Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (26 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Although William Evarts held no government position, the president’s lawyer (and Seward confidant) played a central role in the Schofield nomination. On the afternoon of April 21, a recess day after the defense closed its evidence, Evarts invited the general to his rooms at Willard’s Hotel. The lawyer explained that the president was prepared to appoint him as secretary of war. A note from General Grant interrupted them. The general-in-chief had business with Schofield, who was staying at the Grants’ home while in Washington City. Schofield excused himself, but not before gaining Evarts’s agreement that he could talk to Grant about the offered appointment as war secretary.

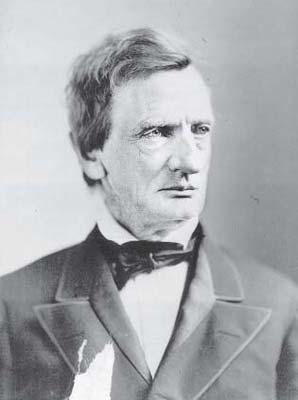

William Evarts, New York lawyer, who led the president’s defense inside and outside of the Senate.

Schofield kept a level head. He needed to be sure that his elevation would not rile the general-in-chief. He would fail as war secretary if he were caught in a cross fire between the president and Grant. After dinner that evening, the two generals went for a walk. Schofield described the proposition from Evarts. Grant, who viewed Schofield as a friend, had no objection to the appointment. With that assurance, Schofield returned to Evarts’s hotel room at 8

P.M.

Evarts explained that although there was no factual basis for impeachment, some Republicans would not vote for acquittal unless the War Department was restored to normal. Schofield had been selected, Evarts said, because Grant would accept him (which Schofield knew was true), which would satisfy Republicans. The appointment was not a personal matter for the president, the lawyer went on, because “he really had no friends.”

When Schofield returned to the Grants’ home at 11

P.M.

, Grant insisted he would never believe a pledge by Johnson of future good conduct, then added that the president should be removed from office. Yet Grant still thought it proper for Schofield to accept the appointment. Next morning, Schofield told Evarts that he could go forward if the president abandoned the “annoying irregularities” in War Department matters that had developed during months of struggle with Stanton. When Evarts objected that Johnson could make no such commitment, Schofield replied that he would assume that his condition was acceptable if the president went through with the nomination.

Evarts kept tight control over the announcement of Schofield’s nomination. The president sent Colonel Moore to deliver it to the Senate on Thursday, April 23, but Evarts waved the colonel away. The moment was not right. On the next day, the third day of closing arguments, Moore was back at the Senate with the nomination in hand. This time, Evarts nodded yes, and the paper was delivered. It created, Moore wrote in his diary, “considerable interest.” Judge Curtis gave Moore a cheering message to carry back to the president. “[D]uring the last twenty-four hours impeachment had gone rapidly astern.”

The press reported the Schofield nomination as an olive branch extended to doubtful Republican senators, and noted that Grant did not object to it. That last point was the most important one. Grant could have scuttled the maneuver by advising Schofield not to take the appointment. Partisans like Stanton and Stevens doubtless would have preferred for Grant to do so, denying the president any advantage in the trial. The general-in-chief did not, however, consult political advisers on the question. He decided on his own. Every day, he knew, the standoff over the War Department snarled the military. Even though the appointment might save Johnson, Grant would not obstruct resolution of that standoff. The Schofield nomination represented a surprising act of mutual forbearance between Johnson and Grant, whose dislike for each other had not abated. If Johnson would swallow his pride enough to appoint a secretary of war whom the Senate could confirm, Grant would not stand in his way.

A couple of days later, though, the general-in-chief changed his mind. On April 25, he dashed off a one-sentence note to Schofield suggesting that he decline the promotion to war secretary. Grant may have come to regret Schofield’s nomination as it began to seem like a lifeline for the president. In reply, Schofield pointed out that he had already agreed to accept the position.

Despite the conciliatory gesture, Andrew Johnson still hungered for revenge against Grant. On the day after the Schofield nomination was announced, the president mused over ways to get at Grant “when this trouble is over.” He had an idea. Because Grant’s commission as General of the Army did not award him command of the army, and because Johnson had never appointed him to that command, Johnson thought he might still “get hold of him after a while.”

As closing arguments filled the Senate Chamber, the head-counting gained in intensity. The president learned that Stanton was complaining that Fessenden, Grimes, and other Senate Republicans “had gone back on him.” The news must have given Johnson hope.

Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, who had sponsored fourteen Reconstruction statutes, was leaning toward acquittal. In late February, when Johnson tried to appoint Lorenzo Thomas as war secretary, Trumbull had been “earnest for impeachment.” During the trial, though, his doubts increased. Though he deplored Johnson’s opposition to Congress on Reconstruction, Trumbull was not inclined to convict the president on any of the eleven impeachment articles.

In the tumult that followed the final impeachment votes, Fessenden, Grimes, and Trumbull received grudging credit for having expressed their doubts early. Few challenged the integrity of those three early defectors. Others of the doubtfuls did not receive a similar benefit of the doubt.

For example, Senator Edmund Ross of Kansas, protégé of Indian trader Perry Fuller, inspired little respect. “A great and insidious influence is operating upon Ross,” wrote one observer, “who is a weak man and may be artfully operated on without his apprehension of the fact.” Joseph Fowler of Tennessee was still sitting with the Democrats, so his inclinations were a source of Republican anxiety. Uncertainty also surrounded Peter Van Winkle of West Virginia, who often voted without regard to party.

Though the final outcome could not be predicted, by the last week of April the president had made progress toward securing the Republican defections he needed. The work of corralling votes would continue behind the scenes. Onstage, the stars of the show, the lawyers, were eager to deliver closing orations so brilliant, so incisive, so inspirational, that they would change history. If they fell short of that goal, it would not be for lack of effort.

APRIL 22–MAY 6, 1868

[W]e have been wading knee deep in words, words, words…. [T]here are fierce impeachers here, who, if [faced with] the alternative of conviction of the President, coupled with their silence, and an unlimited opportunity to talk coupled with his certain acquittal…would instantly decide to speak.

R

EP.

J

AMES

A. G

ARFIELD,

A

PRIL

28, 1868

T

HE EXCITEMENT WAS

back. On Wednesday, April 22, crowds flocked to the Senate chamber to hear closing arguments. The president was still in the White House. Secretary Stanton was still camped out in the War Department. One of them would be moving very soon. Spring temperatures brought ladies and gentlemen to the Capitol in their finest outfits, eager to hear soaring rhetoric about the fate of the Republic. This day, however, fell short on that score.

The session began with a ninety-minute dustup over how many speeches could be delivered on each side. Finally acceding to the House managers, the Senate grudgingly allowed an unlimited number of speakers. Manager John Logan of Illinois submitted his remarks in written form. In view of their great length, the Senate had cause to be grateful. Manager James Wilson of Iowa was even more gracious, offering no statement at all. Despite these self-denying gestures, the final speeches would consume almost two weeks. Four lawyers would speak for each side, in an alternating pattern: a House manager would begin, then two defense lawyers, followed by two managers. The last two defense lawyers would speak, and then a final House manager would conclude the ordeal. Americans in the 1860s were accustomed to long addresses, often treating oratory as a spectator sport. Nevertheless, the number and length of the closing arguments would wear down both the senators and the public.

Manager George Boutwell of Massachusetts opened for the prosecution. Having worked doggedly for more than a year to remove Andrew Johnson from office, Boutwell had to take some satisfaction in the moment. His address consumed three hours, until the Senate called it quits for the day.

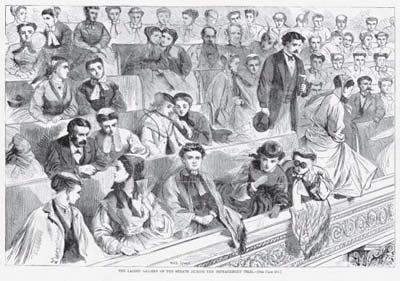

The compact Boutwell, then fifty years old, did not electrify audiences. His solemn delivery could grow wearisome. Senators became distracted after the first thirty minutes. The galleries began to rustle. The ladies turned their opera glasses on one another, with even the occasional “telescopic flirtation.”

The Ladies’ Gallery in the Senate during the trial.

Whatever his rhetorical limitations, Boutwell presented a thoughtful analysis. The president, he argued, had no innocent intent in the War Office episode. Johnson knowingly violated the Tenure of Office Act without taking any step to test the statute in court. Reviewing the legislative history of the statute, Boutwell challenged the defense view that it did not apply to Stanton. He made deft use of learned allusions, deploying a passage from

Hamlet

to compare Johnson’s Cabinet to the simpering servility of Polonius. He also offered the most obscure classical analogy of the trial, equating the president’s performance in office with the disastrous administration of Sicily by Caius Verres in 80

B.C.

Boutwell’s bland demeanor cloaked a white-hot rage against Andrew Johnson. The anger burned through on the second day of his peroration. He denounced Johnson for delivering to Southerners the power “they had sought by rebellion,” condemning the region to “disorder, rapine, and bloodshed.” Then he offered an astronomical interlude, describing a part of the night sky where no heavenly body could be seen. That “dreary, cold, dark region of space,” Boutwell continued, was the only proper destination for the president:

If this earth was capable of the sentiments and emotions of justice and virtue,…it would heave and throw,…and project this enemy of two races of men into that vast region, there forever to exist in a solitude as eternal as life….

Most press accounts ignored this powerful image of a convulsing planet ejecting the horror that was Andrew Johnson, but defense lawyer William Evarts was paying close attention. He would make the managers regret Boutwell’s astronomical curse.

The press neglected Boutwell’s moment of excess because the next speaker, defense lawyer Thomas Nelson of Tennessee, offered nothing but excess. A Whig from East Tennessee, Nelson had opposed Johnson politically for many years. The two reconciled in the dangerous days of 1861, when both opposed secession from the Union.

The outline of Nelson’s speech made sense. By showing the president’s human side, the Tennessean aimed to tear down the monstrous image created by the Radicals’ perfervid rhetoric. Nelson’s manner, though, was ill suited to the task. After his opening, shouted question, “Who is Andrew Johnson?” Nelson rapidly lost his listeners’ attention. He was loud and confrontational, denying that the Senate could legitimately conduct the trial without Southern senators present. One observer thought Nelson “mistook the Senate for a set of Tennessee sinners, and appealed to its feeling instead of its judgment.” Another described his oration as “a great impassioned appeal to defend the President without strict regard to time and place, the rules of logic, or the nicer distinctions in grammar and philology.” When Nelson ended his seven-hour speech on Friday afternoon, April 24, most seats were empty. Of the managers, only Butler remained. Judge Curtis drowsed alone at the defense table.

Nelson also inserted a distraction: the Caribbean guano island of Alta Vela. Boutwell had referred to the withdrawal of Jeremiah Black as one of Johnson’s defense lawyers. Black abandoned the president when Johnson refused to intervene in favor of his clients’ claim to bird waste on Alta Vela. In answer to Boutwell, Nelson revealed a letter to the president, dated six weeks earlier, in support of Black’s clients. Drafted by Ben Butler, the letter was signed by three other managers (Bingham, Stevens, and Logan), and several more Republicans. These impeachers thus petitioned the president on behalf of guano claimants as they attempted to remove him from office. In truth, the letter had nothing to do with impeachment, but those who signed it suffered deep embarrassment.

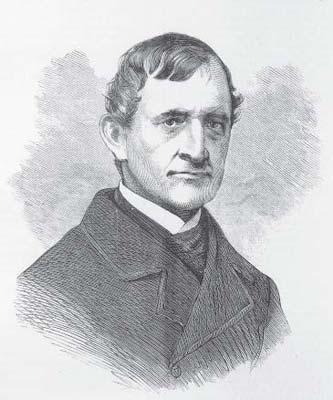

The next defense lawyer, William Groesbeck of Cincinnati, elicited a far different response. Groesbeck had been to Washington City before. He had served a single term as a Democratic congressman and attended the “Peace Convention” that met in Washington in early 1861 to try to head off war. Still, he appeared before the Senate as a tall, lanky unknown. He had not spoken during the trial. The beaky lawyer not only finished his address in a single day but also bewitched his audience. One listener claimed that Groesbeck gave the finest speech ever heard in the Senate.

In contrast to Nelson, Groesbeck was not combative. In contrast to Judge Curtis, he was not dry. Groesbeck impressed his listeners with a careful description of the historical precedents for presidential removal of subordinates. Instead of denouncing the impeachers, he expressed dismay that Johnson could be ousted based on “these miserable little questions.” He drew a sympathetic portrait of his client. Johnson, Groesbeck insisted, “trod the path on which were the footprints of Lincoln,” seeking only reconciliation.

William S. Groesbeck of Cincinnati, counsel for President Johnson.

Ah, he was too eager, too forgiving, too kind. The hand of conciliation was reached out to him and he took it. It may be that he should have put it away, but was it a crime to take it? Kindness, forgiveness, a crime?

Groesbeck thus reinvented the congenitally angry president who had demanded that traitors be hanged, who had accused the Radicals of seeking his assassination, whose dedication to states’ rights prevented him from compromising with Congress, and who had abandoned Southern Unionists and freedmen to brutal violence. In Groesbeck’s version of the world, Andrew Johnson’s only crime was excessive kindness.

After a Sunday of what must have seemed like golden silence, the week began with the much anticipated address by Thad Stevens for the prosecution. Throughout the spring, the press had been transfixed by the Pennsylvanian’s decline, meticulously charting his progress to the grave. His daily attendance at the trial was compelling stuff. “He seems to breathe with difficulty,” reported the

Cincinnati Commercial

. “His voice has that dreadful low, grating sound that we hear from deathbeds.” On the Senate floor, Stevens sipped brandy and port while eating raw eggs and terrapin. He limped unsteadily on his club foot or rode in a chair hoisted by powerful porters. His gaunt face and empty gaze seemed to summon judgment from the world beyond.

For twenty-five minutes on Monday, April 27, Stevens gave it a try. He read from foolscap sheets, his voice steadily weakening until almost no one could hear him. Stevens accepted Ben Butler’s offer to read the final half of the address for him.

Acknowledging that the Senate trial was no place for “railing accusation,” Stevens could not help himself. He demanded that Johnson “be tortured on the gibbet of everlasting obloquy.” He insisted that impeachment was the correct remedy for the president’s political offenses. Stevens tried to widen the Senate’s focus, to show that the case against Johnson could turn the nation toward a society based on equality. Brushing past the Tenure of Office Act, Stevens deplored Johnson’s creation of Southern state governments in 1865 and his opposition to Congress’s Reconstruction laws. If the president was unwilling to enforce the laws, Stevens said, he should “resign the office…and retire to his village obscurity.”

Following the sepulchral Stevens, Manager Thomas Williams delivered a speech that emptied the chamber until the next day. When he was done, the galleries filled in anticipation of the address of defense lawyer William Evarts. The arrivals included Anthony Trollope, the novelist, who sat with the British ambassador. The ruddy, gray-bearded writer used an ear trumpet to follow the proceedings while accepting cards from ladies in the gallery who were eager to praise his books. During a recess, Trollope’s contempt for the impeachers led him into a spirited argument with a young Republican who found the novelist rude and violent.

Before Evarts could speak, Ben Butler was on his feet. Guano was on his mind. He attacked defense lawyer Nelson for his “insinuated calumny” in revealing Butler’s letter supporting the Alta Vela claimants. The Massachusetts manager stressed that his involvement with the guano claims predated the impeachment and was unrelated to it. Nelson scornfully answered with an implied challenge to a duel. After their squall erupted again the next day, it receded to its proper insignificance, leaving behind one of the better jokes of the spring: Nelson and Butler supposedly fought their duel, the story went; after Nelson was shot through the brains and Butler through the heart, both of them walked back to the Capitol, uninjured.

Unruffled by Butler’s outburst, Evarts began an immense oration. A slim figure of less than medium height, the lawyer spoke with few notes, one hand in his coat pocket while the other gestured with clutched eyeglasses. Putting in an hour on Tuesday, Evarts carried on for most of the Wednesday session, all of Thursday’s, and much of Friday’s. In all, his argument consumed more than ten hours. Even in 1868, ten hours was a long time to listen to one man. Evarts hoped to make his speech immortal, John Bingham jeered, by making it eternal. (Bingham would soon have to eat those words.)

Despite his prolixity, Evarts held his audience in the palm of his hand. As one observer noted of the address, “although it seems interminable, it is not tiresome.” Evarts presented clear, earnest reasoning with an easy grace and a pleasing voice. The substance of his remarks varied little from those offered by Judge Curtis and Groesbeck. The difference was that Evarts understood the power of humor, and the power of ridicule.

On his second day, Evarts scored heavily with his lighthearted review of Manager Boutwell’s wish for Johnson to face “astronomical punishment” in the coldest, darkest place of the heavens. The defense lawyer noted that Boutwell thought the Constitution allowed the removal of Johnson but “has put not limits on the distance.” In an extended fancy, Evarts imagined Boutwell bearing the president on his shoulders to the top of the Capitol dome and flinging the apostate “upon his flight, while the two houses of Congress and all the people of the United States shall shout, ‘

sic itur ad astra

[thus do we reach the stars].’” Joined by Boutwell himself, the listeners roared with laughter as the chief justice strained to gavel them to a more decorous state.