Imperial (156 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

In 2005, Mexico files suit against the United States in an attempt to halt the lining of the All-American Canal, which will result in a loss to the Mexicali Valley of between sixty-six and eighty-one thousand acre-feet per year. The practical effects of Northside’s frugality will be a fourteen-percent decrease in the water that the valley can draw on, a nine- to twenty-foot drop in the water table near the canal, and significantly increased salinity. One commentator worries about a possible eco-catastrophe. Another predicts a nine-percent decrease in crop productivity. In other words,

there is an abundant supply of water.

In 2003 Richard Brogan had said to me: Have you ever been down along the Mexican side of the All-American Canal? And now the Americans are talking about lining the canal. Imagine what’s going to happen there. That’s how they live there, from that water.

Stella Mendoza, the former President of the Imperial Irrigation District, had said: Well, you know that now that they’re going to line the All-American Canal, and that water that’s been seeping out—it’s about sixty, seventy thousand gallons—the Mexicali farmers have been pumping that out. What’s going to happen to them? That’s something that we as the IID need to talk about. The lining, the engineering has already started, so it’s going to happen within the next five years.

The San Diego Water Authority refused comment as usual.

(The private investigator in San Diego comforted me by explaining that Mexicans were worse than Americans: They’ll starve out a whole

colonia

of people to sell water to the United States. If you want to exploit a Mexican, put another Mexican in charge! The exploitation will reach heights we can never dream of.)

There was a hairdresser in Luis Río de Colorado named Evalía Pérez de Navarro. She had lived in that place since about 1968. In 2003 she said: My grandfather had a ranch thirty years ago. There was like a canal, a very big canal. When I was seven or eight and on Grandfather’s ranch, it was very pretty. There used to be a lot of foliage—small bushes and small pines—and it kept the water from spreading out. My uncle was the President of the organization for cleaning the water.

When did the river start to change?

Thirty or forty years ago. The first thing I noticed was that I could see a lot of salt on the highway and the cotton wasn’t growing as much.

No one drinks out of the tap anymore, she said. If you spill on the floor, it leaves white salt. If you drive to Mexicali, you can see where the salt has deposited on the land. It happens when it rains. A week or two after the rain has dried, you can see the white part. And in my garden, some things are more difficult. For gardening we buy soil from other places. We can use it a year or less.

So, how would you describe the water situation?

It’s not normal, but it’s not something that we can really fix.

And in Mexicali?

The water in Mexicali is bad. It smells bad.

296

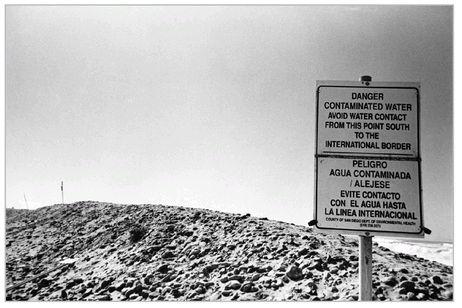

Pacific Ocean, Imperial Beach, 2002

IT’S ALL RELATIVE

Please recall that at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the Imperial and Mexicali valleys first began to drink from the Colorado in earnest, the salinity of that river-water was four hundred parts per million. Now at the century’s end five Mexican scientists lament the impending loss of All-American Canal seepage, treasuring this

good-quality groundwater

whose salinity is nine to thirteen hundred parts per million. Northside’s act will nearly double the salinity of Mexicali’s aquifer over the next twenty years. Cotton, wheat, rye and sorghum production should be unaffected; alfalfa will decline by twenty percent and green onions, a crop which

generates the largest need for labor in the area,

by fifty-eight percent.

But why despair? Mexican Imperial might be able to save some water by irrigating as efficiently as they do in Northside . . .

NEWS FLASH FROM CALEXICO

By the way, how

is

water quality up in Northside?

The water comes in out of the cement ditch there and it comes into our own cistern, Kate Brockman Bishop was saying to me. That blue pump tower down there, that’s water we give to the Mexicans that goes to Ensenada. It’s been there fifteen, twenty years.

I asked about salinity on her land, and she said: It’s worse now than it used to be.

NO TIME TO WORRY

In 1985, a paper was delivered by Eduardo Paredes Arellano, Secretaria de Agricultura y Recursos Hidráulicos, Mexicali.

The greatest danger threatening the future of our civilization is the rapid reduction of water resources, . . .

he advised us. Someday industries might fail and cities disperse due to lack of water!

“We just ask that water is used efficiently so that we have an ample water supply for new developments and existing homes,” says Anderson.

Fortunately, Mexican Imperial was enjoying a period of high rain in those years: Between 1979 and 1981, nearly nine thousand million cubic meters of Río Colorado water drained into the Mexicali Valley.

WATER IS HERE

. Moreover, the aqueduct from the Río Colorado to Tijuana was nearly done; ten more waterworks were proposed. Then Baja California would enjoy an abundant supply of water, I’m sure. Here came still another suggestion, made in a spirit of sincere international neighborliness:

It should be pointed out that along the international boundaries between Mexico and the United States the water basin of the Tijuana-Alamar rivers is one of the few that flows toward the United States of America, for which reason its immediate exploitation,

in other words its complete retention by Mexico,

is required and recommended.

More wonderful news: In Irrigation District 014 of the Colorado River, which included Mexicali, the authorities of Mexico were working with the Banco de Crédito Rural to “recuperate” salt-infiltrated soils. We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

It is pertinent to point out that all of the privately owned wells for agricultural uses

297

have outlived their usefulness,

which must mean that they’ve gone salty or dry.

Therefore it is necessary to implement the financing that would allow their total rehabilitation.

In Mexican Imperial, people must buy two kinds of water: the kind they drink, and the other kind. At the turn of the century, household water (for washing and the like) cost between a hundred and two hundred pesos a month. Bottled water was the same again or more.

298

Northwest of San Luis Río Colorado, in the

ejido

called Ciudad Morelos, Don Carlos Cayetano Sanders Collins told me: It’s not hard to get it, but the problem is, it’s very expensive. Although I only pay a hundred and fifty pesos a month for what we use in our household, I pay ten pesos per liter for agricultural use. One five-day cycle takes a hundred and ten liters for my thirty hectares. So it costs me four or five thousand pesos per month.

That

is

expensive, I agreed.

It comes from electric sprinklers, he added, a little proudly, I thought.

Is there much salt in the water, or not much?

He nodded. It puts my crops in danger. But ten or fifteen miles up the road, there’s Presa Morelos. When it goes through the

presa,

then it’s okay.

Which of your crops is the most endangered by salt?

Cotton.

299

And which crop needs the most water?

It’s all the same.

Are you worried about the future of your water?

There’s no time to worry. I have enough to do, paying for it now.

E. J. Swayne, townsite of Imperial, California, 1901:

It is simply needless to question the supply of water.

IN WHICH THE ARTESIAN WELLS COME BACK TO LIFE

Who are you and I, to disagree with E. J. Swayne? Leonard Coates from Fresno backs him up. And if you want more proof, do you remember all those artesian wells which a work of alarmist fiction entitled

Imperial

insists have dried up? In the Motor Transport Museum in Campo, where the former Julian stagecoach lay in state (a quack in Borrego Springs replaced its transmission with a generator in order to sell his patients therapeutic electric shocks), old Carl Calvert, having shown off this marvel to me, referred in a voice of experience to a carbonated well from the turn of the last century; one could still see it bubbling, he said; moreover, there’d been artesian wells in Rancho Santa Fe just last week!—Do you know what fed them? he laughed. Runoff from lawn irrigation from a development up the hill . . .

Chapter 157

AS PRECIOUS AS THIS (2003)

And behold the people, the subjects are perishing! . . .

The breast of our mother and father, Lord of the Earth, is dry . . .

—Aztec hymn to Tláloc the rain god

H

ow will Tamerlane’s warriors feint? In which poison will they dip their arrows ? American Imperial warns

My Fellow Farmers

that here’s what will happen:

MWD will pay higher prices for short-term water transfers to maintain the appearance of reliability, while at the same time attacking agricultural uses, on the basis of inefficiency or whatever, in order to procure a long-term water supply . . .

... for instance, the All-American Canal, which flows blue or brown or grey, depending on the sky, between berms of dirt, with reeds on either side to give the pretense that there is more to it than utility; once the canal gets lined, the reeds will die. Here’s Pilot Knob, a rolling purplish dark hunk of something volcanic, sprawling on the horizon with white streaks of salt or mineral wriggling down it. Not far away runs a long white wriggling geoglyph of the four-headed snake which the Quechan creator-spirit Kumat threw into the sea a long time ago, to save people from its rattles. The snake came back, and Kumat had to kill it with a stone knife. Then another snake of reddish-brown water slithered here, when George Chaffey opened his main gate and the Imperial Valley began to turn green.

And the All-American Canal bores on through the desert as far as I can see in both directions, just dirt-lips and a smile of water in between; far away, perhaps in Andrade, a child’s voice takes to the wind.

MWD will pay higher prices.

MWD is but one of Tamerlane’s divisions. Don’t forget San Diego, Coachella, Nevada, Arizona, Interior . . .

It is simply needless to question the supply of water.

And so California’s entities argue angrily, pettily, and pathetically about who is using water best. Whose proof of reasonable and beneficial use will prevail?

Here is how Imperial argues.—Wait; I admit that there

is

no one Imperial. The water farmers draw the line against the farmers of cantaloupes, lettuce and tomatoes. (Richard Brogan shook his head and said: The sad part of it, a lot of these families are starting to feud. The old men put something together during the Second World War and accumulated thousands of acres. Now they got sons and daughters who are feuding).

300

—But if there

were

one Imperial, and if there were a “we,” this is how we would argue against the world:

Even American Imperial’s archfoe, the Bureau of Reclamation, confesses that our “on-farm efficiency” of water use in Imperial has achieved between seventy-two and eighty-three percent over the past sixteen years; while Coachella’s was only fifty-seven to seventy percent. As for Los Angeles,

MWD admits that 30-70% of residential use is in outdoor landscaping.

301

. . . MWD’s “efficiency” is thus well below 70%, and without careful measuring of the inflow or outflow.

While we in Imperial go innocently about our business of raising

food and fiber for the nation,

MWD spends too much time regulating flush toilets and not enough time slapping down golf courses. After all, Los Angeles is, among other things, the restaurant Crustacean in Beverly Hills, whose slogan is “Cuisine from Another World,” because

when you enter, you are drawn to another world: Indochina of the 1930s. An 80-foot-long river filled with exotic koi elegantly leads you to the dining room.

That’s what I call reasonable and beneficial use.

From 1936 to 2002 (the latest year for which I have figures), the Imperial Irrigation District has consistently used between two point seven and three million acre-feet per year—about twice what Mexico gets. No doubt it could save water, but certainly it has not drunk more than its allotment for a very long time.