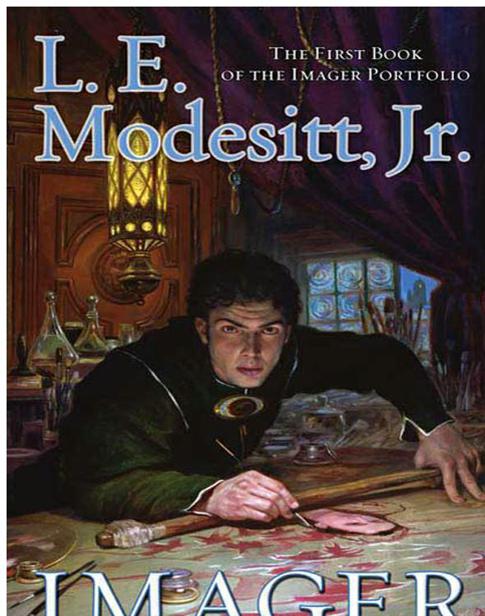

Imager

Authors: Jr. L. E. Modesitt

Imager

Tor Books by L. E. Modesitt, Jr.

The Imager Portfolio

Imager

Imager’s Challenge

(forthcoming)

The Corean Chronicles

Legacies

Darknesses

Scepters

Alector’s Choice

Cadmian’s Choice

Soarer’s Choice

The Lord Protector’s Daughter

The Saga of Recluce

The Magic of Recluce

The Towers of the Sunset

The Magic Engineer

The Order War

The Death of Chaos

Scion of Cyador

Fall of Angels

The Chaos Balance

The White Order

Colors of Chaos

Magi’i of Cyador

Wellspring of Chaos

Ordermaster

Natural Ordermage

Mage-Guard of Hamor

The Spellsong Cycle

The Soprano Sorceress

The Spellsong War

Darksong Rising

The Shadow Sorceress

Shadowsinger

The Ecolitan Matter

Empire & Ecolitan

(comprising

The Ecolitan Operation

and

The Ecologie Secession

)

Ecolitan Prime

(comprising

The Ecologic Envoy

and

The Ecolitan Enigma

)

The Forever Hero

(comprising

Dawn for a Distant Earth, The Silent Warrior

, and

In Endless Twilight

)

Timegod’s World

(comprising

Timediver’s Dawn

and

The Timegod

)

The Ghost Books

Of Tangible Ghosts

The Ghost of the Revelator

Ghost of the White Nights

Ghost of Columbia

(comprising

Of Tangible Ghosts

and

The Ghost of the Revelator

)

The Hammer of Darkness

The Green Progression

The Parafaith War

Adiamante

Gravity Dreams

Octagonal Raven

Archform: Beauty

The Ethos Effect

Flash

The Eternity Artifact

The Elysium Commission

Viewpoints Critical

Haze

(forthcoming)

The First Book of the

Imager Portfolio

L. E. MODESITT, JR.

A TOM DOHERTY ASSOCIATES BOOK

NEW YORK

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and

events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s

imagination or are used fictitiously.

IMAGER: THE FIRST BOOK OF THE IMAGER

PORTFOLIO

Copyright © 2009 by L. E. Modesitt, Jr.

All rights reserved.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Tor

®

is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Modesitt, L. E.

Imager : the first book of the imager portfolio / L. E. Modesitt, Jr..—1st ed.

p. cm.—(Imager portfolio ; 1)

“A Tom Doherty Associates book.”

ISBN-13: 978-0-7653-2034-6

ISBN-10: 0-7653-2034-7

I. Title

PS3563.O264I43 2009

813'.54—dc22

2008046496

First Edition: March 2009

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Steve and Marge Bennion,

in recognition of quiet courage

Table of Contents

After working with David Hartwell and Tom Doherty for more than twenty-five years, during which time Tor has published all of my books, now totaling more than fifty, it’s long past time to acknowledge in print the debt I owe to them both for believing in what I write and in supporting it by publishing the books with care and consideration.

743 A.L.

Commerce weighs value, yet such weight is but an

image, and, as

such, is an illusion.

The bell announcing dinner rang twice, just twice, and no more, for it never did. Rousel leapt up from his table desk in the sitting room that adjoined our bedchambers, disarraying the stack of papers that represented a composition doubtless due in the morning. “I’m starved.”

“You’re not. You’re merely hungry,” I pointed out, carefully placing a paperweight over the work on my table desk. “ ‘Starved’ means great physical deprivation and lack of nourishment. We don’t suffer either.”

“I feel starved. Stop being such a pedant, Rhenn.” The heels of his shoes clattered on the back stairs leading down to the pantry off the dining chamber.

Two weeks ago, Rousel couldn’t even have pronounced “pedant,” but he’d heard Master Sesiphus use it, and now he applied it to me as often as he could. Younger brothers were worse than vermin, because one could squash vermin and then bathe, something one could not do with younger brothers. With some fortune, since Father would really have preferred that I follow him as a factor but had acknowledged that I had little interest, I’d be out of the house before Culthyn was old enough to leave the nursery and eat with us. As for Khethila, she was almost old enough, but she was quiet and thoughtful. She liked it when I read to her, even things like my history assignments about people like Rex Regis or Rex Defou. Rousel had never liked my reading to him, but then, he’d never much cared for anything I did.

By the time I reached the dining chamber, Father was walking through the archway from the parlor where he always had a single goblet of red wine—usually Dhuensa—before dinner. Mother was standing behind the chair at the other end of the oval table. I slipped behind my chair, on Father’s right. Rousel grinned at me, then cleared his face.

“Promptness! That’s what I like. A time and a place for everything, and everything in its time and place.” Father cleared his throat, then set his near-empty goblet on the table and placed his hands on the back of the armed chair that was his.

“For the grace and warmth from above, for the bounty of the earth below, for all the grace of the world and beyond, for your justice, and for your manifold and great mercies, we offer our thanks and gratitude, both now and evermore, in the spirit of that which cannot be named or imaged.”

“In peace and harmony,” we all chorused, although I had my doubts about the presence and viability of either, even in L’Excelsis, crown city and capital of Solidar.

Father settled into his chair at the end of the table with a contented sigh, and a glance at Mother. “Thank you, dear. Roast lamb, one of my favorites, and you had Riesela fix it just the way I prefer it.”

If Mother had told the cook to fix lamb any other way, we all would have been treated to a long lecture on the glories of crisped roast lamb and the inadequacies of other preparations.

After pouring a heavier red wine into his goblet and then into Mother’s, Father placed the carafe before me. I took about a third of a goblet, because that was what he’d declared as appropriate for me, and poured a quarter for Rousel.

When Father finished carving and serving, Mother passed the rice casserole and the pickled beets. I took as little as I could of the beets.

“How was your day, dear?” asked Mother.

“Oh . . . the same as any other, I suppose. The Phlanysh wool is softer than last year, and that means that Wurys will complain. Last year he said it was too stringy and tough, and that he’d have to interweave with the Norinygan . . . and the finished Extelan gray is too light . . . But then he’s half Pharsi, and they quibble about everything.”

Mother nodded. “They’re different. They work hard. You can’t complain about that, but they’re not our type.”

“No, they’re not, but he does pay in gold, and that means I have to listen.”

I managed to choke down the beets while Father offered another discourse on wool and the patterned weaving looms, and the shortcomings of those from a Pharsi background. I wasn’t about to mention that the prettiest and brightest girl at the grammaire was Remaya, and she was Pharsi.

Abruptly, he looked at me. “You don’t seem terribly interested in what feeds you, Rhennthyl.”

“Sir . . . I was listening closely. You were pointing out that, while the pattern blocks used by the new weaving machinery produced a tighter thread weave, the women loom tenders have gotten more careless and that means that spoilage is up, which increases costs—”

“Enough. I know you listen, but I have great doubts that you care, or even appreciate what brings in the golds for this household. At times, I wonder if you don’t listen to the secret whispers of the Namer.”

“Chenkyr . . .” cautioned Mother.

Father sighed as only he could sigh. “Enough of that. What did you learn of interest at grammaire today?”

It wasn’t so much what I’d learned as what I’d been thinking about. “Father . . . lead is heavier than copper or silver. It’s even heavier than gold, but it’s cheaper. I thought you said that we used copper, silver, and gold for coins because they were heavier and harder for evil imagers to counterfeit.”

“That’s what I mean, Rhennthyl.” He sighed even more loudly. “You ask a question like that, but when I ask you to help in the counting house, you can’t be bothered to work out the cost of an extra tariff of a copper . . . or work out the costs for guards on a summer consignment of bolts of Acoman prime wool to Nacliano. It isn’t as though you had no head for figures, but you do not care to be accurate if something doesn’t interest you. What metals the Council uses for coins matters little if one has no coins to count. No matter how much a man likes his work, there will be parts of it that are less pleasing—or even displeasing. You seem to think that everything should be pleasing or interesting. Life doesn’t oblige us in that fashion.”

“Don’t be that hard on the boy, Chenkyr.” Mother’s voice was patient. “Not everyone is meant to be a factor.”

“His willfulness makes an ob look flexible, Maelyna.”

“Even the obdurates have their place.”

I couldn’t help thinking I’d rather be an obdurate than a mal. Most people were malleables of one sort or another, changing their views or opinions whenever someone roared at them, like Father.

“Exactly!” exclaimed Father. “As servants to imagers and little else. I don’t want one of my sons a lackey because he won’t think about anything except what interests or pleases him. The world isn’t a kind place for inflexible stubbornness and unthinking questioning.”

“How can a question be unthinking?” I wanted to know. “You have to think even to ask one.”

My father’s sigh was more like a roar. Then he glared at me. “When you ask a question to which you would already know the answer if you stopped to think, or when you ask a question to which no one knows the answer. In both cases, you’re wasting your time and someone else’s.”

“But how do I know when no one knows the answer if I don’t ask the question?”

“Rhennthyl! There you go again. Do you want to eat cold rice in the kitchen?”

“No, sir.”

“Rousel,” said Father, pointedly avoiding looking in my direction, “how are you coming with your calculations and figures?”

“Master Sesiphus says that I have a good head for figures. My last two examinations have been perfect.”

Of course they had been. What was so hard about adding up columns of numbers that never changed? Or dividing them, or multiplying them? Rousel was more than a little careless about numbers and anything else when no one was looking or checking on him.

I cut several more thin morsels of the lamb. It was good, especially the edge of the meat where the fat and seasonings were all crisped together. The wine wasn’t bad, either, but it was hard to sit there and listen to Father draw out Rousel.