Imperial (111 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

1955:

This report is a compilation of the gross value of all the commodities produced in Imperial County and represents the gross F.O.B. Shipping Point values. It is not intended to show the net income to farmers, which due to lower farm prices, increased cost of labor and other materials purchased by farmers, was in most cases lower than in 1954.

1956:

This report is a compilation of the gross value of all the commodities produced . . . It is not intended to show the net income to farmers, which due to lower farm prices, increased incidence of pests and diseases, primarily curly top virus, reduced values of some crops drastically. This was offset in some measure by increased production for some commodities.

But don’t get me wrong. We’ve never been cheated out of a dollar in our lives.

The 1957 crop values are the second highest ever reported from Imperial County.

Chapter 113

CANTALOUPE ANXIETIES (1958)

S

o, concludes Mr. Frank R. Coit, if some research could be made as to how they look on the fruit stand, I think it would be a good thing—compared to oranges or peaches or something else. At the time we are shipping we have to compete with other fruits and vegetables.

He is a grower and shipper of cantaloupes, of course, and we are eavesdropping on him in this marketing order hearing in Fresno.

He complains: I have seen letters given to Paul Smith from ladies that couldn’t find a good melon—why couldn’t she find a good melon?

Replies a Dr. Braun: There is a long ways from the field to the housewife.

But Mr. Coit, fearless investigator, wants to

follow it and research it and control it from the field to the housewife.

Mr. F. J. Harkness, Jr., now gives utterance to the American dread:

overproduction.

(My parents used to tell me to finish all the frozen succotash on my plate because other little children were starving in China.) Mr. Harkness says: Most of us here on this board were talking back somewhere on the twentieth to the twenty-fifth of July there would be a lot of cantaloupes—perhaps way too many.

What can we do with them? Well, there is

cantaloupe a la mode; they can be frozen; they can be pickled; they can be worked in with salads . . .

And perhaps if we growers and shippers assess ourselves two cents per crate to finance promotion, we can sweet-talk Americans into buying more cantaloupes.

Where are all these cantaloupes coming from? Turning the page in high excitement, I expected to read:

The Imperial Valley,

which encompasses a royal seventy-five percent of the state’s spring melon acreage! But in fact our glut must be credited to the southern San Joaquin Valley. And then I remember that Imperial has suffered from mosaic disease lately; moreover, acreage has shrunk. That must mean that my favorite zone of California is afflicted by a crisis of over- or underproduction . . .

Chapter 114

THE BRACEROS (1942-1965)

... Imperial would not be the Magic Land it is today without help from across the border. Many of the vegetable and other crops of Imperial Valley, are “row crops” and require a huge lot of what is generally known as “stoop labor.” It is doubtful if anything like enough labor could be secured in the United States for this type of work.

—Elizabeth Harris, 1956

W

ell, good, said Javier Lupercio, getting ready to talk about the past. In 1958 and ’59, all around the railroad tracks here in Mexicali, there used to be a lot of people in tents just resting and living; those were the contractors, the braceros. Bosses from the United States would come and hire; they would call them by name or number, and as many people as that boss needed, he would hire.

Were there about the same number as we see now on the other side, in front of Donut Avenue?

Oh, no—more! Back in that bracero program, all the states of Mexico wanted to take advantage of that program. In one city block there would be maybe two hundred persons, since the train and bus station were there. There were a lot of cantinas. The Owl (Tecolote) was still around, and so was the Nopal, the White Hat, the Molino Rojo. They all closed down around 1975.

And Señor Lupercio nodded and smiled a trifle, remembering the Owl and the White Hat. It was hot and bright there in the park of the Child Heroes, and he licked his lips; soon he and José López from Jalisco and I would go to drink beer and praise women. But how could anything be as good as everything was in the old days, before we’d strayed closer to death?

Back then, he said, most of the people who went to work on the other side were contractors under the bracero program. The patrolling wasn’t as strict but there was constant checking and they went to the fields. If you didn’t have your permit you would get loaded into a van and taken back to the border.

And his face changed, and the good days became no longer quite so good.

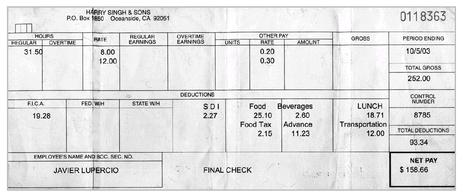

Pay stub of Javier Lupercio, purchased by WTV in 2003

But they were not all bad, either. In 1947, Don Ezekiel Pérez from Las Barrancas works as a bracero on a Montana ranch.

They treated us like family, and we sat and ate with them.

Isaías Ignacio Vázquez Pimentel remembers his bracero father in 1957.

After five months his contract ended and my dad came lighter-skinned, with his suitcase and red boots.

He brings home a dress and gives his wife his earnings.

How did it all begin? You know that—with the Chinese, and then the Japanese, then others.

Claude Finnell, the retired Imperial County Agricultural Commissioner, explained to me across his kitchen table: When people came in here to homestead, they were farming with horses. They couldn’t farm great numbers of acres because they didn’t have the power. Some of the farmers were using people from Mexico. But there weren’t many people from Mexico in the time. Mexicali was a very small town. Then they needed more and more workers. So as Mexicali filled up and ran over, so to speak, it made it easier to get those people for work. So it started during World War II. When I came here in ’54, the Mexicans were pretty well here. As I mentioned, they had houses for ’em. We were really booming in those days in terms of farming: Hay and wheat and vegetables.

So were the crickets! laughed Mrs. Finnell. Big black crickets in the street and they were singing!

Four point six million braceros stooped and sweated in Northside between 1942 and 1962. (A poster from a 2002 demonstration in Mexico City reads:

They made us strip, then fumigated us.

) Mexicali swelled with braceros and their families, waiting for the call from Northside.

We see a man in a white paper mask spraying a naked bracero with DDT. Behind them wait many other naked men in a double line. The chemical mist is white like cigarette smoke. The man who is getting sprayed (right in the face) closes his eyes and submits calmly. His penis is very conspicuous in this photo, and so is the sombrero of the man behind him.

That’s the beginning. Now for the happy ending: A Mexican leans out the window of his train, which has been chalked: BRACEROS MEXICANOS—VIVA MEXICO! He wears a long rectangular ribbon at his left lapel. It says:

BIENVENIDOS A LOS TRABAJADORES MEXICANOS.

His hair is uncombed (after all, he has been in transit for five days), and the creases at the corners of his eyes curve down, although he is young; and his lips are parted as he grips his right hand with his left hand, as if in bewilderment.

There were fifty-two thousand braceros in 1943. Four hundred and sixty-seven thousand worked the fields in the peak year 1957. After that, the numbers began to go down.

In her little restaurant south of Mexicali, Señora Socorro Rámirez said to me: When my father left here, he worked as a bracero in the U.S.—She bitterly added: He left a great ranch, with water.

And I wondered what it was that hurt so. Was it the abandonment of

her,

or the humiliation implicit in his abandonment of Mexico? Was the ranch lost forever? Did he return to his family? I flicked a glance at her smoldering eyes, and chose not to pry.

By the 1950s, braceros made up a quarter of all California farm laborers. We find, for instance, fifteen hundred of them crammed into the former San Bernardino jail, in quarters meant for a thousand, tending citrus. When forest fires broke out, they could be commandeered to fight them without extra pay.

Up in Coachella, Ray Heckman grows green corn on rented land. In 1947, he gets a hundred and twenty-five crates of corn per acre. Do you think he’s working that corn all by himself? Labor for applying water costs him seven dollars an acre (less than half the cost of the water itself, and the rent is fifty). He pays two dollars and twenty-four cents a crate for picking and packing. His total costs work out to two hundred and eighteen dollars an acre. Thank God labor is such a small proportion of these expenses! Does he employ bracero labor? At this marketing-order hearing (held in the Coachella Valley Water District Building), Mr. Heckman does not say. I guess there is a three-out-of-four chance that he doesn’t. But I’ll bet you my bandanna he’s got Mexicans working for him.

So as Mexicali filled up and ran over, so to speak, it made it easier to get those people for work.

See, in those days there was a bracero program, said Kay Brockman Bishop in Calexico. A lot of those guys came and stayed in labor camps. But you know, it was the same out here. You didn’t go to town every day.

My father had a bracero camp around eleven miles from here in the desert, said Zulema Rashid. I remember my father going over there. There were about four barracks, and they had beds, and there was the main barrack, the large one, and my Dad, he would get up at three in the morning to prepare breakfast for the braceros, and take the big pans into the fields to feed them. What did he grow? Maybe it was cotton, Bill. I don’t know. I wouldn’t remember. I saw parents of my friends losing everything they had from a bad year in cotton, and also gaining everything. Those gains and losses were mainly in Mexicali. I think I can also remember some on the U.S. side. The barracks were still there a few years back. They housed maybe three hundred braceros, all men.

(Three hundred braceros! Something tells me that Mr. Rashid owned more than the statutory hundred and sixty acres!)

C. H. Hollis, corn grower in Thermal, 1947:

I have one man that irrigates a hundred and sixty acres of grapes, corn, and alfalfa, and he does a pretty good job all by himself . . .

I wonder where that irrigator comes from?

In that same year, when Jack Kerouac went weaving through the San Joaquin Valley with his short-time Mexican girl whose

breasts stuck out straight and true,

farmers were paying three dollars for every hundred pounds of picked cotton. Kerouac went to work with a will, but could make only a dollar-fifty a day. (Border Patrolman Dan Murray:

They do work most Americans wouldn’t do.

) And Kerouac decided not to do it, either. He leaves us no descriptions of barracked braceros. Instead, he gives us

the wild streets of Fresno Mextown. Strange Chinese hung out of windows, digging the Sunday night streets; groups of Mex chicks swaggered around in slacks; mambo blasted from jukeboxes; the lights were festooned around like Halloween.

Thus the San Joaquin in 1947. In 1950 the cotton crop will be seven hundred thousand bales. But only forty-seven thousand pickers will be needed, as opposed to the hundred and twenty thousand of the boom year of 1949. Hence the Producers Cotton Oil Company advises the Farm Placement Service

to do everything possible to discourage farm workers from migrating into the San Joaquin Valley.

The Producers Cotton Oil Company seems quite altruistic! It wants only to avoid

the tragic situation where at the peak of harvest there were more unemployed cotton pickers than pickers who were working.

Wouldn’t it be just super if a grower could pick up the telephone and order forty-seven thousand cotton pickers, no more, no less? Braceros would come in handy for that. We could just count them off like other commodities.

As it just so happens, bracero agriculture is the epitome of contract labor. In this connection let me now quote our familiar companion Paul S. Taylor, writing in that bracero year 1943:

This system of labor contractors in the west began with the Chinese and continues to the present. By relieving employers of many responsibilities it has strong appeal to them; it offers some advantages to employees, finding employment and sometimes housing for them.

Happily for growers, this arrangement has nothing to do with any union, since

a contractor is an intermediary whose interest is sometimes to exploit the employer for his own advantage and possibly that of its workers and sometimes to exploit his workers for his own advantage and possibly that of the employer.

How does a contractor work? He might troll a poolhall in Sonora, or a bar he knows in Mexicali; he can avoid or even replace local labor if it’s acting uppity.

208