Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (32 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Trumbull of Illinois and Grimes of Iowa stressed how much they disliked Johnson. “If the question was, is Andrew Johnson a fit person for President?” Trumbull wrote, “I should answer,

no

.” He adopted the argument of Judge Curtis: he could not remove the president for misconstruing a doubtful statute, the Tenure of Office Act. Grimes called the incumbent “an unacceptable president,” but insisted that he would not disrupt the “harmonious working of the Constitution” to get rid of him. Fessenden of Maine coolly analyzed each impeachment article, stumbling slightly over Article XI. Impeachment, he concluded, should be used only “in extreme cases, and then only upon clear and unquestionable grounds” that raise “no suspicion upon the motives of those who inflict the penalty.” Henderson’s explanation also struggled briefly with Article XI, the one on which he had promised to vote for conviction only four days before the final ballot.

The explanation filed by Senator Peter Van Winkle embraced a range of hair-splitting niggles. He objected that the firing of Stanton did not violate the Tenure of Office Act because the articles failed to state that Stanton actually received the removal order from the president. As to the appointment of Adjutant General Thomas, Van Winkle triumphantly pointed out that the word “appoint” appeared nowhere in the president’s letter designating Thomas as Stanton’s successor. Therefore, the West Virginian concluded, the designation was not an appointment “in the strict legal sense of the term.” Van Winkle did not explain what Johnson had done other than appoint Thomas. Finally, the senator denied that the president prevented the execution of the laws, as charged in Article XI. Johnson, he said, merely devised a plan to do so, a mere “mental operation.”

Van Winkle was one of the targets of a countervailing eruption from Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner against the “technicalities and quibbles” arrayed in the president’s defense. Calling them “parasitic insects, like vermin gendered in a lion’s mane,” the disappointed Radical challenged history for an instance of “equal absurdity in legal pretension.”

An explanatory letter from Tennessee’s Fowler appeared several weeks later. Decrying the impeachment effort as a “scheme to usurp my Government,” Fowler insisted, “I acted for my country, and have done what I regard as a good act.”

In a letter to his wife, Ross predicted that the nation would thank him: “Millions of men are cursing me today, but they will bless me tomorrow.” In remarks in the Senate on May 27, he admitted he had changed his mind before casting his impeachment vote, asking, “Who among you…was at all times free from doubt?” He had been singled out, Ross charged, as the “scapegoat for the egregious blunders, weaknesses, and hates which have characterized this whole impeachment movement, itself a stupendous blunder.” He denied that his vote reflected any improper influence.

Though the seven defectors have ever since received credit, or blame, for thwarting the first presidential impeachment, they may not have been Johnson’s last line of defense. Substantial evidence suggests that the president had in his vest pocket several other Republican senators who would have voted for acquittal if their votes were needed. An ally of the Astor House group, New York broker Ralph Newton, telegrammed Collector Smythe a few hours after the vote, “Twenty-two were sure on other articles, and twenty-one on that [Article XI] if necessary.” Sam Ward made the same claim. The

Chicago Tribune

reported that Johnson’s advocates claimed they had at least four more votes if they needed them. Over the next years, reports named several senators as having been willing to support acquittal in a pinch: Waitman Willey of West Virginia, William Sprague of Rhode Island, Edwin Morgan of New York, and James Nye of Nevada. The listing of Nye, a former New Yorker with ties to Thurlow Weed, is intriguing; he was one of the senators listed by postal agent James Legate when he offered to sell votes to Edmund Cooper.

There could have been others. On the day after the vote, Johnson expressed surprise that an Oregon senator did not vote for him. That man, the president explained, had “financial relations” with Treasury Secretary McCulloch and had said he would vote as McCulloch directed. The president blamed McCulloch for not giving the senator proper direction. Johnson also had expected to win the vote of Rhode Island’s Henry Anthony.

Only nineteen votes, though, were needed. Despite the speculation about other senators, only the seven who did vote for acquittal would be the principal targets of Butler’s investigation into corruption. No matter what the Senate thought or the nation wished, the impeachment saga would not be over until Ben Butler said it was.

MAY 17–JULY 5, 1868

People here [in Washington] are afraid to write letters, and I must be a little cautious at present. Spies are, really, everywhere.

J

EROME

S

TILLSON

t

O

S

AMUEL

B

ARLOW,

M

AY

22, 1868

P

ARTS OF BUTLER’S

investigation started while the trial was still going on. As the Senate received evidence, Butler’s agents reported to him about suspicious characters and shady conversations. He knew about printer Cornelius Wendell, the architect of the president’s acquittal fund. Thurlow Weed’s minions had been in Washington City for weeks, so the New York boss was high on Butler’s list, along with Sheridan Shook, Sam Ward, and Collector Henry Smythe. Butler knew about the corrupt Perry Fuller and his hold over Edmund Ross—that cried out for a closer look. Missouri Senator John Henderson’s erratic course certainly seemed fishy. And then there was the Whiskey Ring, America’s political bogeyman, and its lawyer, Charles Woolley. Equally important, Butler knew the subjects he had to keep concealed. It would not do to reveal some of his own activities, or those of his allies.

Tips poured in from around the country. What about the doctor from Paterson, New Jersey, who claimed he was in the president’s bedroom when Woolley revealed a $20,000 payment for Ross’s vote? Another source claimed that Ross received $150,000. A New Hampshire man was convinced that a cousin of Ross’s delivered bribe money to the Kansas senator. The niece of General Alonzo Adams pleaded for an investigation of her uncle and his boast that he bought senators’ votes for the verdict. Volunteer informants urged Butler to question an honest revenue agent in Chicago who could reveal all. What about the businessman in Troy, New York, who supposedly sent $100,000 to aid the president, or Vinnie Ream with her female charms, or a former army colonel with ties to the Whiskey Ring, or a tax collector who gave 10-to-1 odds that Johnson would be acquitted?

Butler’s most prolific source of leads was a raffish New Yorker, George Wilkes, who published the scandalmongering

National Police Gazette

, a crime magazine. Sometimes accused of blackmailing the subjects of his stories, Wilkes only once was convicted of criminal libel. He turned that jail sentence into profit by publishing an exposé of the prison system. Wilkes sponsored prizefights and acquired a sporting weekly,

Spirit of the Times

. Politically, he became a Radical Republican during the war, then joined Butler in a scheme to colonize Baja California. Avid for impeachment, Wilkes shared with Butler his expertise in the world of detectives and law enforcement. Wilkes and Butler were accused of keeping the doubtful senators under twenty-four-hour surveillance for the week before the vote on May 16. Wilkes was on the Senate floor several times during May, engaging in informal advocacy with individual senators. Like many sporting men of the day, the New Yorker bet heavily on the trial’s outcome.

Wilkes developed a confidential informant who was close to Sam Ward. According to this source, Ward paid Senator Ross $12,000 for his vote. The money supposedly came from John Morrissey, the prizefighter-turned-congressman who ran both Tammany Hall and New York’s biggest lottery business, and also was one of Sam Ward’s clients. In a salacious twist, Wilkes speculated that the payoffs were handled by “Charley Morgan,” Sam Ward’s cross-dressing mistress who supposedly was having a simultaneous affair with Congressman Morrissey’s wife. Charley Morgan, Wilkes pointed out, “has the singular advantage of being able to change himself into a handsome young woman for one purpose or another.”

In the middle of Butler’s investigation, the young woman posing as Charley Morgan was arrested in New York. Identified in the

New York Times

as “Julia H,” she pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor of “indecency,” telling the court that she had not worn women’s clothes for four years. Butler assured Sam Ward that he had nothing to do with Morgan’s arrest, protesting that he had resisted pressure to “mortify” Ward by calling her as a witness. Butler never proved that Sam Ward had bribed Senator Ross.

The impeachment committee took testimony for six weeks after the vote on May 16. While the committee made its inquiries, workmen replaced the heavy carpets of the Capitol with white matting for the heat of summer; they retired cushioned chairs in favor of wooden ones. The committee—which soon shrank to Butler and John Logan of Illinois, with only Butler present on some days—heard over a dozen witnesses, several for more than one day. Four members of the Astor House group appeared: Weed, Shook, Erastus Webster, and Woolley. Butler questioned Treasury official Edmund Cooper, New York Collector Henry Smythe, Indian trader Perry Fuller, railroad man James Craig, and Sam Ward. Although it offended the dignity of the Senate to be investigated in this way, two senators agreed to testify. Missouri’s Henderson appeared early in the investigation, while Pomeroy of Kansas testified four times in a frantic effort to straighten out his crooked story.

From the first day of the investigation, Butler zeroed in on Woolley, the Whiskey Ring lawyer. Butler may have understood that he could only get so far with wily political alligators like Thurlow Weed and Cornelius Wendell. They gave the testimony they intended to give, no more and no less. They did not get embarrassed or flustered. Weed, for example, admitted to having conversations about bribing senators and receiving numerous coded telegrams following up on those conversations. When pressed for details, the New York boss lamely insisted that he knew only that the messages “related to impeachment,” but did not recall what they meant—even though all of the events had occurred within the previous two weeks! In another notable exchange, Butler began to abuse Wendell for refusing to answer a question. “If I tell anything,” Wendell responded coolly, “I shall tell all I know. Do you wish me to do so, General?” Butler, acutely aware of his own attempt to pay $100,000 for Wendell’s testimony against the Astor House group, changed the subject.

Butler did not back down with Charles Woolley, the Whiskey Ring lawyer who handled large piles of cash during the last two weeks before the vote. Through two committee appearances, Woolley used evasions, objections, assertions of the attorney-client privilege, and other delaying tactics. The committee tried to “follow the money” in Woolley’s possession—employing the tactic that became a mantra in the Watergate investigation a century later—particularly Woolley’s withdrawal of $20,000 from a Washington bank during the trial. Where had the money gone? The next day, Woolley argued that his prior testimony was void because he took the oath from a mere committee member, not from the nominal committee chairman, John Bingham. After hours of testifying, Woolley claimed he gave most of the money ($16,000) to his hotel suite-mate, Sheridan Shook, for safekeeping. The rest, according to Woolley, went for high living. Unfortunately for Woolley, Shook denied receiving any money from him.

When Woolley was summoned for a third day of testimony, the Whiskey Ring lawyer lost his appetite for the process. First he pled illness, providing a letter from a physician who said Woolley could not leave his hotel because of “irritation from sequellae of gastric derangement.” Woolley accompanied that message with an affidavit challenging the committee’s power to seize his papers or ask him about his private business. Miraculously recovering his strength, he fled to New York. Stalling was a shrewd tactic. Butler was under impossible time pressure. The second round of voting on the impeachment articles was scheduled for May 26. If the corruption investigation were to make any difference in the outcome, Butler needed results before then. Only Butler signed the committee’s interim report, which issued on May 25. That report admitted there was no proof yet of corruption in the Senate’s vote but demanded that the House compel Woolley’s testimony.

On the evening of May 25, the sergeant-at-arms of the House seized Woolley, who had returned to Washington. Hauled before the House the next day, Woolley had to explain why he would not answer the committee’s questions. The proceeding was interrupted so the congressmen could trudge to the other side of the Capitol to witness the death rattle of the impeachment case: the Senate’s acquittal of Johnson on Articles II and III. Reconvening, the House ordered Woolley to answer the committee’s questions. Protesting that he had not tried to corrupt any senators, Woolley told the House he would not answer questions about actions unrelated to the trial. The House found him in contempt and authorized the sergeant-at-arms to detain him until he testified. Woolley was held in the hearing room of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, which was fitted out with a bed. Meals came from the Capitol restaurant.

The jailing of Woolley was a sensation. Democrats flocked to see the new celebrity, who passed the time in his elegant prison with his wife and child. House Democrats staged confrontations over Butler’s high-handed tactics. As the lawyer’s detention dragged on, he was moved to the studio of Vinnie Ream in the Capitol basement. She was forced to shift her sculptures into the corridor.

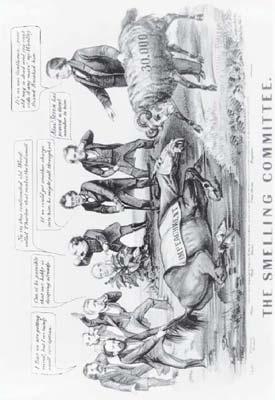

“The Smelling Committee” meets Johnson and his “Woolley Friend” after the trial.

While Woolley battled Butler, his Astor House allies scrambled to back him up on the unexplained $20,000. Another Seward intimate, who served as the secretary of state’s agent in several matters, stepped forward with an unlikely alibi. After the committee first questioned Woolley about the money, Cornelius Wendell and Woolley’s new alibi witness took the noon train to New York, polishing a story through nine hours of jostling over the tracks. They met Sheridan Shook late that evening (May 20) at the Astor House, whereupon the alibi witness pulled a wad of currency out of a pocket and claimed it was Woolley’s money. Or so Wendell testified.

The alibi witness, who carried the aristocratic name of Ransom Van Valkenburg, told Butler’s committee that on May 17 (the day after the first impeachment vote) he and Woolley made a $10,000 bet on the 1868 election. The bettors supposedly asked Shook to hold the stakes, but Shook refused. Portraying Shook and Woolley as blind drunk at the time, Van Valkenburg said he picked up Woolley’s money and placed it in the safe at the Metropolitan Hotel, where it remained undisturbed for three weeks. In one of the most convincing passages in his final report, Butler wrote, “[Y]our committee believed no part of this stupid fabrication.”

The committee questioned the imprisoned Woolley on May 27, after his first day under arrest, rejecting his request for a lawyer. Finding the lawyer still unresponsive, Butler sent Woolley back to his detention. However much Woolley might dislike being detained, Butler was the one who could not wait. Eleven days later, Woolley managed to place his dilemma before the House. This time, Woolley assured the House that he would answer Butler’s questions. Butler accepted those empty assurances. The committee brought in Van Valkenburg, who produced a package of greenbacks totaling $17,000 and a hotel manager who said the package had, indeed, been in his hotel safe. Stymied by this “mass of corruption,” unable to distinguish Van Valkenburg’s cash from any other cash Woolley may have had, Butler released the Cincinnati lawyer after seventeen days of confinement.

Butler had other leads. He brandished a statement by seven congressmen that in January 1868, Senator Fowler of Tennessee demanded the impeachment of President Johnson to end “the sufferings of Southern Union men and the murder of so many of them.” Butler recited other examples of Fowler’s previous support for impeachment. What, he demanded, converted the Tennessean to a key vote for acquittal? John Bingham and the governor of Tennessee were certain Fowler had been bribed. And what about Henderson of Missouri and his mystifying changes in position? In each case, Butler could not get his hands on definitive proof of bribery.

Butler got closer with Senator Ross and his sponsor, Indian trader Perry Fuller. Fuller admitted that he offered $40,000 to Senator Pomeroy’s brother-in-law Willis Gaylord for the “Chase movement,” and that he did so on the authority of Edmund Cooper at Treasury, the president’s devoted supporter. Even more damning, Fuller acknowledged that in late May, in the midst of Butler’s investigation, he paid off the home mortgage of James Legate, the Kansas postal agent who had spilled the beans about Fuller’s involvement in vote-buying. Fuller also arranged for Legate to collect pay from the Post Office for his many weeks of scheming in Washington and then paid for Legate’s passage back to Kansas. In return, Legate gave Fuller all his papers about the bribery scheme, which Fuller promptly incinerated. The Indian trader’s purpose in all these steps, he admitted, was “drying up the investigation.” Despite the sinister implications of these deeds, Butler did not uncover the final link, the one that traced Cooper’s cash to the pocket of a senator.

In at least one instance, Butler seems to have missed key evidence. After a two-hour appearance before the committee, Sam Ward, the King of the Lobby, shared his fine cigars with the House manager. Ward admitted later that he had “trembled about that d——d telegram of Monkhood [an alias used by Ward] & Harry Smythe which would, if interpreted, have brought [railroad man James] Craig’s business in…which I have steered clear of.” What had Butler overlooked while savoring Ward’s cigars? Was there another ring of corruption around the impeachment, one connecting Collector Smythe with the Missouri railroad man and the King of the Lobby? Because Butler never found out, neither have we.