is still hard-pressed from the total loss of last year’s melon crop, thanks to a hundred-and-thirty-five-degree spell in June.

Ahead of them glares the Salton Sink. The two rival salt companies have just reconciled and are mining

this wonderful saline deposit

in mercantile concord at the Southern Pacific spur line called Salton.

It is common to find the mercury here as high as 105 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade . . . and in the full sun’s rays 130,

so, needless to say, the companies employ Indians to plough the salt. I would not suppose that Wilber Clark’s party stops here, but they likely motor past it, for the wagon road to Old Beach, nowadays known as Niland, to which Leonard Knight bicycles from Salvation Mountain to get his water; his is the railroad disembarkation for many Imperial immigrants.

In a short time that point will be the base of supplies for the Imperial country.

So the Clarks might pause in Old Beach, for the same purpose as Leonard.

In 1901, most of Imperial townsite’s immigrants arrive in October. Wilber Clark is a trifle more cautious—or perhaps he simply takes longer to make up his mind. An item in the

Los Angeles Times,

dated 28 November 1901,

77

informs us that

the Imperial country continues to fill up, more than fifty people having come in the last week.

Among the recent arrivals in the valley are Wilbur

[

sic

]

Clark and sister, and their father, from Los Angeles. Clark is building a residence in Imperial, and will at once put in a hardware store.

In November, Imperial is almost cool. They stop. They gaze at the saltbushblotched desert around Imperial City. In a month, Margaret Clark will already be postmistress.

THE ASTRONAUTS

As Judge Farr implied, the love and labor of Wilber Clark’s life will be the Wilfrieda Ranch, also known as the Wilfreds Ranch. At this point in time it remains “unimproved,” which is to say waterless. What might be its appearance in that condition? Here’s the residence of Joseph Becker on Eighth Street, one mile west of Imperial Avenue: A squat cone roofs it, almost like a miniature Signal Mountain; it has a shaded porch all the way round, with three steps between it and the flat dirt which goes on forever; near the leftward edge of this old photo a gentleman stands on the topmost step, while a lady, beautifully proportioned but unknown, since her hatted face entirely has been shadowed by the awning, sits in a coach behind two splendid white horses. Oh, but Imperial is flat and grey all around them! Their house crouches like a newly landed flying saucer; how can this extraterrestrial couple (could they likewise hail from the planet of Los Angeles?) hope even to breathe the air of Imperial, which feels nearly as hot as the air of Venus (seven hundred degrees Fahrenheit)? Imperial’s a science-fiction story. For that matter, how can they find anything to drink?

But then what happens? George Chaffey opens the gates of the Imperial Canal, and the Colorado rushes down the riverbed of the Alamo!

WATER IS HERE

.

Can you imagine it? It must have been as fantastic as the scene in H. G. Wells’s

The First Men in the Moon

(published that same year): Sunrise’s unbearable light strikes a crater drifted high with frozen oxygen, and promptly slushifies and liquefies the snow into air,

78

then seedcases burst and grow into spiky olive-green plants, at which point the insectoid Selenites open the shafts beneath, and out come the pale white mooncalves to graze.

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS.

But for now the moon continues to partake of a decidedly lunar character; and Wilber Clark has not yet even purchased the site of the Wilfrieda Ranch. His home in Imperial City is provisional, like irrigation itself.

So for the time being he plies the retail trade in town; that’s his contribution to Empire. More specifically, as we’ve just been informed, he opens Imperial’s first hardware store (which Judge Farr, always good for such details, informs us will soon be bought by A. L. Hill), while his busy sister starts a stationery business which in due course she sells to H. E. Allat. One day in the Pioneers Museum, turning over photograph after photograph, I came across an oval portrait of

Miss Clark—Imperial Valley’s first postmistress. Later became the wife of Mr. Archie Priest,

who presumably precedes or succeeds W. H. Dickinson of Yuma. Since pioneers had to do many, many things,

she was also a school teacher.

Curlyhaired, fairskinned and ovalfaced, she wears a lace scarf tied tight around her collar and a light-colored quilted dress of many vertical stripes. She gazes far away. Her jaw is slightly clenched, perhaps due to the stress of being photographed; but her face is so very smooth and young that the impression escapes unpleasantness. She’s a beautiful, serious lady of thirty-six years—ripe for marrying.

What might her brother’s hardware store have looked like? Here’s another photograph from the Pioneers Museum: A man in a Western hat leans his wrist on a post; he has a moustache and the half-sad, half-insouciant expression of a French-Canadian

voyageur;

beside him stands a prim-looking, plain woman in a pale ankle-length dress; she wears no hat; from them radiates Imperial emptiness with a stake in it; behind them is a building, slightly grander than a shed, of vertical planks, with surprisingly large square compound window-panes in its facade; the caption reads:

First Post Office and Hardware Store, Mr. and Mrs. J. Stanley Brown.

First hardware store where? Consulting both Judge Farr and Otis P. Tout, I discover no answer.

W. W. Master is working sixty horses on our lateral canal, which will be fourteen feet wide! A drugstore is to be

put in immediately,

not to mention a harness store. Los Angeles must be proud. Mostly, I suppose, Imperial is Tent City, as Indio was and Salton City will be in 1958. I quote from an envisoner of that third epoch:

There were enough tents to house a circus now, flying pennants from their masts as if for a coronation or a festival.

Or, if you would rather repeat the sermon of William Smythe:

The essence of the industrial life which springs from irrigation is its democracy.

In the spring of 1902 we hear that the first four brick buildings of Imperial will be erected soon; one is Wilber Clark’s hardware store. Oh, Imperial’s dreams are all coming true! As two of her citizens will later recall,

water was in the ditches, seeds were in the ground, green was becoming abundant, and the whole area was dotted with the homes of hopeful, industrious, devoted persons.

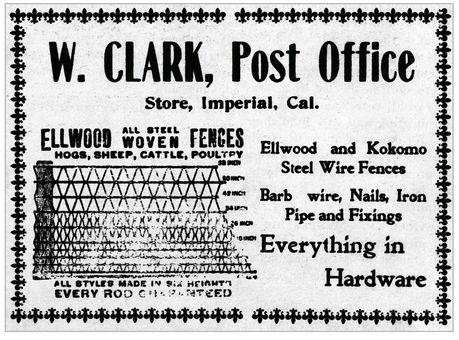

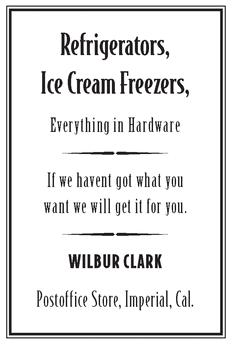

He runs an advertisement, not the largest, not the smallest:

On 20 September 1902, Wilber Clark registers a purchase of land from the Imperial Town Company. Is this a belated formality connected with his hardware store, or has he become a petty W. F. Holt, a speculator like so many others?

The following month, the Farmers’ Institute calls the roll in

the new brick block of the Imperial Land Company.

Signing the roster, widely separated by other names, are W. F. Holt and Leroy Holt, Margaret S. Clark—so she remains yet unmarried—and old John Clark. Wilber Clark’s name is absent. The newspaper reports that he has gone with some friends to Carriso Creek for a week’s hunting.

We have the temerity to suggest that they were possibly hunting oil land but were informed that such was not the case.

Nor does he appear in the self-congratulatory

Valley Imperial

published by the county historical society half a century later. We’re informed that the Edgar Brothers, as had the Clarks, rolled into the town of Imperial in 1901;

they soon founded a farm implement and heavy hardware business in Imperial . . . Early in the firm’s history a policy of offering only first class merchandise with guarantees . . . was decided and adopted.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life. By 1903, the Edgar Brothers own a store in Calexico; soon they have branches in Brawley and Holtville, too. What about Wilber Clark? He’s straining his reddish-brown drinking water out of the ditches with the rest of them.