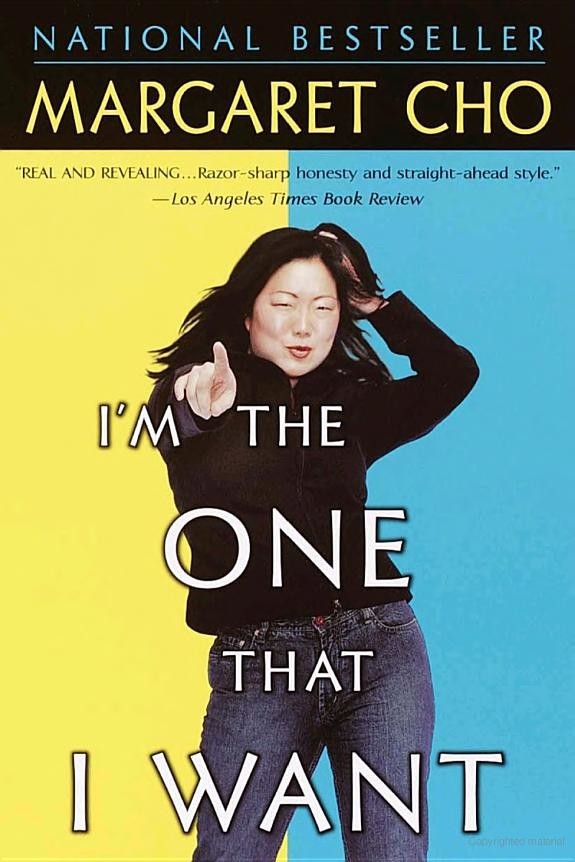

I'm the One That I Want

Read I'm the One That I Want Online

Authors: Margaret Cho

Tags: #Humor, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Topic, #Relationships

Table of Contents

“ACERBIC AND FRANK . . .

Her storytelling ability shines through in poignant yet lurid tales like that of a friend whose mother was an alcoholic, or her own horrible experiences of betrayal and rejection at summer camp.”

—

Creative Loafing

(Atlanta, GA)

“An anthem to self-reliance . . . Cho has met and mingled with a sweeping variety of characters in the course of her thirty-two years, from drag queens, punk rockers, and drug dealers to film producers, television stars, and Bill and Hillary Clinton.”

—

Vancouver Columbian

(WA)

“All the Korean family stories, dark days of adolescence, pill-addled comedy benders, and infuriating television show development meetings are in here, along with deeper insight into Cho’s anguished but very amusing mind. Careening between her reflections of a painful childhood and her ultimate acceptance of herself, warts and all, Cho celebrates the many gay men or, as she calls them, angels, that pulled her out of her own hell while still making catty remarks along the way.”

—

Instinct

(North Hollywood, CA)

“Fierce, funny, and wise . . . Though loosely based on her critically acclaimed stage show and smash box-office film of the same name, this book is a wholly original work, with an inspiring message for anyone who has ever been told they are not good enough, smart enough, pretty enough, or just not enough, period.”

—Asian Pages

This book is dedicated to my parents Young Hie and Seung Hoon Cho.

1

ALONE, STEALING AND WAVING

I was born on December 5, 1968, at Children’s Hospital in San Francisco.

My mother says, “You were so small. Just like this!” and she makes a fist and shakes it. “You grow so much! Can you imagine?! Just tiny baby!”

I can’t imagine being that small. It must have been the one time I didn’t worry about my weight. At 5 pounds, 6 ounces, I was the Calista Flockhart of the newborn set.

My earliest memories are mostly unpleasant. The first thing I can truly remember is standing in front of a sink in my footie pajamas being berated by a bunch of old people. They must have been my grandparents. I couldn’t wash my face, and they were making fun of me.

“Dirty face! Dirty face!” They all laughed and then started coughing.

My mother was about to leave me with them and, presumably, was hiding her guilt behind my inability to wash my face. I was so small I had to stand on a stool to reach the sink. I had a tremendous fear that if I immersed my face in the water I would not return, I would drown, or water would go up my nose, or I would somehow be hijacked.

I also feared that if I took my eyes off my mother, she would leave. And she did. My parents had a talent for leaving me places when I was very young. This had to do with immigration difficulties, living in San Francisco in 1968 and not being hippies, LBJ, men on the moon, and having their first child while being totally unprepared for reality. My father didn’t know how to break it to my mother that he was to be deported three days after I was born, so he conveniently avoided the subject. He didn’t lie; he simply withheld the truth and at the last minute, he left her holding the bag. Or me, as it were.

In my parents’ colorfully woven mythology, that was the one corner of the tapestry they carefully concealed. Knowing I probably wouldn’t remember, they kept it to themselves. But I did remember, perhaps not actual events but colors and shapes and feelings. The insides of planes, the smell of fuel, unfamiliar arms, crying and crying. Wanting my mom but not having the words, not even knowing what I wanted.

When questioned about it now, my mother spills forth resentment and regret. “Can you imagine mommy?! Oh! It was so terrible. I have to take care of you by myself and Daddy go back to Korea and then I have to send you to Korea and all this you only three days! Can you imagine?! Oh! I hate Daddy!”

My father says cryptically that he was testing the waters, scoping out the situation, whatever that means.

It was all an unfortunate turn of events, but in the spirit of my birthplace, I learned that if I couldn’t be with the one I loved, I would love the one I was with. I was one, and already somewhat of a slut.

I loved lots of stewardesses, and lots of old people. When I was reunited with my parents, my mother showed me pictures of an ancient, bony woman in a white Korean

ham-bok

. “She was your auntie and she take care of you when you baby. She love you soooo much! She just die. She is in heaven. But she take so good care of you. She love you soo much!!!!!” I believed she was dead because in the picture she looked like a skeleton, even though her wide smile made her kind and human. Some infantile, suckling part of me remembered her face and I wanted to weep with baby grief.

My mother’s father also died around this time in 1970. For some reason, her family did not let her know of his passing until long after the funeral. She sat on her bed holding one of those blue air-mail letters that is also its own envelope.

Par avion.

She was crying, letting her tears fall on the blue paper and smear the ink, odd Korean letters looking like a bunch of sticks that had fallen on the page. I was alarmed by her sadness—I hadn’t witnessed it before. I jumped on the bed and wrapped my small arms around her and said, “Don’t cry Mommy. I will be your mommy now.” I was fully aware of how cute I was being. I was destined for a career in show business.

Even then, I loved television, and my favorite thing to watch was the coverage of the Watergate scandal. I’d put my fist in my mouth and then smear my hand across the TV screen, watching the saliva make rainbow tracks all over Richard Nixon’s face.

We lived in a little apartment with my aunt and uncle on Washington Street. It was nice going from having no parents, to suddenly having four. My mother would make me special outfits—red wooly jackets with pillbox hats, just like Jackie O—and we’d all go to the park, where I would cry whenever I saw a dog.

My aunt and uncle ran a convenience store on Nob Hill, and sometimes after nursery school, my mother would drop me there so she could run errands. I became enamored of a product they sold called Binaca Blast, which tasted like candy but also like medicine. Drop by drop, I wanted to consume the entire bottle of icy freshness, feeling it explode on my tongue. One time I had slugged down the contents of my aunt’s bottle laying next to the cash register, then I reached up to the display and pulled a new one right off the metal rod. I threw its cardboard package into the garbage can and indulged my minty jones until my mother came and picked me up.

The next day, when I was dropped off at the store, the tension was so thick you could cut it with a knife. My aunt called me up to the back room for a “talk.”

In the room there was a bare lightbulb swinging above my head. I was only three, but I knew an interrogation when I saw one.

“I know that you took that breath freshener. I want you to know that is ‘stealing.’ If you ask me, I will give you anything you want. But ask me first. Don’t steal. Stealing is bad. Okay?”

“But I wasn’t stealing.”

She looked at me hard.

“Oh really? Now, it’s okay. I’m not mad. But just don’t do it again.”

She gave me a hug and sent me back downstairs. I looked on the table, and there it was—the crumpled up cardboard packaging of Binaca Blast confirming my guilt.

The lesson I learned that day was to destroy all the evidence. As I lay in my crib, which was much too small for me, barely accommodating my head as I angled my feet up to the top of the bars, I played the incident over and over in my mind. I saw myself getting the Binaca Blast, tearing it out of the package, carefully gathering up the cardboard and the plastic, carrying it outside, looking around to make sure I had no witnesses, then dumping it in the trash can down the street, and running back into the store to enjoy the adrenaline of getting away with the goods. The spooky thing is I would always wake up in the morning with minty fresh breath.

I was enrolled in Notre Dame Nursery School, which was run by nuns. Being a known hustler did not win me much favor with the sisters. Most days, I found myself in Mother Superior’s office for my involvement in daycare crimes such as fingerpainting my neighbor and crawling around on the floor with an older man, a boy of five, during nap time.

Mother Superior’s chambers were dark and cool, and even though the nuns would threaten me all day long with being sent there, nothing ever happened when I arrived. Mother Superior would just nod her wimpled head and smile up at me through her glasses like Ben Franklin.

We had a Christmas pageant, and all the kids in the school were involved in a grand-finale number, singing a song for the Virgin Mary. The nuns kept saying during rehearsal, “When you see your parents out in the audience, don’t wave. Do you hear me? Don’t wave. If you wave, Jesus will be mad you messed up His song. Don’t wave. If you wave, you will go to Hell. Don’t wave. Don’t wave.”

When I went out on the stage, I saw my mom and my aunt in the crowd and they started to wave wildly! What could I do? I was having a moral dilemma. I kept seeing the nun’s face in my mind’s eye

(“Don’t wave . . . don’t wave . . .”)

, but here was my mom and my aunt doing just that! I couldn’t leave them hanging! In slow motion, my hand went up. It was like it wasn’t even attached to me. I couldn’t control it. It just started to move back and forth, and before I knew it, I was waving. My partner-in-crime, the boy of five, saw what I was doing and was not about to let me lead the revolution all by myself. He started to wave at his parents in the front row, who of course waved back, setting off another little kid and his parents and another and another. Pretty soon, the entire audience and all the kids on stage were waving at each other like we were on a float! Unfortunately, this was no parade. It was total Christmas-pageant anarchy and no one was even sure what to sing anymore and the nuns rushed us off the stage.

I thought I would be in trouble, but then when the pageant was over, we were let off for winter break, and by the time we got back, nobody remembered what happened or who waved first or anything. I was a bit disappointed that it was forgotten so easily, but I learned something very important that day: When you are on a stage and you wave, people wave back. This information would become very important for me later on.