I'm Just Here for the Food (38 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

•

Many meat cutters hack the pieces apart instead of taking the time to separate them at the joints.

So in buying a whole bird you pay less money and get all those great pieces to make stock with. I make stock only a few times a year, so I bag, tag, and freeze the bones as I gather them. (A chest freezer in the basement is a wonderful thing.)

SURFACE TENSION

It was in 1751 that Johann Andreas von Segner, a German physicist and mathematician, first introduced his ideas about the surface tension of liquids. Today, we understand that molecules at the surface of a liquid attract each other to create something that’s been referred to as like a skin or a stretched membrane. (It’s because of this tendency that some insects are able to stand on the surface of a pond.) Water molecules are so attracted to each other that when presented with a different environment, such as air, they will shape themselves into spheres to expose as few molecules as possible to that environment. It’s easy to find an example of this phenomenon right at home in your kitchen. Check out a slowly dripping faucet. As the drops of water form, they sag or stretch out into almost a teardrop shape before falling.

Surface tension explains why pure water cannot be bubbled or persuaded to foam. And this goes not only for water but also for any pure liquid. To coax water into foaming, you have to break the tension by adding something that can work its way into the water.

Now here’s where the simmering comes in. You want to drop the heat as low as you can and still have a few stray bubbles breaking the surface. It’s not that boiling won’t do the job, it’s just that all that turbulence would break things up so much that you’d end up with a very cloudy stock.

How long to simmer? That depends on the volume of bones and water. I try to keep mine going for at least 8 hours, but then I’m greedy for the most gelatin I can get. You’ll know it’s over when you reach in with tongs and can easily crush the bones.

Big point: the more the water fills with gelatin, the slower the gelatin is extracted—the water gets “full” so to speak. So be sure to replenish the water as it evaporates from the pot, so that the original level of liquid is maintained. If bones are poking out the top, they’re not in the water, and they’ve got to be in the water if they’re going to do your stock any good.

When the bones crumble in the mighty grip of your tongs, it’s time to kill the heat and ponder your evacuation options. If you’re making only a gallon or two, you can probably safely lift the pot to the sink, but straining it is going to be a genuine pain. And remember, as we discussed in an earlier section, steam is a very efficient conductor of heat—and so are your arms.

Since stock can be kept in a deep freeze for up to a year when properly sealed, and I happen to have a chest freezer, I make stock only a few times a year—and when I do, I make a lot. And when I need to move it, I fall back on a skill developed in my misspent youth. Now, I’m not saying that I actually siphoned gas out of my parents’ cars so that I could fuel my Pinto and still have money for Big Macs, but . . . well, yes, that is what I’m saying.

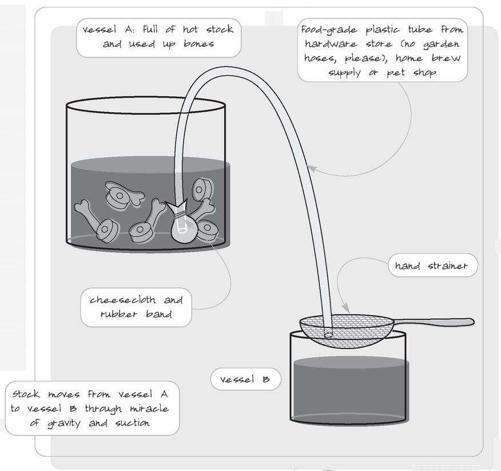

Find a heavy rubber band (the type that markets put on bunches of broccoli works well) and use it to attach a single layer of cheesecloth over one end of a 6-foot length of ½ to 1-inch food-grade plastic tubing (see illustration, right). I use stuff from the hardware store, but if you want to be super safe, buy food-grade tubing at your local home brewer supply. (If you live up north you can use the same tubing that folks use to hook up their taps during maple season.)

Place another pot (if you can, go with one as big as the one you’re siphoning from) at a lower level (in the sink, perhaps, with the pot of stock sitting on a hot pad on the counter). Set a fine-mesh strainer in the mouth of the empty pot. Hold the open end of the hose (without the cheesecloth) in your hand and, being careful not to block the opening to the pot, feed the cheesecloth-covered end of the hose into the pot of stock. Get as much of the hose in as possible; since the tubing was kept on a spool forever, it’ll probably help you out by coiling like a snake.

When you have at least two-thirds of the hose submerged, use your thumb to block up the end you’re holding and slowly extract the tube, making sure that the cheesecloth end stays all the way at the bottom of the pot.

Pull the tube down and hold it in the strainer. (I usually loop it under a rubber band on the handle so that I’m not stuck trying to hold both ends of the tube in their respective spots.) Now remove your thumb and behold. As long as you don’t let the end of the hose that’s submerged in the stock come to the surface, gravity and suction will transport the stock through the cheesecloth to the clean pot. (Yes, you can achieve the same end by sucking on the pipe, and yes, this is what I actually do, but neither me nor my publisher has any desire to be sued just because somebody gulps a big ol’ mouthful of hot stock.)

Now take a look at the stock you’ve managed to move. If it seems relatively clear you don’t have to strain further, but I usually do. Take four layers of cheesecloth and attach them to a colander with a couple of clothespins and strain into another container, preferably one with a lid.

Take a spoon and give the final liquid a taste. Feels kind of funny in your mouth, huh? Not thick, necessarily, but “full,” with lots of body. That’s the gelatin. Note the subtle chicken flavor. It’s not overwhelming, and that’s good because this stuff is going to work in a lot of different dishes and you wouldn’t want everything to taste like chicken.

Now we switch to sanitation mode. You have a big bucket of germ food sitting there in the

Zone

, and that just won’t do. Put the container in the refrigerator and not only will it take forever to cool down, but everything else in the fridge will get hot.

If it’s cold out, lid up the container and set it in the carport or garage until the temperature of the stock drops to about 40° F.

If it’s not cold out, fill a heavy zip-top freezer bag with ice, seal it carefully, then float it in the stock. As soon as the ice melts, remove the bag, drain, and refill with more ice.

33

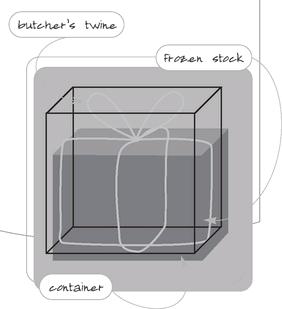

Once the stock is cool there are more options. I usually freeze four or five ice cube- trays full. These stock blocks will be moved to freezer bags and used to mount sauces on down the line. The rest of the stock goes into 1-quart plastic containers. (I’m a Rubbermaid man, but Tupperware is darned fine, too.) The important thing is that the container be shaped so that a giant stocksicle can slide right out.

“It’ll never slide right out,” you say? It will if you lay a piece of butcher’s twine or dental floss (unflavored, of course) down one side and up the other (see illustration). Think of it as a ripcord for the frozen liquid of your choice.

Now what? Well, now you’ve got a full-bodied, flavorful liquid for any occasion. That pot of collards we were talking about? Use stock instead of water. And soup—everything in the kitchen can be soup if you have stock around. The best soup I’ve ever tasted was composed of leftover mushroom risotto, seared chicken thighs, parsley, and homemade chicken stock . . . delicious.

Pan Sauces

I blame the demise of pan sauce-making on non-stick pans. Sure, I’ve got a few myself but I only use them for eggs, crêpes, that sort of thing. The problem is that non-stick pans do not work with you when it comes to sauce making. Steel and iron pans are the sauce maker’s friend because stuff sticks to them and that stuff is called

fond

.

Fond

is (of course) French, but the word derives from the Latin

fundus

, meaning “bottom” or “property.” In modern usage it means the basis or foundation of something—as in a sauce.

Say you seared a steak in a pan, or roasted a pork loin in a roasting pan. Once you pull the meat from the metal, you notice that the bottom is covered with a dark and no-doubt nasty crust. Your first instinct is to toss that pan in the sink to scrub later. That would be a shame.

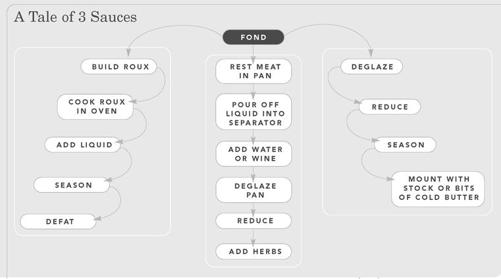

The first step to converting that grimy crust to a sauce is to decide what to do with any fat in the pan. You basically have two choices: build a roux or defat the pan. If the beast in question is a turkey or a roast that might be nice with a gravy, you would go the roux path, which we’ll get to shortly.

A juicy flank steak or porterhouse, on the other hand, is not something that screams “gravy.” There is enough richness in such meats to satisfy the tongue, so you’re better off with a “lean” pan sauce, or one that has been finished with a little butter or an aged cheese like gorgonzola (or both, see

Blue Butter

). Unless you seared an incredibly lean piece of meat, odds are good that some fat exited from it and is hanging around the pan. If you pan fried or sautéed something—say, turkey cutlets—then there will definitely be a good bit of fat left hanging around.

Fat gets in the way of deglazing, that is, to add liquid to the hot pan in order to loosen and dissolve the browned bits of goodness stuck to the bottom of said pan.

34

Most recipes suggest simply burning off the fat, but that will probably send a lot of great-tasting juices with it. There are three strategies:

1. Pour off the fat, sacrifice the liquid, and live with it. You’ll still be able to deglaze but oh, what a waste.

2. Allow the cooked meat to rest on a resting rack so that you capture any and all juices. Then remove the meat and place the bowl in the freezer for a few minutes. The fat will lift right off and you can return the juice to the pan.

3. My favorite method, especially for poultry, is to rest the meat in the pan, and then drain the collected liquid into a gravy separator. Add enough water and/or wine to the liquid to lift the oil well above the spigot of the separator. Then I use this liquid to deglaze the pan. Reduce by half over high heat and add a handful of parsley for the final minute and you have a simple, fresh

jus

.

What other liquid should you use to deglaze the pan? As long as it’s a water-type liquid, the sky’s the limit. Alcohols, be it wine or bourbon or beer or cognac, are favorites because they:

• are water-type liquids;

• contain a lot of flavor; and

• contain alcohol, which can dissolve and impart alcohol-soluble flavor compounds to the sauce.

Other deglazing options include everything from tea to Perrier, but unless I’m just cleaning the pan, I avoid straight water because it doesn’t bring any flavor to the party whatsoever.

Add enough liquid to cover the bottom of the pan by about a ¼ inch.

Bring the liquid to a boil, scraping the pan often with a wooden spatula. Allow the liquid to reduce by half. By then anything worth keeping in the sauce will be dissolved. If no flour was involved in the cooking process you will be left with a thin liquid—not something that is going to cling to a forkful of meat and ride its way to your mouth. Here you have two choices. Add butter (tasty, glossy, thick, and fattening) or a touch of stock (tasty, glossy, thick, and fat-free). Or you can go with a combination of stock and a flavored butter like our

Herbed Compound Butter

. Add this, with perhaps some minced herbs, at the last possible moment, and stir or whisk to combine. You’ll be amazed at how a sauce appears out of nowhere.