Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (18 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Boutwell betrayed no embarrassment over these unfortunate impeachment articles, which one Senate aide thought “savor of the attorney too much.” Modestly, Boutwell invited the House to revise or replace the articles as it saw fit: “We have no special attachment,” he said, “to the particular words and phrases employed.” They had little enough reason for such attachment.

The House debate was scheduled for all day Saturday and the following Monday. Seeing the impeachment articles for the first time that afternoon, several congressmen urged the House to slow down. Radical Republicans bemoaned the narrowness of the articles, which addressed only two episodes of Johnson’s many misdeeds. They ached to charge the president with his

real

crimes, all of them. A Democrat denounced the charges as trifling, while another observed that “ten articles have been presented, or rather ten specifications of one article.”

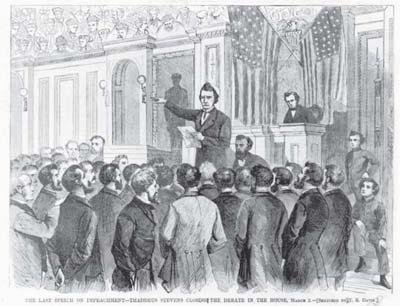

Another theatrical moment arose when Stevens closed debate on Monday, March 2. His words were bitter. Increasingly gaunt and pale, he began to read his speech from a seat facing the House. “Never,” he began, his voice weak, “was a great malefactor so gently treated as Andrew Johnson.” The House began to fall silent. Congressmen again strained to hear the words. This time strength came to the Pennsylvanian. He kept speaking. He complained that the committee, “determined to deal gently with the President,” had omitted many crimes from the impeachment articles. The articles covered, he lamented, only “the most trifling crimes and misdemeanors.”

Years began to fall away as the old man justified each article in turn. Stevens stood up. He began to gesture and his voice reached the gallery. Though trifling, he said, the articles should be approved so the nation could finally be rid of this pestilence in the White House. “Unfortunate man!” Stevens said to the rapt chamber, “thus surrounded, hampered, tangled in the meshes of his own wickedness—unfortunate, unhappy man, behold your doom.”

Boutwell brought forward revised impeachment articles, which now numbered only nine, one of the conspiracy articles having been blessedly dropped. The House rejected motions to add articles. Ben Butler of Massachusetts presented a lengthy new charge. After reciting several of the president’s stump speeches denouncing Congress, Butler’s article accused him of the high misdemeanor of bringing the presidency “into contempt, ridicule, and disgrace.” Here was a political offense pure and simple. Butler argued that his article tracked one presented against Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase more than sixty years earlier (one that was rejected by the Senate). Butler’s proposal was defeated—for the time being. The House then approved by overwhelming margins each of the nine articles proposed by the committee.

Stevens, closing debate on impeachment, March 2, 1868.

The House turned to designating those members who would act as prosecutors during the Senate trial, preparing the case and presenting the evidence. They would be the public face of the impeachment effort, standing in the Senate chamber and demanding the conviction of Andrew Johnson. The Republican caucus had designated seven “managers,” beginning with Boutwell (a leading Radical) and Bingham and Wilson (leading moderates). In a poignant turn, the caucus on its first ballot passed over Stevens. Many doubted he was strong enough to be an effective prosecutor. On a second ballot, those doubts yielded to respect for his relentless opposition to Johnson.

Three more Radicals were less obvious choices as managers. Dashing John Logan of Illinois commanded the Grand Army of the Republic, but was no great shakes as a lawyer. Thomas Williams of Pennsylvania was a respected lawyer, but was extreme in his hatred for the president. He had written the ineffective majority report for the impeachment resolution rejected by the House only ten weeks before.

And then there was Ben Butler of Massachusetts. Though he had served in Congress for less than a year, Butler would become the lead prosecutor. The

New York Times

explained that Butler was chosen as a House manager because of “his great ability and fertility of resource as a criminal lawyer.” The

Chicago Tribune

offered the jest that Butler “was one of the greatest criminal lawyers in the country, and Johnson the greatest criminal.” Few men in public life have overcome such memorably odd physical attributes. Touching lightly on Butler’s bald pate, drooping eyelid, and severe case of strabismus (cross-eyes), a Civil War officer left this description:

With his head set immediately on a stout shapeless body, his very squinting eyes, and a set of legs and arms that look as if made for somebody else, and hastily glued to him by mistake, [Butler] presents a combination of Victor Emanuel [King of Savoy], Aesop, [and] Richard III, which is very confusing to the mind.

One more crafty lawyer in a Congress that teemed with them, Butler had energy and intelligence that propelled him through a tumultuous public career. A lifelong Democrat, in 1860 Butler supported Jefferson Davis of Mississippi for president. He nimbly switched to the Union side when Southern guns fired on Fort Sumter. Securing a military command for which he had no qualifications, Butler became a Northern hero by welcoming escaped slaves into his camp. His army service mixed political triumphs with military failures. The popularity of “Old Cockeye” grew in the North when Southerners named him “Beast” for his heavy-handed occupation of New Orleans, then spiked again when he was christened “Spoons” for pilfering the silver from the Louisiana mansion where he made his headquarters. One war-derived nickname—“Bottled-Up Butler”—was less welcome, reflecting a military campaign during which his “bottled up” army was useless. According to the Massachusetts general, he declined Lincoln’s offer of second spot on the 1864 Republican ticket, the place that went to Andrew Johnson. Many, however, doubt the tale.

By the time Butler crashed into the House of Representatives in March of 1867, the former Democrat had become a full-fledged Radical Republican. One Republican was not surprised by the transformation, noting that “it never was General Butler’s habit to be moderate.” Thought by many to be the political heir to Stevens, Butler was already driving his finger into the eye of moderate John Bingham within three weeks of arriving in Congress. Observing Bingham standing on the Democratic side of the House, Butler declared the Ohioan had “got over to the other side not only in body, but in spirit.” Bingham, thin-skinned in the best of times, answered by denouncing Butler as a man “who recorded his vote more than fifty times for Jefferson Davis, the arch-traitor of this rebellion, as his candidate for President of the United States.” Then they took the gloves off.

Referring to one of Butler’s military failures, Bingham rejected with “scorn and contempt” the remarks of “the hero of Fort Fisher not taken, or Fort Fisher taken.” Butler replied that during the war “the only victim of [Bingham’s] prowess that I know of was an innocent woman hung upon the scaffold, one Mrs. Surratt” (one of the Booth conspirators). Drawing on the rich store of Butler nicknames, Bingham rejoined that the general’s accusations were “fit to come from one who lives in a bottle and is fed with a spoon.”

Remembering that and other encounters with Butler, John Bingham pitched a fit when the House Speaker announced the seven managers on March 2. Bingham was incensed to find his name in third position on the list, after Stevens and Butler. By reading the names in that order, the Speaker seemed to imply that Stevens would be chairman with Butler as his second. “I’ll be damned if I serve under Butler,” Bingham exploded. “It is no use to argue, gentlemen. I won’t do it.”

The House sidestepped Bingham’s flare-up by electing the managers without designating a chairman. The Ohioan was gratified to command the highest total vote, but was affronted anew when the managers themselves chose George Boutwell as their chairman. Intolerable! Bingham promptly announced his resignation as manager. To make peace, Boutwell declined the chairmanship in favor of the touchy prima donna from Ohio. Because Bingham led the moderate and conservative Republicans, the managers could not afford to lose him from the prosecution team.

The managers quickly approved two more impeachment articles, starting with Butler’s “stump-speech” article. The full House was restrained in its enthusiasm for that one, with eleven Republicans actually voting against it. No such diffidence applied to the final article. Adopted by a wide margin after no debate, Article XI would play a large role in the trial to come.

Proposed by Stevens and Wilson of Iowa, this last article was a clever mélange of complaints about the president: that he declared in 1866 that Congress represented only some of the states and had no power to propose amendments to the Constitution; that he had removed Stanton as war secretary in violation of the Tenure of Office Act; that he evaded the statute that required him to deliver military orders through General Grant; and that he thwarted the first Reconstruction Act. Article XI thus mixed a criminal offense (the Stanton question) with political ones. By lumping several theories together, it aimed to sweep up the votes of senators who accepted one or another of those theories, combining them all (the drafters hoped) into a two-thirds majority for conviction.

There was no precedent for such a “catch-all” impeachment article, which sharply tilts the odds against the impeached official. The accused cannot challenge allegations one at a time, but must confront several at once. In its one-sidedness, Article XI bears the handprint of Stevens’s unabashed drive to remove Johnson from office. Regrettably, it became a model for future impeachments, which similarly lumped a range of charges into single impeachment articles. The technique is designed to make it easier to vote for conviction. If satisfied that at least one of many allegations has been proved, a senator is justified in voting to convict. Even if there is no two-thirds majority on any single allegation, a catch-all impeachment article may bring conviction as some senators are persuaded by allegation “A,” others by allegation “B,” and so on.

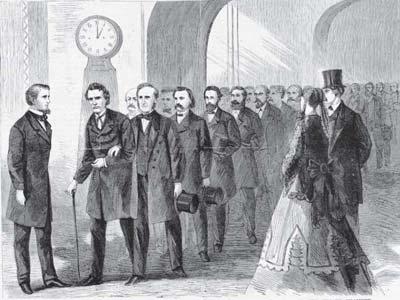

To deliver the impeachment articles on Wednesday, March 4, the entire body of House Republicans marched in a sober column from their chamber, through the Capitol rotunda, and into the Senate. Leading the column, the seven managers gave no hint of their rocky relations with each other. Inside the Senate, Bingham and Boutwell led the procession, arm in arm, followed by Butler and Wilson, then Logan and Williams. Stevens came last, slowly passing down the Senate’s center aisle, no longer carried in his chair but with a friend supporting him on either side. Because of his still fierce visage, because his grip on life seemed so slight, because he remained the soul of the impeachment, the Pennsylvanian took central place in the tableau even without a speaking part.

Members of the House of Representatives march through

Bingham rose after the managers sat in cushioned armchairs at the front of the chamber. The other congressmen stood in a semicircle behind the senators’ desks. Bingham read through the eleven impeachment articles, a tedious journey through dense legal undergrowth that nevertheless commanded the chamber’s full attention. Those present had to marvel at the speed with which the House had acted. Less than two weeks had passed since Lorenzo Thomas tried to claim Stanton’s office.

As it moved from one side of the Capitol to the other, the impeachment story was changing in important ways, starting at the White House. The reality of impeachment sobered the president. He had thrown caution to the winds when he placed his political hopes on the slight shoulders of Lorenzo Thomas. The impeachment stampede had a salutary effect on Johnson’s decision-making. For the next ninety days, he seemed to remember the skills that had served him through a long political career. He stopped issuing enraged and enraging proclamations, or flinging antagonistic barbs in extemporaneous statements. In the words of one congressman, he became “guarded against the folly of talking, which was his easily besetting sin.” A committee from Baltimore presented him with a resolution of support in late February. Johnson’s short remarks were dignified and determined. With his office on the line and the prospect of permanent disgrace yawning before him, Johnson also would discover compromise, an act he had mostly foresworn since becoming president.