IGMS Issue 50 (10 page)

Authors: IGMS

"I guess it's a kind of fame," Debra said unenthusiastically, her arms wrapped around a pillow. She waited while the little two-way screen stayed blank. With the tiny door to her sleep compartment closed, their conversation was exclusive.

"I'm sorry," the boss's image said. "I suppose I sound like an ass, going on about ratings when you and the crew are making a life-or-death decision. You should know that I've already told Pakinski he has my full support to turn things around and come on home. I love the fact that you're the talk of the Earth right now, but that doesn't mean I think you should sacrifice yourselves for the sake of my ambition. Really, at this point, the trip has already accomplished everything I could have ever hoped--and a whole lot more. There'd be no shame in coming back early."

"Easy for you to say," Debra replied, "you're not the one who has dreamed of going to other worlds since she was a little girl. I'm pretty sure Pakinski and the rest of us know that if we turn around now, there won't be a second chance. Yeah, the Apollo 13 guys were heroes, but Jim Lovell never flew in space again, and neither Fred Haise nor Jack Swigert got a chance to fly on future moon missions. Ratings for

Determination's

flight might be amazing now, but if we turn around, people are going to call us quitters. Viewers will get bored and drop out. Along with the advertisers and their dollars."

More minutes of black air.

"Hey, look," the boss said finally, "if I were in your place . . . I am honestly not sure what I'd do. I agree with you and Pakinski: It's got to be a unanimous vote. Hopefully, everybody has cooled off enough to be able to see the big picture. Just let no one say Ben Groomer forced you to continue against your better judgment. I'd rather have you back alive than marooned permanently in Jupiter orbit. I'm a man who likes to think and dream big--but not at the expense of other peoples' futures. I'll wait to hear from you all. And I will support whatever final call is made."

The screen went black, this time for good.

Debra closed her eyes again, and waited for sleep to take her. Certainly it had been an exhausting few days since the initial accident. She should have faded right out. But when she didn't, and when the silence of the sleeping compartment became more than Debra could stand, she decided to pay the ship's tiny observatory a visit.

Debra found that she had not been the only one with the same idea. Almost everybody aboard had come--against Pakinski's orders. They were all staring at zoomed-in images of Jupiter, and Jupiter's many moons. This far from Earth, the pictures were spectacular. Better than anything any telescope on Earth could capture, and also better than anything any space probe had yet sent. The color in the banded clouds was stunning. The Great Red Spot was more distinct and impressive than it had ever been before. The surfaces of Callisto, Europa, and Io beckoned.

Nobody was arguing. They weren't even talking. They were all just staring.

Debra chose to look out a porthole. To the naked eye, Jupiter was a uniquely bright point of light, the chief star in

Determination's

sky. Debra kept her eyes on that unmoving, unblinking point until she turned away and pulled out one of the keyboards attached to the observatory's main computer array. She rapid-typed, ordering one of the

Determination's

many telescopes to face back the way they'd come. Searching on automatic for a pale, blue dot.

Having acquired the target, Debra overrode one of the biggest screens in the observatory, thus showing a magnified image of the Earth and the Moon together in space. Small. Delicate. A unique pair in the solar system. Perhaps, even, in all the galaxy?

In ones and twos, the heads of the crew turned away from the images of Jupiter and focused on their mutual home. Like before, there was no sound. Peoples' faces slowly passed through a range of different expressions, and a few tears began to leak from the corners of several different pairs of eyes.

A voice suddenly broke the calm. It was Pakinski's, from the open hatch at the back of the observatory. How long he'd been there, nobody knew. He'd come upon them silent as a cat. His face was sad.

"Well . . . we sure did give it one hell of a try," the captain said.

Debra found herself nodding vigorously, her vision obscured by tears, her heart breaking.

Debra had been right. Viewers and advertisers did drop off. And yes, there were people who called the crew of the

Determination

quitters. But these voices were few and far between. Even the most die-hard space exploration enthusiasts couldn't bring themselves to criticize the crew for turning away from probable suicide. Coming back was the sane man's choice. And during the long, slow deceleration, alteration of trajectory, and acceleration burn--to hasten the

Determination's

flight toward its ultimate arrival--there was a new conversation happening back home. A conversation nobody had expected. Least of all Debra herself.

"I was approached by a consortium of industrial investors," Ben Groomer's message said, this time, to the whole

Determination

crew while they ate in the ship's small galley. "These aren't bit players, either. They're people with serious money and serious assets at their disposal. I think your crisis aboard the

Determination

finally got these folks off the fence. They said they want to arrange for a second, even more ambitious trip. With a bigger, even better ship. Using all the lessons we've learned from the

Determination's

voyage.

"I've already got engineers doing back-of-the-envelope sketches. We're putting a nice, wide, thick bow shield on the front of the new ship. Stupid that we didn't think of it for the

Determination.

Maybe if we had, your predicament might not be so bad. And for which I am truly sorry.

"Look, everybody, I don't know if the words of an old business hustler mean anything to pioneers like you, but I am grateful from the bottom of my heart for all you've accomplished. For going as far as you have. Things back here on Earth . . . well, the show isn't just a show anymore.

Everyone's

talking about what comes next. For Jupiter. For Saturn. People are saying it's not fair that

Determination

didn't make it. That we have to try again, and keep trying."

For Debra, it was a curious turn of events. Could there be such a thing as a successful failure? She'd grown up watching the United States space program fall prey to disinterest. She'd dreamed of finding a way to make people

care

again. And while she'd gone all-in with Groomer's suggestion that she be aboard for the ride, losing Jupiter in the short term might mean gaining a whole lot more in the long term. Her email box was now flooded with requests: from universities, corporations, government and military contractors, as well as space clubs and advocacy groups, all asking her to come and present for them. To speak about her experience. To tell them about the

future.

"It's what I wanted, sort of," she told Ben Groomer one evening, just before bed. "Ten years ago, nobody was even talking about going back to the Moon. Now? Now it seems like everyone is getting excited again. To come out here. After so long."

"You know, I never told you why I joined the Navy," Groomer said, following a delay which had grown noticeably shorter of late. "See, when I was a little kid, they had this show on TV called

Star Trek.

And I wanted to be part of that show so bad--I mean, for real--that when the time came for me to grow up and go out into the world, I joined the closest thing to

Star Trek

I could find. And no, the Navy didn't live up to my hopes in that regard. But I always imagined, when I was out at sea, how some day--some day!--people would be standing on the decks of ships going between the planets, and then the stars too."

"The

stars?"

Debra said.

"Oh, without question!" Groomer said happily. "Give it time. A couple of centuries, I'd bet. Maybe less. Could that reactor design of yours be adapted for interstellar use?"

Debra thought about it for a few minutes, doing some math in her head.

"You'd need a reactor far, far bigger. And even more efficient. With a lot more fuel. The ship would be

immense.

Far larger than anything we've ever built before. By an order of magnitude, or more."

"But in theory, it could be done?"

"Yes, Ben, I think it could be done."

"Well, then, even if I am not around to see it, I hope it happens one day."

"Me too," Debra said, smiling.

"You gonna still work for me, when you come back to Earth?" Ben asked.

"Oh, probably. After I feel like I've done enough, out there on the road. Your junk food TV show has turned me into something of a commodity. I've got speaking engagements lined up forever. People seem to think I've got my finger on the pulse of what our destiny in space looks like."

"It couldn't have happened without your reactor," Groomer said.

"We

both

did it. You had the cash, I had the design, and we both had the desire."

"And apparently a lot of other people had that desire too," Groomer said. "They just needed someone crazy enough to show them the way. That somebody was

doing

something."

The smile lines around Groomer's eyes crinkled delightfully.

"I was thinking," Debra said, "about the new ship."

"Yeah?"

"She needs a worthy name. How about calling her

Persistence?"

"Only if you'll volunteer to break the champagne across her bow. Deal?"

"Deal," Debra said, catching herself smiling.

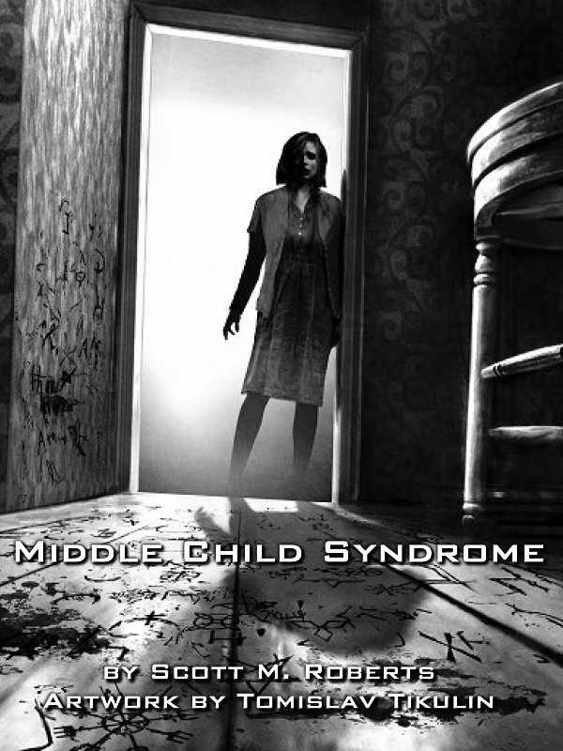

by Scott M. Roberts

Artwork by Tomislav Tikulin

Tara found the first scrap of paper on the running trail. It spiraled out of the trees and landed on the path just in time for her to run over it with Zandy's stroller.

"Trash!" Zandy cooed. "Trash, Mama! Trash!"

"Trash, right," Tara said. And because she'd spent

hours

lecturing Zandy and the boys about litter, now she'd have to pick it up.

The paper was warm. The top right corner was charred, and when she ran her thumb over it, bits of blackened ash smeared her fingers. It didn't surprise Tara that someone was starting fires out here in the undeveloped areas behind the neighborhood. Teenagers, probably. Lots of dry wood lying around, an unseasonably warm Friday afternoon in April--the most natural thing in the world for dumb, hormone-afflicted kids to do was to goof around starting fires in the secluded woods and marshlands.

Now that she stopped and sniffed, there did seem to be a smell of burning in the air. Tara peered through the trees to see if she could see any smoke. Seeing smoke would mean she would have to

investigate

--like an upstanding, HOA-dues-paying member of civilization. And if she found someone starting fires, she'd have to fuss at them, and probably call their parents if she knew them, and then worry about whether the little arsonists would come after her for revenge, and all she had ever wanted to do was go for a jog with Zandy.