Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (4 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Perhaps the greatest influence on this future political powerhouse was one Stevens never escaped—a club foot that marked him in an era when many were intolerant of physical handicaps. A neighbor recalled that other boys would “laugh at him, boy-like, and mimic his limping walk,” which “rankled” young Thad. Though he ultimately stood six feet tall and developed a strong, athletic constitution, Stevens always confronted the popular superstition that his deformity was the work of the devil. Those painful early experiences helped form the future politician. Stevens’s lameness—not to mention that of his older brother, who had

two

club feet—contributed to a dark, sardonic outlook that could intimidate both friends and foes. It also led him to sympathize with underdogs, the poor, those with afflictions of any kind. A congressional colleague recalled that Stevens “seemed to feel that every wrong inflicted upon the human race was a blow struck at himself.”

Nineteenth-century America had no greater underdogs than the slaves in the South, and Stevens became both a fervent opponent of slavery and one of the least prejudiced white men in public office. As a lawyer before the war, he represented escaped slaves and opposed the slave catchers who searched for supposed fugitives. Neighbors told stories of Stevens purchasing freedom for slaves. His Lancaster home served as a stop on the Underground Railroad for blacks fleeing bondage. For his last nineteen years, Stevens’s home was maintained by Lydia Smith, a “mulatto, who in her youth had great beauty of person.” Stevens always treated her with respect, addressing her as “Mrs. Smith” and including her in social exchanges as an equal. Whispers insisted that the two were lovers. He never answered the whispers.

In the House of Representatives, Stevens’s stern will and slashing rhetoric commanded respect and won him the leadership of the Republican majority. Another Republican remembered that most legislators chose not to tangle with the Radical from Lancaster: “[M]any a new member was extinguished by his sarcastic thrusts.” An adversary recounted Stevens using a single sentence to “lay a daring antagonist sprawling on the ground…the luckless victim feeling as if he had heedlessly touched a heavily charged electric wire.” One enchanted observer granted Stevens “the very front of Jove himself. Nothing can terrify him, and nothing can turn him from his purpose.”

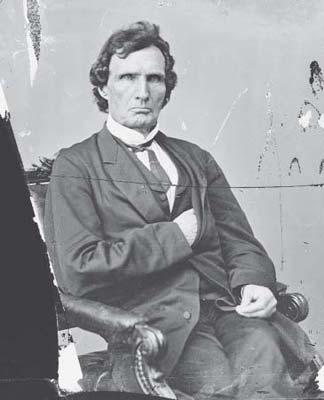

Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Radical Republican leader.

Stevens’s greatest weapon was a dry sense of humor, which struck “like lurid freaks of lightning,” launched “with a perfectly serious mien, or…a grim smile.” Walking a narrow path one day, he encountered a rival who refused to let him pass, growling, “I never stand aside for a skunk.” Giving way, Stevens replied equably, “I always do.” Advised that President Johnson was “a self-made man,” Stevens answered that he was “glad to hear it, for it relieves God Almighty of a heavy responsibility.” For one thrust, Stevens used President Lincoln as his foil. When Lincoln asked if a proposed Cabinet appointee would steal, the congressman answered, “I don’t think he would steal a red-hot stove.” Hearing of the remark, the appointee demanded a retraction. Old Thad obliged. He reminded Lincoln of his statement that the appointee would not steal a red-hot stove, then added, “I now take that back.”

Stevens could mock his own pretensions. After typhoid fever caused his hair to fall out, he wore a lush wig to conceal his baldness. One observer thought Stevens wore the hairpiece so haphazardly that it was “at the first glance recognized as such.” A female admirer evidently missed the telltale signs and requested a lock of the congressman’s hair. Ever gallant, Stevens yanked off the wig and offered her all of it.

By mid-May of 1865, Stevens was troubled that Johnson had recognized the “restored” government of Virginia, which was created during the war but existed mostly as an idea, not a reality. The Pennsylvanian insisted that only Congress could reconstruct the Southern states. In response to the president’s proclamation on Virginia, Stevens delivered a letter that made no pretense to courtesy. Johnson’s action was “beyond my comprehension,” he wrote, “and may provoke a

smile

, but can hardly satisfy the judg[men]t of thinking people.” Stevens advised Johnson to call Congress into session to address the question. Otherwise, many would “think that the executive was approaching usurpation.” Icily, Johnson made no reply to the leading figure in the House of Representatives.

Seven weeks later, Stevens sent another letter to the president. Following the model set in his North Carolina proclamation, Johnson was appointing governors for each Southern state, instructing them to call conventions to write new state constitutions. Then, Johnson intended, the Southern states could resume their places in the national government. Admitting to “a candor to which men in high places are seldom accustomed,” Stevens came straight to the point: “Among all the leading Union men of the North with whom I have had intercourse, I do not find one who approves of your policy…[which] will greatly injure the country.” Like Stevens’s earlier letter, this one asked Johnson to wait for congressional action. Once more, Johnson did not deign to reply.

For the other Southern states, the president issued proclamations like the one for North Carolina. Nurtured by Johnson, the seceded states wrote new constitutions, formed new governments, and chose congressmen and senators to send to Washington. Behind the scenes, Johnson advised Southerners to follow a moderate course and not restore former Confederates to power, but these were mere suggestions. For Johnson, the states must choose their own way. According to the newly appointed governor of South Carolina, the president asked only “that I write him occasionally and let him know how I was getting on in reconstructing the state.” Johnson’s designee as governor of Virginia complained that on critical issues he could get neither instruction nor advice from the president.

Instead of reconstructed Southern states led by men committed to the Union, Johnson spawned resurrected Confederate governments that bristled with former rebels in high office. The new Southern governments embarrassed the president who so recently demanded the punishment of traitors, yet Johnson made no public objection. The sovereign states, for him, could do as they wished.

Two features of the new Southern state governments threatened immediate trouble for Johnson. The first was the nature of the men chosen to serve as congressmen and senators from the seceded states. Most, according to a congressional report in 1866, were “notorious and unpardoned rebels, men who could not take the prescribed oath of office, and who made no secret of their hostility to the government and the people of the United States.” They included ten former Confederate generals and five more army officers of lower rank, seven former members of the Confederate Congress, and three men who were members of conventions that voted to secede in 1861. That many of the new state officials had initially opposed secession in 1861 and reluctantly followed their states into rebellion—traits that may have made them moderates in the eyes of other Southerners—made no difference to Northerners who were outraged by the specter of “unrepentant secessionists” in the halls of Congress. Having started and fought a war that cost hundreds of thousands of Northern lives, these former Confederates proposed to take the reins of power in the national government they had attacked with vast armies. The presence of such men in Washington City, one congressional leader recalled, “inflamed” Northern congressmen, driving many “to act from anger.”

Johnson knew that the Southern states were following a reckless and arrogant course, but he would defend to the death their right to do so. He wrote anxiously to the provisional governor of Georgia after learning that all of that state’s new congressmen had been so involved in the Confederate cause that none could take the oath of office required for Congress. One of Georgia’s new senators was Alexander H. Stephens, who had been vice president of the Confederacy and was then under indictment for treason. Stephens’s selection, Johnson wrote privately, was “exceedingly impolitic.” Yet the president made no public objection to the Southerners’ choices.

Equally incendiary, the restored Confederate governments began to adopt “black codes” that “practically deprived the negro of every trace of liberty.” One Republican called them “a striking embodiment of the idea that although the former owner has lost his individual right of property in the former slave, ‘the blacks at large belong to the whites at large.’” Though specific terms varied from state to state, the pattern was for “[t]hat which was no offense in a white man [to be] a heinous crime, if committed by a negro.” Vagrancy laws allowed the arrest of idle blacks, who would be put to work by local governments or loaned out to private employers—in short, a straightforward restoration of slavery. Blacks were denied the right to serve on juries, to testify in court, to own property. These “Johnson governments” certainly would never allow the freedmen to vote. Johnson raised no objection to the black codes, either.

The president’s silence on these Southern actions told Southern whites that he was on their side. In a Mississippi hotel, one confided that Johnson “don’t believe much in the niggers, neither, and when we’re admitted into Congress we’re all right.” Beginning in late May of 1865, when Johnson announced the terms for North Carolina’s new government, white Southerners came to expect the president would help them restore much of their former lives. According to one traveler, men in the South “quoted the North Carolina proclamation, and thanked God that there had suddenly been found some sort of breakwater against Northern fanaticism.” By the end of 1865, a Northerner traveling in the South found that whites assumed “that the President had gone over to the so-called Democratic party, and would use the whole power of his office to break down the so-called Black Republicans.” Northerners began to fret, in the words of Radical Ben Wade of Ohio, that Johnson was dissipating “the whole moral effect of our victories over the rebellion,” while “the golden opportunity for humiliating and destroying the influence of the Southern aristocracy has gone forever.”

This fear grew as the president implemented his program for granting amnesty to Southerners who took up arms. Johnson’s amnesty program did not include several categories of rebels, notably those owning taxable property worth more than $20,000. Those rich Southerners would have to beg the president for their pardons. The grandees who had snubbed the former tailor’s apprentice for decades would have to seek mercy from President Andrew Johnson. They did so in droves. For months during the second half of 1865, the White House was clogged with wealthy Southerners, hat in hand, asking for their pardons.

Initially the pardon program seemed to express Johnson’s resentment of the Southern aristocracy, forcing the rich to crawl to him for dispensation. His lifelong class hostility was captured in the jibe that “[i]f Andy Johnson were a snake, he would hide in the grass and bite the heels of rich men’s children.” But Northerners came to detest the pardon process, fearing that Johnson was being seduced by those who solicited his favor. Not only were the former rebels getting their pardons, but they also were tying the president ever more closely to the traditional Southern power structure. “They kept the Southern President surrounded by an atmosphere of Southern geniality,” complained one New England reporter, “Southern prejudices, Southern aspirations.” With a heavy daily diet of Southern visitors, Johnson “heard little else, was given time to think little else.” By 1866, Johnson had granted individual pardons to more than 7,000 Southerners.

As the days of 1865 grew shorter, Johnson’s honeymoon period as president was drawing to a close. With no Congress to inhibit him, he had swiftly reconstituted Southern state governments, ignoring the views of Republicans like Stevens. But the Republicans were coming. Soon they would arrive in Washington City with the overwhelming majorities they won in the 1864 election: 42 to 10 in the Senate, and 149 to 42 in the House. To avoid a challenge from these powerful Republicans, Johnson would have to demonstrate that his policy had succeeded, that his efforts—often called “presidential reconstruction”—were restoring justice and prosperity. Though no policy could have achieved those goals so quickly, the violence and poverty that oppressed the South would galvanize the opposition to Johnson.

NOVEMBER 1865

Nothing renders society more restless than…a revolution but half accomplished.

C

ARL

S

CHURZ,

1865

T

HE SCARS OF

civil war ran fresh and deep across the land. In the North, the sacrifice of men and treasure had been appalling. An estimated 360,000 Union troops died of all causes. The towns and roads seemed littered with amputees, soldiers who survived the brutal medical practices of the age, constant reminders of the war’s murderous price. But the North had won, and few battles had been waged on its soil. Through the northern and western states, 23 million people gathered themselves for a burst of economic expansion that would transform the continent. The industrial energy devoted to wartime production would be directed to building railroads to connect the Atlantic with the Pacific.

In the South, the human losses—260,000 soldiers dead—were a greater proportion of the population, while the physical wreckage was far worse. Nine million Southern whites and four million freed slaves faced fearsome challenges. Travelers were staggered by the destruction and poverty.

In Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, a visitor saw neither fences nor crops. Northern Virginia showed few signs of human industry, only an occasional wan, half-cultivated field. In Richmond and in Columbia, South Carolina, chimneys stood forlornly, surrounded by ash, blackened walls, and piles of bricks. Some shops had goods, but no one had money to buy them. Atlanta had burned also, leaving both races homeless. Blacks and whites lived in makeshift shelters on the edge of town, in clusters that looked like “fantastic encampment[s] of gypsies or Indians.” Young men were scarce in Charleston, birthplace of secession, which had become

A city of ruins, of desolation, of vacant houses, of widowed women, of rotting wharves, of deserted warehouses, of weed-wild gardens, of miles of grass-grown streets, of acres of pitiful and voiceful barrenness.

The Southern economy stood still. For slave owners, emancipation represented a massive loss of capital. According to a calculation prepared for Johnson, the South lost roughly 30 percent of its wealth when the slaves walked away from its plantations. As economic activity dwindled, whites and blacks faced idleness. In one town, “People on Main Street sat out on the sidewalks gossiping and smoking, some with tables playing chess, backgammon and cards. As the sun moved they moved from one side of the street to the other to get the shade.”

For all the travail of daily life, a single sea change became the focus of political and social energy in the South. Four million blacks—almost one-third of the people in the region—were now free. Whites and blacks would have to work out what that freedom was, a process that was bound to be painful. By far the greater share of pain would be felt by the impoverished, unschooled, and weaponless freedmen. Most owned only the clothes on their backs. Somehow they had to provide for themselves in a hostile land. But for whites, too, emancipation brought upheaval.

Most Southern whites rejected any suggestion that the freed people could be equal to them. A visiting writer concluded that Southerners viewed the former slave as “an animal; a higher sort of animal, to be sure, than the dog or the horse, but, after all, an animal.” Political rights for the former slaves, such as voting, seemed “the most revolting of all possibilities…[a] degradation upon a gallant people.”

The changes brought by emancipation reached into every human interaction. How should a free black person address a white person? How could he or she walk on the street? Should a black step aside for whites? What if a white person acted improperly? Could a freedman object? The freed slaves wanted to act as equals. Whites were shocked. As one visitor observed, they “perceive[d] insolence in a tone, a glance, a gesture, a failure to yield enough by two or three inches in meeting on the sidewalk.”

First came the simple act of traveling through the countryside. Blacks, in theory at least, now could come and go as they pleased, could walk the roads at any time of the day or night. In the early postwar months, and to the dismay of Southern whites, many freed slaves did just that. A Northern traveler reported that “the highroads and by-ways were alive with footloose colored people.” Some searched for family members who had been sold or carried into other states. Some fled angry masters or sought better work. Some longed to see what was on the other side of the hill. A black waiter explained the phenomenon: “You know how a bird that has been long in a cage will act when the door is opened; he make a curious fluttering for a little while. It was just so with the colored people. They didn’t know at first what to do with themselves. But they got sobered pretty soon.”

The overthrow of slavery forced a shift to new labor arrangements. Often the results were harsh. Some freedmen were “turned off” farms where they had lived and worked for years. The owners did not care to pay them, or had no money to do so, so they sent them away. Some masters did not tell their slaves of emancipation, keeping them in bondage for months beyond the war’s end. The transition to paying for labor was tortuous. The former slaves had little bargaining power. Most knew only farm work yet had no land of their own. Without experience in making contracts for wages, many entered into yearlong contracts at rock-bottom wages, or for a share of the crop. Mississippi required proof every January that each freedman had a labor contract for the coming year. Some worked an entire year only then to be driven off the land, unpaid. Blacks who violated their contracts faced imprisonment and involuntary, unpaid labor. As one Northern correspondent summarized it, the “black codes” adopted by Johnson’s state governments allowed the states to “call them freedmen, but indirectly make them slaves again.”

Conflicts flared when the former masters used physical force against their workers, as they were accustomed to do. Most whites thought it impossible that blacks would work without coercion. A Virginian acknowledged that “[a] good many of the masters forget pretty often that their niggers are free, and take a stick to them, or give them a cuff with the fist.”

Southern whites responded to emancipation in complicated, sometimes contradictory ways. Many, believing that the freed people could never provide for themselves, predicted that they would simply die out. One South Carolinian insisted that “being left to stand or fall alone in a competitive struggle for life with a superior race, [the freedmen] would be sure to perish.” Abolitionists, he gloated, “would find they had exterminated the species.” But the freed slaves did not disappear. Indeed, many government records show that more whites than blacks took advantage of postwar food handouts.

Some whites embraced the fanciful notion of sending the blacks someplace else—Africa, Texas, Peru, the Sandwich Islands, any place but where they were. Then, the whites argued, Southern fields could be worked by industrious German immigrants. Problems quickly emerged with this solution: there was neither transportation for four million freed slaves, nor a place to send them, nor any significant interest among the freedmen in leaving.

The whites’ refrain turned to the need to “keep the nigger in his place.” A North Carolinian explained in the fall of 1865 that he would vote for political candidates who promised to do just that: “If we let a nigger git equal with us, the next thing we know he’ll be ahead of us.”

Racial violence spread. White assaults on blacks erupted during the commonplaces of daily life. If freed slaves did not touch their hats to their former masters, they were saucy, unendurable. Whites railed when Negroes resisted beatings, seeing resistance as insubordination. One Southerner swore that “nothing would make me cut a nigger’s throat from ear to ear so quick as having him set up his impudent face to tell that a thing wasn’t so when I said it was so.” A New York correspondent wrote that “half-a-dozen times, in the course of a single day, I observed quarrels going on between negroes and white men.”

The violence overwhelmed the peacemaking efforts of officials of the Freedmen’s Bureau, established by Congress in March 1865 to aid both whites displaced by the war and former slaves making the transition to freedom. Thinly sprinkled through the region, Bureau agents were supposed to secure fair treatment for the freedmen and prevent the reintroduction of slavery under another name. Many Bureau agents were startled by racial attacks they could not restrain. In his first ten days in Greensboro, North Carolina, a Bureau agent received two cases of whites shooting blacks. “The fact is,” he explained, “it’s the first notion with a great many of these people, if a Negro says anything or does anything that they don’t like, to take a gun and put a bullet into him.” In the interior of South Carolina, a monthly Bureau report recorded the whipping of a freedman and his children while tied to stakes, the whipping of another who also received a knife wound to the face, and the beating and unexplained disappearance of a freedwoman. A group of North Carolina whites went on a “spree,” whipping pro-Union whites, castrating and murdering a black man, then shooting other blacks, including two young boys. In Columbia, South Carolina, a correspondent reported the shooting of a Negro “as if he had been only a dog,—shot at from the door of a store, and at midday!” When a black mistakenly cut down a tree on a white man’s farm in Virginia, the white man “deliberately shot him as he would shoot a bird.”

In the summer of 1865, President Johnson sent Carl Schurz, an ambitious German-American politician, to examine conditions in the South. Schurz’s report was chilling:

I saw in various hospitals negroes, women as well as men, whose ears had been cut off or whose bodies were slashed with knives or bruised with whips, or bludgeons, or punctured with shot wounds. Dead negroes were found in considerable number in the country roads or on the fields, shot to death, or strung on the limbs of trees. In many districts the colored people were in a panic of fright, and the whites in an almost insane state of irritation against them.

Another presidential agent placed the blame on the Southern state governments nurtured by Johnson. In South Carolina, he reported, Johnson’s appointed governor had “put on their legs a set of men who…like the Bourbons have learned nothing and forgotten nothing.”

By 1866, the violence would become organized. Southern whites formed terrorist groups with chivalric names—the Knights of the Golden Circle, the Knights of the White Camellia, the Teutonic Knights, the Sons of Washington, the Knights of the Rising Sun, and the Ku Klux Klan. As many as a hundred masked and hooded riders could descend on a homestead or town, killing and maiming at will.

The Southern violence turned Northern observers into cynics. “[T]o knock [a Negro] down with a club,” wrote a New Englander, “or tie one of them up and horsewhip him, seems to be regarded as only a pleasant pastime.” A stableman in South Carolina, he added, “cut off a negro boy’s ear last week with one blow of a whip, and tells of the act as though it were a good joke.”

The assailants rarely faced punishment from state or local authorities. In South Carolina, a white killed a black man who was stealing corn. He was tried and exonerated. An ex-Confederate official told of a white man in Texas who whipped his former slave woman for insolence; when the woman’s husband protested, the former master shot him. The wounded husband was jailed for assault; the former master went free. A Freedmen’s Bureau report for South Carolina explained that “it is difficult to reach the murderers of colored people, as they hide themselves and are screened by their neighbors.” A Bureau agent in North Carolina told Congress that he knew of many murders of blacks by whites; in none were charges brought. A Union general posted to Mississippi in 1865 and 1866 testified, “Murder was quite a frequent affair against freedmen everywhere in that community, and the commission of crimes of a lesser grade was still more frequent.” He knew of no occasion when a white was punished for an offense against a freedman.

At the end of 1865, General Grant asked army commanders in the South to report on the violence. Commanders in only five states responded (the Carolinas, Mississippi, Georgia, and Tennessee). They described more than 200 assaults on blacks and 44 murders. Much of the violence, however, went unreported. No estimate of the murders and violence in the South after the war is entirely reliable, but the numbers were consistently dreadful.

The carnage was worst in Texas, with its huge distances and wild frontiers. By 1868, an army commander reported that “the murder of negroes is so common as to render it impossible to keep accurate count of them.” The records of the Freedmen’s Bureau yield a dispiriting catalog of reasons for the murders of black Texans in the postwar years:

[The] freedman did not remove his hat when he passed [a white man], negro would not allow himself to be whipped; freedman would not allow his wife to be whipped by a white man; he [the victim] was carrying a letter to a Freedmen’s Bureau official; kill negroes to see them kick; wanted to thin out niggers a little; didn’t hand over his money quick enough; wouldn’t give up his whiskey flask.

In 1865 and 1866, more than 500 whites were indicted in Texas for murdering blacks; none was convicted. During the 1868 election campaign, an estimated 2,000 Negroes were murdered in Texas.

A bureau agent in Mississippi captured the lawlessness of that time and place:

Men, who are honorable in their dealings with their white neighbors, will cheat a negro without feeling a single twinge of their honor; to kill a negro they do not deem murder; to debauch a negro woman they do not think fornication; to take property away from a negro they do not deem robbery….

While the president worked to return Southern state governments to the former rebels, the army drew the impossible assignment of keeping a lid on the region’s cauldron of race hatred. At the end of the war, no institution enjoyed as much stature in the North as the army. After Lincoln’s death, no individual could rival the prestige of General-in-Chief Ulysses Grant. Still, both the army and Grant were ill suited to the task of governing more than one-third of the country. The army shrank quickly after the Confederate surrender in April 1865, from 1 million men to fewer than 50,000. Thousands of federal troops remained in the South to keep the peace—enough soldiers to enrage white Southerners, yet not enough to protect the freedmen. Even more galling to Southern whites, many of those soldiers were blacks, former slaves. Without homes or employment to return to, colored troops were willing to remain in uniform. In September 1865, the army commander in Mississippi had thirteen infantry regiments; twelve were black.