Imperial (136 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

“THIS WAS

THE

GRAPEFRUIT COUNTRY”

But Imperial, as you may recall, is

NO WINTER -- NO SNOW

NO CROP FAILURES

Therefore,

we need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

In 1914, the Southern Pacific Railroad, possibly in alliance with the Chandler Syndicate, puts on the market

several thousand acres of mesa citrus lands

in the northern Imperial Valley

that are expected ultimately to be covered with rich lemon, orange, and grapefruit groves.

This project must have succeeded; because flavonoids, which may in turn be subdivided into flavanones, flavones and anthocyanins, beguiled the young schoolteacher Edith Karpen, when she arrived in Calipatria for the very first time in 1933. (I wish I could have seen what she looked like in that year. In her old age she was a very handsome woman.)

Her future husband showed her the sights.—He took me for a ride on the other side of town, she said, and all I remember about that was the overwhelming smell of grapefruit and orange blossoms.

Where was this? I asked in amazement, for the only thing I had ever smelled in Calipatria was feedlot stench.

We were going west, replied the old lady. Toward San Diego.

Why isn’t there citrus in that area now?

The water level later came up and killed them. When I came there, we still had some citrus on the ranch by Mount Signal.

Among the citrus, grapefruit was Emperor of Imperial! Grapefruit, you see,

on account of its earliness has a distinct advantage in California markets over fruit from other sections.

There might be another reason, if I understand the following numeric tale:

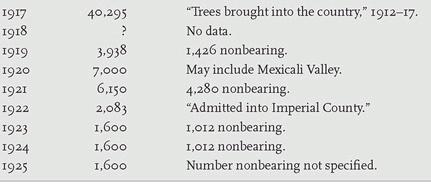

ORANGE TREES IN IMPERIAL COUNTY, 1917-25

I conclude from this data that unless the number of

trees brought into the country

was exaggerated by boosters, as perhaps it was, then within a decade, twenty-four out of every twenty-five of them had died.

And yet an eagle snarls, gripping a garland in its claws as it gazes away from an expanding metropolis at the sun-touched Pacific, which nicely curtails itself before the golden border of this award from the California Fruit Exposition of January 21-31, 1926. This certifies that Imperial County has been awarded

—First—

Premium for the Best Twelve Boxes Seedless Grapefruit Sweepstakes.

Indeed, how could Imperial not win the premium? For that very year, a particularly svelte Barbara Worth cocks her head at me from the ocotillo-studded reddish-mountained desert of an Imperial Valley Grapefruit label

(“No sugar required—The

Test is in the Taste”). In a label of unknown provenance from the Desert Grapefruit Company, Imperial, California, Barbara Worth, pensive and Stetsoned, helps sell Marsh seedless, because “The Test is still in the Taste.”

Unfortunately, IMPERIAL VALLEY GRAPEFRUIT WILL GET COMPETITON

,

warns the

Imperial Valley Press

in that same year. Imperial has planted fifty-five hundred grapefruit acres.

When bearing it will have to compete with about 125,000 acres of grapefruit now planted in other citrus districts of the United States.

I remember a front-page photo in the

Imperial Valley Press

of two men in suits touching a grapefruit between them, the better to commemorate this occasion

when Senator Shortridge of California converted Senator King of Utah from the latter’s belief that Florida had better grapefruits than California.

Oh, yes, Lord be praised; in the end Senator King sees the light and confesses:

The grapefruit of California, as well as all her other products, are known throughout the land. They are not only superior, they are supreme.

In 1929, Mrs. Adell Lingo buys a ranch called “The Pride of Niland” and plants more than four thousand grapefruit trees. Where are they now?

In 1930, Imperial pronounces itself the seventh most successful grapefruit producer of all counties. Ten years later I see Nana Lee Beck standing in her long white dress in the sandy sunny aisle between her family’s grapefruit trees in Calexico; but fifteen years after that, Brawley’s Mr. J. E. Harshman, Chairman of the Grapefruit Advisory Board,

which board is composed of the same people who put up the money for the advertising fund,

feels compelled to call for the same measures we have met with for lettuce, cantaloupes, green corn:

The orderly marketing of grapefruit, which will mean consumer satisfaction, is the only safeguard for the grapefruit industry in the desert area.

Why has acreage declined? Mr. Harshman agrees with Edith Karpen:

In the Imperial Valley grapefruit was planted on a great deal of acreage that was not suitable for the production of grapefruit due to the high salt and high water table ...The tops of the trees dried, the leaves turned yellow, the quantity of production fell very rapidly, and in those groves it was not economically feasible to continue with grapefruit so they were taken out.

A certain Mr. Jones slyly interjects:

There is a lot at stake in Coachella Valley today in grapefruit and the future of the Coachella Valley grapefruit is in the hands of a great deal more man-acreage than in Imperial.

Two years later, a pair of geographers transmit the writing on the wall:

Grapefruit, although the Valley’s most important fruit crop, have a total local value of less than five hundred thousand dollars a year.

Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin.

This was

the

grapefruit county in the thirties, said Claude Finnell, whose tenure as Imperial County Agriculture Commissioner lasted for thirty-three years. He was an energetic old gentleman when I interviewed him in 2004.

Right after World War II, he said, there was a big influx of fruit in San Joaquin and Arizona and so forth.

258

Grapefruit is a good crop but it doesn’t make you much money. Used to be, the government used to buy grapefruit juice and give it out to the schools. We have a lot of salt here in the water, and after grapefruits get ten or fifteen years old, they start reacting to the salt. Grapefruit is easily frozen in the wintertime, and that’s why it’s better in Coachella, since they’re a little warmer than we are. So the tree crops just kinda pooped away.

And the date crops?

Same thing, he said with a smile. Soils and salts.

In 2003, grapefruits finally become as famous as cherry-lipped Barbara Worth, which is to say that they make the front page of the

New York Times

! It’s a three-million-dollar advertising attack, meant to addict twenty-one- to forty-nine-year-old human females to “Sass in a Glass.” Desperate times, desperate measures: American grapefruit consumption has declined by one-third between 1998 and 2001. On the other hand, since 2002 we are now selling more grapefruit to Japan than to the U.S. Japanese ladies even buy grapefruit-scented pantyhose.

All this, by the way, has mainly to do with Florida. Here’s Imperial’s minuscule part:

Texas and California produce grapefruit, too, although far less than Florida.

WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

In 2005, Imperial County will send to market four hundred and eighty-five thousand, five hundred tons of Valencias, which is to say six hundred and nineteen thousand dollars’ worth. (The number of tangerines will be comparable.) In the list of Imperial’s top forty crops, lemons are number twenty-three, grapefruits are thirty-three, and miscellaneous citrus (mandarins, tangelos and sour orange) barely makes number forty.

Well, does Imperial produce more oranges in 2005 than in 1925? I wish I could answer that. But over her citrus century, units of measurement change from trees to acres to carloads to tons. I have cynically wondered whether these alterations were intentional obfuscations, orchestrated by boosters with the aim of concealing output declines. When I think of Imperial Valley citrus, only the Bard Subdistrict comes to mind—although there, I must say, it is difficult to resist buying a cardboard box that is fat with blood oranges.

A 2004 number of the

Imperial White Sheet

hawks

FRESH CITRUS,

Tangelos 5 for $1. Grapefruit 4 for $1. Lemons 6 for $1

. On the Coachella side of the entity I call Imperial, near the northwest shore of the Salton Sea, and then again in Bard, whenever I want to I can take in the

grapefruit light

of Imperial, which, strange as it may seem, I’ve also experienced in the vicinity of yellow facades on the hottest midmornings of a Russian summer. In the Mexicali Valley, patchy citrusscapes survive in their own way. In another chapter I shall praise the golden treasures of Rancho Roa (a thousand orange and grapefruit trees, all glowing with fruit).—On the road to Algodones, in Ejido Morelos, there was a junkyard whose owner gave me a rusty horseshoe for good luck, and the woman I was with received a rusty iron from him; every third day he ran the water all day to keep his orange, mandarin and lemon trees alive; he was very proud of his water. Claude Finnell had said:

Grapefruit is a good crop but it doesn’t make you much money.

But the junkyard’s lord did not care about making money from his citrus. He was satisfied to admire his trees, eat some fruit and give the rest away.

Chapter 152

CALICHE (1975-2005)

O Earth with the mouth of a woman, release my strength . . .

—María Baranda, 1999

C

aliche,

said Alice Woodside. That’s when they would flood a field, and then the heat would become intense, as it will, and then you would see almost a pavement of dried dirt, and then it would crack. That’s bad for the crops. They couldn’t break through that.

Once upon a time, in 1910 or 1911, the Holtville high school girls’ basketball team gazed into Leo Hetzel’s lens. They were seven athletic young ladies all in ankle-length uniform skirts sashed at the waist. Their memory, and the wholesome Anglo Imperial of Barbara Worth, has taken on the wavering roundness of some old piece-of-eight which has been lying in the sands of Mexico since 1609. One side’s inscription wanders around a shield subdivided into zones and symbols; the other side sports an artichoke-leaf or acanthus quartered by a cross—are those prancing horses or rampant lions within? How can I say? This coin, already abraded by the centuries, becomes the merest nubbin of gold in my mind because my museum of experiences contains no analogue.

American Imperial was founded by and for the Ministry of Capital. Much of Mexican Imperial was taken over by the same, for which we can thank the Chandler Syndicate. And at first the money-fields sprouted like crazy. Many decades ago, Mr. Leo Hetzel, sleek and paunchy like a successful lizard, raises his finger at me and squeezes the shutter release of his camera, which is as large as a recoilless rifle. Imperial County’s photographer portrays himself! It’s playfully self-congratulatory; and now as I trudge the vacant lots of Niland and sit in the grass beside the sweaty, exhausted unemployed field workers of Calexico, I wonder where all the self-congratulation went. Leo Hetzel greets me from the time when

The Population Is Increasing at the rate of 40 per cent Every 24 Months.

And now what? Imperial’s population continues to increase north and south of the line; but caliche hardens over everything:

San Diego, Los Angeles, Tijuana and Ensenada want Imperial’s water. American labor laws and environmental regulations disadvantage Northside Imperial at the expense of Southside, whose campesinos increasingly find themselves working in

maquiladoras

which could move to China at any time. The family farm continues to die.

They couldn’t break through that.

In El Centro one can stroll past Holt and even past Orange. If you wish to dream agricultural dreams, then smell the night hay. For a long time you will be alone as you walk up Imperial Avenue. The swollen moon fuzzes like a dead animal’s eyes. The existence of the sad, sad Mexican whore (sadder than I think she would have been in Mexico) in the median strip of Imperial Avenue proves nothing for or against the

ejidos

or the American family farm or silver dimes exploding from the water farmers’ sprinklers. She waits for cars and trucks, hoping to be saved by the ministry of capital.

Chapter 153

IMPERIAL REPRISE (1754-2004)

What have we achieved? We have builded an empire in an unfit place.

—Edgar F. Howe and Wilbur Jay Hall, 1910

1

I

can’t help believing in people.

Well, that’s started to phase out. But they still use skimpy costumes and you see.