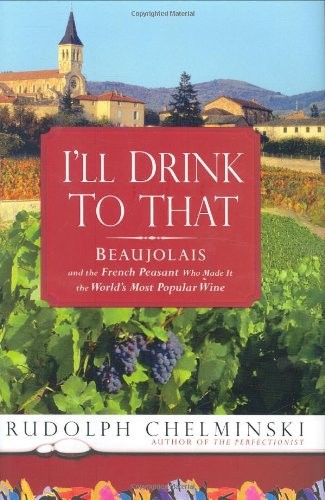

I'll Drink to That

Read I'll Drink to That Online

Authors: Rudolph Chelminski

Table of Contents

GOTHAM BOOKS

Published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.); Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England; Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd); Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd); Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India; Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.); Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published by Gotham Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First printing, October 2007

Copyright © 2007 by Rudolph Chelminski

All rights reserved

Gotham Books and the skyscraper logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Chelminski, Rudolph.

I’ll drink to that: Beaujolais and the French peasant who made it the world’s most popular wine /

Rudolph Chelminski.

p. cm.

Chelminski, Rudolph.

I’ll drink to that: Beaujolais and the French peasant who made it the world’s most popular wine /

Rudolph Chelminski.

p. cm.

1. Beaujolais (Wine)—French—History. 2. Duboeuf, Georges. 3. Vintners—French—Beaujo-

lais. 4. Wine and winemaking—France—Beaujolais—History. 5. Beaujolais (France)—History.

I. Title.

TP553.C378 2007

614.2’2230944—dc22 2007016024

lais. 4. Wine and winemaking—France—Beaujolais—History. 5. Beaujolais (France)—History.

I. Title.

TP553.C378 2007

614.2’2230944—dc22 2007016024

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

http://us.penguingroup.com

eISBN : 978-1-4406-1974-8

Foreword

When I began researching this book, I was struck by the remarkably consistent—I would even say uniform—reaction by friends and acquaintances upon hearing that its subject was to be the Beaujolais: first the smile, then the complicit burst of laughter and one of those you-lucky-guy remarks to signify that my undertaking was certain to be fun, but somehow not quite serious. A whole world of predigested assumptions underlay this reaction. With the subject of wine enjoying an unprecedented prominence and prestige (attended by its inevitable dance steps of protocol and snobbery), the general conclusion was that I had chosen to write a book about a Ford instead of a Ferrari. Everyone knows Beaujolais, or thinks he does, and everyone has an opinion, one that can usually be expressed within a few seconds. This opinion-giving is often wildly erroneous, but it is unfailing. After all, who has not tossed down a glass of Beaujolais at one time or another in his life, and who has not read an article about this or that aspect of its singular career? The saga of Beaujolais Nouveau alone erupts in such a yearly blaze of publicity that it can scarcely be avoided. For universal name recognition, the only wine that can rival Beaujolais is Champagne.

The name Champagne doesn’t elicit smiles and laughter, though, and neither do Bordeaux or Bourgogne—that’s

serious

stuff. For that matter, just about any wine you can think of, whether it be from Alsace, Languedoc, Midi-Pyrénées, California, Australia, Chile or anywhere else, will be assessed with similar poker-faced gravity. Only Beaujolais gets the smile and projects this aura of easy familiarity.

serious

stuff. For that matter, just about any wine you can think of, whether it be from Alsace, Languedoc, Midi-Pyrénées, California, Australia, Chile or anywhere else, will be assessed with similar poker-faced gravity. Only Beaujolais gets the smile and projects this aura of easy familiarity.

But familiarity breeds contempt, as we all know, and Beaujolais has suffered more than its share of obloquy. This, of course, is the ransom of its success, but it is really quite extraordinary that a success and a notoriety of this degree should have come to a wine that represents only slightly more than 2 percent of France’s total production and .05 percent worldwide. How it reached this point of celebrity is a story of a few turns of history’s wheel, of a certain amount of luck and a certain amount of marketing skill, but mostly of a long background of unremitting drudgery: centuries of hard work poorly rewarded. It is also to a great extent the story of one man, a young peasant winegrower named Georges Duboeuf who at age eighteen revolted against an unfair, illogical distribution system run for the benefit of a dealers’ cartel, and did it so well and so thoroughly that he rose to become the biggest dealer of all—but one of an entirely new style.

Beaujolais, then, is a double success story, the wine and the man, but does that make either worthy of being treated in full book length? After all, there are thousands of capitalists wealthier and more influential than Georges Duboeuf, and any number of Ferrari wines of greater prestige than Beaujolais. Naturally I answer an emphatic

yes

to the above question, because beyond the predictable angle of the underdog winning against the odds, the history of the Beaujolais reflects and explains a good deal about the French themselves, “this quick, talented, nervous, occasionally maddening but altogether admirable people” (I’m quoting myself here), among whom I have lived for more than forty years now. As for Georges Duboeuf, capitalism would have an infinitely better reputation today if all the world’s Enrons, Tycos and WorldComs had been run by the likes of this model entrepreneur.

yes

to the above question, because beyond the predictable angle of the underdog winning against the odds, the history of the Beaujolais reflects and explains a good deal about the French themselves, “this quick, talented, nervous, occasionally maddening but altogether admirable people” (I’m quoting myself here), among whom I have lived for more than forty years now. As for Georges Duboeuf, capitalism would have an infinitely better reputation today if all the world’s Enrons, Tycos and WorldComs had been run by the likes of this model entrepreneur.

More than any other factor, the sudden worldwide prominence that came to the wines of the Beaujolais is owed to Duboeuf. He’s a very interestingcase, one of those rare persons inhabited by a mysterious kind of driving force that sets certain individuals apart from the rest, causing them to achieve what others don’t even think about venturing. We all come across a few of them in the course of a lifetime, and can never quite define what that force is or why it should be there, but it is always clear that it

is

there: he or she is simply different. Georges Duboeuf’s rise from modest station to wealth, repute and influence is like the plot of a Thomas Hardy novel, and it is no accident that this rise coincided exactly with the progress of the fortunes of the Beaujolais country and its wines.

is

there: he or she is simply different. Georges Duboeuf’s rise from modest station to wealth, repute and influence is like the plot of a Thomas Hardy novel, and it is no accident that this rise coincided exactly with the progress of the fortunes of the Beaujolais country and its wines.

For the sake of form, let me establish something right away, lest I be accused of partiality: I count Georges Duboeuf as a friend. I am partial. I am partial to Georges because of his admirable personal qualities—integrity, sincerity, constancy—and for having served as my initiator and guide to the Beaujolais. He generously shared with me his unparalleled knowledge of and love for the country, its people and, of course, its wines, allowing me to partake at least modestly of that knowledge. In his company I explored the back hills, the villages and hamlets and vineyards, and through him I had the luck to become acquainted with the extraordinary, colorful and always engaging human fauna that peoples this beautiful little slice of the French countryside.

Because my expeditions with Duboeuf were not mere tourism. Georges introduced me to an entire gallery of the dramatis personae of the Beaujolais. A short selection would have to begin with the vigneron (winemaker) Louis Bréchard, known everywhere by the sobriquet “Papa,” sage and folk historian of the Beaujolais, a man who carried his wisdom all the way to parliament in Paris when he was elected deputy in 1958. Count Louis Durieux de Lacarelle, owner of the biggest single estate in the Beaujolais, presides over his vines, his wine cellar and his lunch table with the melancholy bonhomie of the aristocrat who has seen just about all the world has to offer and, everything considered, prefers his little château in the Beaujolais-Villages country of Saint-Étienne-des-Oullières, where he can follow Voltaire’s advice and cultivate his garden in peace. Gérard Canard and Michel Brun were and are passionately devoted professionals of promotion who cheerfully spent their lives spreading the Beaujolais gospel around the globe. (Brun carries his regional loyalty to the point of awarding himself the e-mail address of Michelgamay, appropriating the name of the Beaujolais grape as his personal identity.) Edward Steeves is a poetically inclined Yankee scholar from Boston, a rare and true gent who fell so deeply in love with the wine, the land and the people of the Beaujolais that he settled there, married, produced three Franco-American children and became boss of an important wine distribution house. He will learnedly expatiate at the drop of a hat, in French, English, Latin or Greek, on the relative virtues of Chiroubles, say, as compared to Saint-Amour, Régnié or Chénas, and he does it so well that he is in constant demand as a keynote speaker who politely and convincingly informs the natives about their own wines. Marcel Laplanche and Claude Beroujon, winemakers of the old school, can recite from memory the exact weather conditions of any year from about 1930 onward, how the wine tasted and what price it fetched. My friend Marcel Pariaud is so stricken with the peasant’s reluctance to throw anything usable away that at last count he owned seven tractors, none less than forty years old. (“But they all work!” he protests when I josh him about it.) In spite of this rich collection of mechanical antiquity, though, he prefers to do his plowing behind Hermine, his indolent Comtoise workhorse. With her cooperation, Marcel wrings from the soil in and around the village of Lancié a Beaujolais and a Morgon so perfect that you immediately understand why the people of the region stay away from water. And of course there was everybody’s favorite, René Besson, “Bobosse” the

charcutier

, sausage maker to kings, the joy and sorrow of the Beaujolais—First-Class Drunkard, as he liked to qualify himself, the laughing, overwhelmingly generous lover of life and good companionship over a shared glass or two or ten, Falstaff to Duboeuf’s Prince Hal. Bobosse refused to accept that our short mortal route was but a vale of tears, and he more or less drank himself to death by enjoying the ride too much. Naturally it is impossible to defend irresponsible behavior of this sort in a rational world, but it wasn’t rationality that guided Bobosse’s life. Where drinking was concerned, he was an

artiste

, and his creativity in expressing his art was Platonic—at a low-flying level, to be sure, but Platonic all the same: divine madness. Everyone knows it must be banned from the city of the sensible, but, lord, how graciously he carried it off.

charcutier

, sausage maker to kings, the joy and sorrow of the Beaujolais—First-Class Drunkard, as he liked to qualify himself, the laughing, overwhelmingly generous lover of life and good companionship over a shared glass or two or ten, Falstaff to Duboeuf’s Prince Hal. Bobosse refused to accept that our short mortal route was but a vale of tears, and he more or less drank himself to death by enjoying the ride too much. Naturally it is impossible to defend irresponsible behavior of this sort in a rational world, but it wasn’t rationality that guided Bobosse’s life. Where drinking was concerned, he was an

artiste

, and his creativity in expressing his art was Platonic—at a low-flying level, to be sure, but Platonic all the same: divine madness. Everyone knows it must be banned from the city of the sensible, but, lord, how graciously he carried it off.

Denizens of the Beaujolais country like these bear little resemblance to the edgy, ill-tempered Parisians through whom tourists often form lasting opinions of the French national character. One taxi ride from Charles de Gaulle Airport to the center of the capital can be enough to set a negative impression into stone, and that’s a shame, because the impressions would be utterly different if these same visitors ever took the time to pass by way of the Beaujolais country. There they would be able to appreciate how inaccurate the tired old stereotypes can be. Contrary to the popular (and largely Anglo-Saxon) legend of Latin hedonism, three-hour lunches and nonstop sexual dalliance, the French are an extremely industrious and hardworking nation with a long tradition of perfectionism in artisan craftsmanship, and few crafts can represent this tradition—vibrant today still—better than that of the individual peasant winegrower.

Beaujolais is the smallholder wine country par excellence. Unlike their wealthy Burgundy and Bordeaux cousins who specialized in winemaking very early in their history, the peasants of the Beaujolais were until quite recent times primarily subsistence farmers who grew grain and tended animals to survive while making wine as an aleatory cash crop. Theirs was a punishing, penurious existence, and most of them remained stuck in anonymous poverty until after the Second World War. That very poverty and relative humbleness of condition, though, made them solid representatives of

la France profonde

, the obscure rural masses at the country’s heart, whose life experience and peasant wisdom formed much of the national character as it stands today.

la France profonde

, the obscure rural masses at the country’s heart, whose life experience and peasant wisdom formed much of the national character as it stands today.

Other books

Arianna's Tale: The Beginning by D. J. Humphries

The Portrait by Megan Chance

Dead Clever by Roderic Jeffries

Mrs. Pollifax on Safari by Dorothy Gilman

Wings of War by John Wilson

Carrie's Montana Love: New Montana Brides (New Montana Bride Series) by Susan Leigh Carlton

The Cup of the World by John Dickinson

Ménage by Faulkner, Carolyn

Searching for Beautiful by Nyrae Dawn

Sleeping With the Enemy by Tracy Solheim