Imagined Empires (8 page)

Authors: Zeinab Abul-Magd

In 1780, only one year after Savary's visit, King Louis XVI officially dispatched C.S. Sonnini, an engineer in the French Navy and a prominent scientist, on a mission to Egypt. Sonnini's observations were published in the voluminous

Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt Undertaken by Order of the Old Government of France.

During his journey, Sonnini encountered difficult situations, in which he faced Mamluk dictators as well as “superstitious and ungoverned barbarians”âboth Arabs and Coptsâbut he managed to compile his recommendations on creating a future French colony in Egypt.

12

With an unmistakable tone of superiority, Sonnini proposed various possibilities for colonial exploitation of Egypt's underdeveloped commercial and agricultural resources. Sonnini depicted in detail the colossal Pharaonic monuments of Upper Egypt and said that in this region, and under French governance, Egypt could recover its lost glory. More importantly, he forged

images of the Arab tribes and Copts of Upper Egypt as potential allies of the French would-be liberators. These two groups, however, viewed things quite differently.

In Qina Province, Sonnini's vision of developing trade at the port of Qusayr was almost identical to Savary's. Sonnini maintained that Qusayr and Qina could be turned into international centers for Indian and Asian commerce, and he also proposed reviving the ancient canal between Qusayr and Qina. He similarly and romantically asserted that the possession of this commercial area would render France in de facto control of Indian Ocean and Arabian Gulf trade, which would certainly be a great victory against Britain, France's rival. Interestingly, he indicated that Qusayr was particularly important for the Parisian coffee drinkers who cared about getting pure mochaâimported from the Yemeni port of Mocha via the Upper Egyptian port city: In Qusayr and Qina one could find the best Yemeni coffee, a product that was typically adulterated several times with American colonial coffee before reaching Paris. Sonnini explains:

[Qusayr] is the track the caravans pursue, which transport into Arabia the commodities of the Egypt, and which carry thither the coffee of Yemen. The greater number of these caravans deliver to

Kous

[Qus]. Some also go to

Kenné

[Qina], and others to

Banoub.

If you wish to be supplied with excellent coffee, you must go to one of these three places to find it. When once it arrived to Cairo, or had crossed the Nile, it was no longer pure. Merchants were waiting there to mix it with the common coffee of America. At Alexandria it underwent a second mixture by the factors who forwarded it to Marseilles, where they did not fail again to adulterate it: so that the presented Mokka [Mocha] coffee, which is used in France, is often the growth of the American colonies, with about a third, and seldom with a half, of the genuine coffee of Yemen. . . . When I was in

Kous

an hundred weight of this coffee, unadulterated, and of the first quality, cost . . . one hundred and five franks. . . . How is possible to believe that they should have real Mokka coffee at Paris at the rate of five shillings a pound?

13

Moreover, Sonnini elaborated on the immense fertility of land in Upper Egypt. The land of all Egypt was rich, but “this uncommon fertility is still more brilliant to the south than to the north.” The south might be hot and dry, but its soil was “infinitely more fruitful than the moist soil of the Delta.”

14

Then he added similar observations to those of Savary about the backwardness of cultivation in the region, because the natives were “ignorant and lazy” and the Mamluks were careless, and the need for the enlightened

French to reform it. The hot weather in Upper Egypt might deter the French from inhabiting the future “colony,” but Sonnini affirmed that it was still a proper environment to live in.

15

Liberating the Egyptians and achieving these great economic goals would entail the collaboration of internal allies, and Sonnini envisioned the Arab tribes and Copts of Upper Egypt as qualified candidates. Proud of their honorable lineages, the Arab tribal leaders were constantly rebelling against the Caucasian Mamluks, while they were hospitable and generous with Sonnini. The Copts, although not Catholics, were fellow Christians. Nonetheless, two encounters that Sonnini had with an Arab leader and a Coptic merchant reveal that there was a serious misunderstanding on the part of the French expert. Sonnini the physician assumed cultural superiority with the Arab leader, when the latter clearly perceived him as another servant. Sonnini trusted the Coptic merchant, when the latter obviously thought him a naïve, foolish foreigner who would be taken advantage of. Suffering the illusions of supremacy, Sonnini created fatal misrepresentations that the troops of his country would pay for later.

While in Qina Province, Sonnini was hosted by Shaykh Ismaâil Abu âAli, the Arab governor of a district. Upon his arrival by boat in Luxor, Sonnini heard that the Arab prince was there inspecting his tax farms, so he quickly crossed the river to meet the man of great power. Sonnini described the prince as an ugly, dirty old man, “disgusting,” but he had a clear and intelligent mind. Sonnini witnessed him running administrative matters in a governing council with noticeable justice: “A concourse of Arabians and of the inhabitants encircled him; he listened to them with attention whilst he was dictating to his secretaries; he issued his orders and gave his dictions with surprising distinctness and regard to justice.”

16

When the shaykh finished this case, he looked with disinterest at the Frenchmanâwho was patiently waiting at the door of the tentâand asked with a “voice sufficiently dry” who he was. Sonnini came close and gave him a letter from Murad Bey, the Mamluk ruler in Cairo, recommending him for the job of private physician. The ill shaykh hired him, gave him some instructions, and resumed his affairs. Sonnini sat under some trees outside the tent, unaware that he was now considered another one of the shaykh's servants. The next morning, the shaykh woke up and did not find Sonnini by him, so he shouted, Where is the doctor? Where is the doctor?

(Fen hakim? Fen hakim?)

. Sonnini was in Luxor then, so the shaykh sent him a message ordering him to come back and stay at the prince's disposal: “He dispatched a messenger after me to say, that

Mourat Bey having sent me to his assistance, I must not think of quitting him, and that from that period I was

his physician.

This message was concluded with an order to hold myself in readiness the next day, to accompany Ismain in his journey.”

17

Another Arab tribal chief, the shaykh of Luxor, gave Sonnini orders “with much polite condescension,” as Sonnini put it. Sonnini knew that his importance among Arab shaykhs was derived from his medical skills rather than his white race or civilized manners, so he sometimes lied in order to maintain his position. He pretended to know the cure of illnesses when he did not. The mayor shaykh of Gurna, for instance, “was afflicted with a disorder which could not be cured except by a difficult operation. I [Sonnini] took care not to tell him that this cure was beyond my skill; I gave him some medicine which could do him neither good nor bad.”

18

While conducting himself in this unprofessional manner, Sonnini stated that “it is impossible to depict the customs of a degraded people, of whom barbarism has taken entire possession, without interference of ideas so dishonorable to humanity, ideas of crimes and robberies, which blend in the picture, and constitute the greatest part of it.”

19

At any rate, Sonnini's general impression of the Arab shaykhs throughout his journey in Qina Province implied that those dark leaders were generous, powerful, and just and that Frenchmen could be good allies. He suggested that inciting the Arabs to revolt against the Mamluks could be a fruitful strategy, proposing that “the various tribes . . . perhaps ought to be disposed for revolution rather than attacked as enemies.”

20

Sonnini similarly viewed Copts as barbarians whom the French had no choice but to count on as fellow Christians. The Copts of Upper Egypt, in fact, harbored bitter sentiments against European Christians, because Catholic missionaries were spreading throughout the region and denouncing the native Orthodox faith. European monks were not successful in converting Copts to Catholicism, but they surely disturbed their lives and earned their hatred. Sonnini explained,

The name of

Frank,

which in the East denotes all Europeans of whatever country, held in esteem among Turks, despised in the cities of Lower Egypt, was considered with horror by the inhabitants of the Said [Upper Egypt]. This hatred is instilled by the Cophts, who are more numerous here than in those districts farther to the north. They felt sore at the arrival of some missionaries, who came from Italy purposely to preach against them, to expose them openly as heretics and dogs, and do damn them without pity . . . . These pious injuries had perhaps merit in the view of theology; but they were extremely prejudicial to commerce and the increase of knowledge.

21

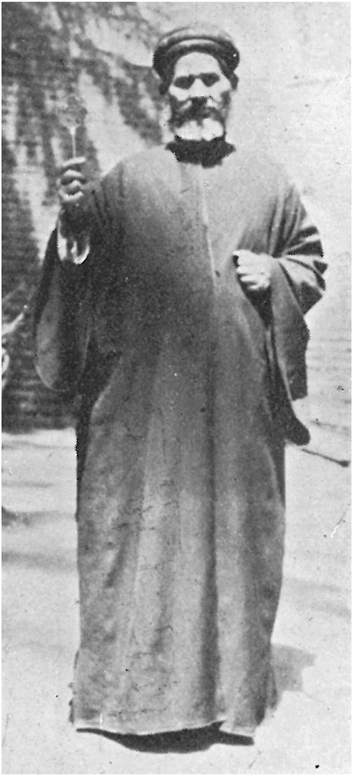

FIGURE 4.

An Upper Egyptian Coptic priest.

In the city of Qus, just north of Luxor, Sonnini met a wealthy Copt by the name of Muâallim Boqtor, a highly respected merchant. Although a Catholic convert himself, Boqtor did not hesitate to take advantage of Sonnini, who wanted to embark on a journey to the port of Qusayr. It was a harsh trip of three days in the eastern desert and required special arrangements, so Boqtor offered to take Sonnini there safely. Boqtor kept taking money and gifts from Sonnini under the guise of preparing for the trip. Time passed and the journey

did not take place. In fact, the Copt colluded with a Turkish merchant to rob as much money and other luxuries as possible from the conceited Frenchman, and the pair eventually informed him that the trip was delayed for security considerationsâfor fear of Bedouin attacks. Then they asked him to leave his luggage with the Turk if he still wanted to go. Foreseeing their intention of robbing his belongings, Sonnini refused, cancelled the trip, and demanded his payments back. They first refused to refund him, but they did when he threatened to complain to his master, Shaykh Ismaâil.

Sonnini concluded that the Coptic merchant was just another of Egypt's many thieves and added that the Mamluks were better than the dark native Egyptians: “Muâallim Boqtor, who had so often promised to see me conducted to

Cosseir

. . . was like all his fellow citizens, nothing else but a traitor . . . . I here feel it incumbent on me to say, that for the most part I have had better reason to applaud the conduct of the Mamelucs than the natives of Egypt . . . . [Mamluks] possessed a certain pride and blunt harshness . . . whilst the Cophts, dark and designing, insinuating and deceitful, distinguished himself by the cringing and submissive deportment of the most abject slave.”

22

Nevertheless, Sonnini still insisted that the Copts needed Europeans as enlightened liberators. He condemned the way Copts were treated in Egypt, “a country where the name of Christian merely is a crime.” Copts enjoyed prestigious government positions and wealth, but the Mamluks arbitrarily confiscated their properties. Copts needed to understand the difference between missionaries and other Europeans who went to Egypt to assist rather than insult them, said Sonnini.

23

During the mid-1790s, the images that Sonnini and similar experts constructed fed into the ideological underpinnings on which Paris based its decision to colonize Egypt. Political cleavages in the French Republic broke out in debates about the importance of France's imperial expansion overseas, especially after losing many colonies in the Americas. Historian Juan Cole indicates that there were two competing ideological trends with regard to colonialism: liberalism and conservatism. Discussions between them were heated in the legislature and the Directoryâa council of five men elected from the legislature. The original revolutionaries, the Jacobins, were against colonialism and called both for ending it and slavery. Another group of politicians argued that it was imperative for France to obtain external colonies in order to “prosper.” Colonizing Egypt for its trade and sugarcane cultivation and, above all, to weaken the British Empire in India, were all key rationales that many French imperialists contemplated. The conservative camp eventually

triumphed, and the concept of “satellite republics” was born. Colonies were to be turned into republics modeled after France, liberated from old oppressive regimes and enjoying democracy and freedom of the press, but controlled by Paris. The French would seek to create such satellite republics worldwide, starting with weaker areas in Europe, such as Italy.

24

In 1798, echoing Savary and Sonnini, one legislator by the name of Joseph Eschasseriaux argued that Egypt was “half-civilized” and easy to conquer. Cole quotes Eschasseriaux as saying, “What finer enterprise for a nation which has already given liberty to Europe [and] freed America than to regenerate in every sense a country which was the first home to civilization . . . and to carry back to their ancient cradle industry, science, and the arts, to cast into the centuries the foundations of a new Thebes or of another Memphis.”

25