I'm Just Here for the Food (45 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Chance favors only the prepared mind.

—LOUIS PASTEUR

ROCKWELL

The relative hardness or softness of a knife is reflected in the Rockwell of its metal. The Rockwell scale is a 100-point scale used to rate the hardness of minerals, metals, and ceramics. Diamonds have a Rockwell rating of 100. Most high-end HCS knives come in between 55 and 58, while carbon steel knives are softer, at 51. Some of the new ceramic knives on the market boast near diamondlike hardness, which their manufacturers claim gives them a longer-lasting edge. I find their lack of heft annoying, and the fact that they break like a plate when dropped is especially painful given their car-payment-like price tags.

Knives

I used to have a lot of knives: five or six boning knives, chef’s knives in every size from 4 to 14 inches, and even three or four different paring knives. Why so many? Because I didn’t know what I was doing and thought that my mediocre swordsmanship could somehow be improved by a great number of tools. Since I also didn’t know how to take care of knives properly, I spread the abuse out among the lot. Now I’m down to five knives. I use an 8-inch Asian-style cleaver, a semiflexible boning knife, a French-style paring knife, a serrated electric knife, and a 12-inch cimeter, which I mostly use to cut the backbones out of chickens and to break down large fish and beef sub primals. The cimeter and the boning knife are stamped-blade knives made by Forschner, the Swiss Army knife folks. The electric knife is specially made for fish cutting and came from a sporting goods store. It’s an ugly thing with a two-tone blue-and-gold chassis, but it has several different blades, two speeds, and it cost less than thirty bucks. My paring knife came from France and cost about thirty bucks. The cleaver was handmade by the only American-born master of Japanese blade making and cost more than two hundred smackers. If I had to choose one knife to live the rest of my cooking days with, this would be the one.

To be of real use a knife must be sharp, but it must possess the correct heft, shape, and balance for the job. Most of all, it must suit the hand holding it. Before you buy, you should know what you’re looking for (and at), how and from what it’s made, and the reputation of those who made it. Once you get it home, you should know how to store it, use it, and maintain it.

Metal Matters

When it comes to metal, there are basically two choices: carbon steel or alloys referred to as high-carbon stainless steel. Stainless-steel knives are widely available but impossible to sharpen, and quality knifesmiths never mess with the stuff unless they’re making pocket knives.

Steel is an amalgam of 80 percent iron and 20 percent other elements. In carbon steel, which has been around for quite a while, that 20 percent is carbon. A relatively soft yet resilient metal, carbon steel is easy to sharpen and holds an edge well. No matter what the knife salesman tells you, no high-carbon stainless-steel blade can match carbon steel’s sharpness. Carbon steel is, however, vulnerable in the kitchen environment. Acid, moisture, and salt will stain, rust, or even pit the blade if it’s not promptly cleaned and dried after each use. (You should probably pass on carbon steel when outfitting the beach house kitchen.) Slicing even one tomato with a new carbon steel knife will change the color of the blade. In time, it will take on a dark patina that some find charming, others nasty.

Most professional-grade knives on the market today are high-carbon stainless steel. This is an alloy of iron and carbon combined with other metals such as chromium or nickel (for corrosion resistance), and molybdenum or vanadium (for durability and flexibility, respectively). Although the exact formula varies from brand to brand, HCS knives possess some of the positive attributes of both carbon steel and stainless steel. The edge will never match that of carbon steel, but neither will it corrode. The trade-off is acceptable to the great majority of the folks who happily use them.

SUPER STEELS

More and more knife manufacturers are utilizing very complex and relatively expensive steel recipes called super steels, such as V610 and GS2. These metals seem to embody the best of all worlds: they can take an edge, keep an edge through rigorous use, and are stain-resistant.

KNIFE-BUYING TIPS

• Steer clear of sets. They may save you a buck or two but they’re rarely worth the savings. Besides, they usually come with knife blocks, which take up space and are impossible to clean. Even if you like blocks, don’t buy a set. You’re better off buying your blades one at a time so that you get exactly what you need.

• Shop around, prices vary widely.

• Never buy a knife that you haven’t tried out on a cutting board. If the clerk gives you flack about this, walk away.

HALF A DOZEN GOOD KNIFE RULES

1.

Stand comfortably when you’re using a knife.

2.

Hold the knife in such a way as to gain optimum control with minimum stress.

3.

Steer cutting not with the hand holding the knife, but with your other hand.

4.

Keep your thumb on your steering hand tucked back and feed the food into the knife with your knuckles. Or else.

5.

Always slice pushing forward.

6.

Whenever possible, work with the tip of your knife on your cutting board in order to stabilize a cut.

Construction

There are three ways to make a blade: forging, stamping or cutting, or separate-component technology (SCT). This is the arena where cutlery marketing departments duke it out. It’s also where you’ll find the greatest delineation in performance and price.

The best knives in the world are hot-drop forged. A steel blank is heated to 2000° F, dropped into a mold, and shaped via blows from a hammer wielded by either man or machine. The stresses of forging actually alter the molecular structure of the metal, making it denser and more resilient. Forged blades are then hardened and tempered (a process of heating and cooling in oil) for strength, then shaped, and handles are attached. This requires dozens of individual steps involving many skilled technicians, a fact reflected in the selling price. Once upon a time, all Wusthof-Trident, J. A. Henckel, Sabatier, Lamson, and Chef’s Choice knives were fully forged, but today most of these labels offer more economical stamped-blade lines too. If you’re looking to make a friend for life, full tang, forged knives are the only way to go. Of course, some friendships can be rewarding even if they don’t last forever.

A single forged piece of metal running from point to end of handle

Stamped, die-cut, and laser-cut knives have long been seen as inferior to forged blades. The blade and partial tang is stamped like a gingerbread man out of cold-rolled sheet steel. A handle is affixed, and away you go. Cost is the advantage here; the bad news is, without a bolster or full tang, heft, balance, and the molecular advantage of full forging are nowhere to be seen. However, because they’re quite thin, many chefs often prefer stamped blades for fish and boning knives, which are usually employed in such a way that heft and balance don’t really matter.

Separate-component technology is a new way for knife makers to get that great drop-forged look without going to all the trouble. SCT knives are pieced together from three separate parts. The blade and partial tang are stamped, then the bolster is formed from metal powder injected into a mold. SCT manufacturers claim this lets them use the perfect metal for each part rather than settling on one steel for the entire knife. The way I see it, even if the thing actually hangs together and even if the balance and weight are great, there’s still no way a stamped blade’s ever going to dice through the decades like a forged blade—it just doesn’t have the molecular muscle. These imposters are tough to spot, so you’ll have to find knowledgeable salespeople.

Maintenance

Most cooks who buy good knives ruin them within a year. Here are the best ways to accomplish this.

Store your knives in a drawer with a lot of other metal things.

Every time you open or close the drawer your edges will knock up against things that will bend/mangle/mash the fine edge into something resembling a tuna-can lid. Thus impeded, your blade will require a great deal of force to actually cut anything. And a dull knife with a lot of force behind it is about as safe as a shark with a chainsaw.

SHARPENING AND HONING

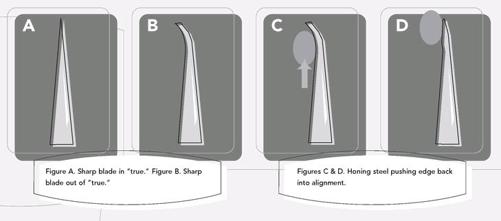

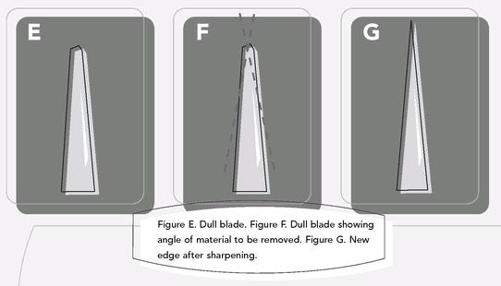

When a blade is sharp it looks like Figure A.

Given its thinness, it’s easy for the edge to develop microscopic bends, even with light use: Figure B. At this point the knife is still “sharp”; it’s just out of alignment and therefore not much good to the cook. Continued use at this point will only make things worse.

When frequently and properly applied, a honing steel, which is a good bit harder than the knife and is usually magnetized, can bring the edge back to “true” (Figures C & D). The key word here is “properly” and I’m convinced that (like shooting pool or writing poetry) this is one of those things that just can’t be taught on paper, as it requires the guidance of a skilled practitioner. My advice is to find a professional knife sharpener in your area who can sharpen your arsenal once or twice a year. Ask this person to sell you a steel the right size for your knives and show you how to use it.

I give a knife a stroke or two with the steel nearly every time I use it.

Wash your knives in the dishwasher.

If banging against plates (which have Rockwells far in excess of carbon steel) isn’t enough to do in the blade, the harsh chemicals of the wash and the ovenlike heat of the dry cycle will quickly grant your once smooth handle the topography of a dry lake bed. The fissures will soon fill with kitchen gunk—if the handle doesn’t fall off first.

Cut on a glass cutting board.

Just think of it: a metallic edge with an average Rockwell of 58 coming into repeated perpendicular contact with a surface with an average Rockwell of 98. I simply cannot imagine a better way to render a blade useless (See

Cutting Boards

).

Sharpen your knives yourself.

Sharpening devices are the darlings of the kitchen gadget industry, so you’ll have no trouble finding one in your price range to tickle your fancy. Count on the silliest-looking designs to effect the quickest destruction. As far as sharpening stones go, they may not look silly but they require considerable skill and experience to master and they’re a pain to maintain. Hone your knives often but never sharpen them—leave that to the pros.

If you use a honing steel, be sure to use it improperly.

If you need an example, find yourself a restaurant that has a big window that looks into the kitchen. Sometimes, when they know you’re watching, they’ll run their knife up and down the steel very rapidly. This is indeed horrible for the blade, but to the layperson it looks cool, which is why they do it.

TYPES OF CUTS

•

To mince is to cut food into very small pieces.