If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (5 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

As male doctors gradually took over more of the responsibility for delivering babies from the midwife, the design of the birthing chair began to change. A lower chair is better for a woman giving birth, as she can brace her feet against the floor. Its drawback is that the midwife has to bend down low, ‘always leaning forward and bent over, with hands stretched out, watching for the foetus to appear’. But from around 1700, when doctors began to take over, birth chairs started to have longer legs. These higher chairs meant the physicians didn’t need to stoop, but they were less comfortable for the woman. Eventually mothers were encouraged to lie down flat on their beds and push, instead of to sit and use gravity. It strikes one as being more to the benefit of doctor than patient.

A seventeenth-century birthing chair from the Wellcome Collection, London

Pain relief in Tudor times lay in the power of

prayer. Westminster Abbey’s ‘Girdle of Our Lady’ was sometimes lent by its abbot to ladies in labour, such as Henry VIII’s sister Mary Tudor. They might also turn to recipes such as John Partridge’s optimistically named herbal potion ‘to make women have a quick and speedy deliverance of their children, and without pain, or at least very little’. Georgian ladies could rely on the rather more efficacious ‘liquid laudanum’ – opium dissolved in alcohol. It was completely legal, and Dr John Jones’s

The Mysteries of Opium Reveal’d

called the drug ‘a sage and noble panacea’. Queen Victoria popularised the use of chloroform during birth, but did so in the face of enormous moral pressure not to ‘succumb’ to this ‘weakness’. Many of her subjects thought that ‘to be insensible from whisky, gin, and brandy, and wine, and beer and ether and chloroform, is to be what in the world is called Dead-drunk’, something shameful whatever the circumstances. However, the rational and scientific Charles Darwin administered chloroform to his own wife himself during her labours.

Even after people began to understand that invisible germs might be carried into a bedroom upon seemingly clean hands, there was great opposition among doctors to changing their habits. In 1865, the Female Medical Society asked that doctors refrain from coming straight from the dissecting room to the birthing room, but a riposte in

The Lancet

claimed that it was entirely unnecessary: it was not infection but a woman’s ‘mental emotion’ or overexcitement that caused puerperal fever. The Tudor practice of remaining in bed after the birth was still followed: a book entitled

Advice to a Wife

, published in 1853, recommended that a new mother should spend nine days on her back before she ‘may sit up for half an hour’. Only after a fortnight might she ‘change the chamber for the sitting room’.

There was, of course, a distasteful class aspect to all this resting up and seclusion. Another Victorian advice book claims that it is ‘utterly impossible for the wife of a labouring man

to give up work … Nor is it necessary. The back is made for its burthen.’ For working women, or among the settlers in the New World, there was an unresolved tension between motherly and wifely duties. A mother-to-be was medically advised not to lift her arms above head height, yet reaching upwards was essential for the typical New England wife’s task of daubing an unfinished or leaking house with clay. When Margaret Prince of Gloucester, Massachusetts, appeared in court to accuse a neighbour of casting a harmful spell upon her stillborn child, the ‘daubing’ accusation was thrown back at her. Yes, she had done ‘wrong in carrying clay at such a time’, Margaret admitted, but ‘she had to, her husband would not, and her house lay open’. There was clearly a need, in rural societies, for pregnant women to carry on just as usual.

The squeamish attitudes of the nineteenth century introduced a novel reluctance to talk about pregnancy. As early as 1791, a writer in

The Gentleman’s Magazine

noticed a growing trend for references to pregnancy to be seen as errors of taste. ‘Our mothers and grandmothers, used in course of time to become

with child

,’ he wrote, but ‘no female, above the degree of chambermaid or laundress, has been with child these ten years past … nor is she ever

brought to bed

, or

delivered

’. The genteel lady should merely inform ‘her friends that at a certain time she will be

confined

’. The downside of all this tasteful gentility was that women began to think of pregnancy as an illness, and Victorian books about childbirth began to refer to it among ‘the diseases of women’. In the bedchamber, as in society at large, women began to be seen as fragile, vulnerable and incompetent at looking after themselves.

This was a great change from the more robust attitudes of the Georgian period, which saw a cruder but in some ways more assertive attitude amongst women to matters of sex and reproduction. Queen Caroline, wife of George II, would openly discuss her sexual relationships with the prime minister, Sir Robert

Walpole, and stated that she minded her husband’s infidelity ‘no more than his going to the close-stool’.

One cannot imagine prissy Queen Victoria ever discussing such a matter with her prime ministers. She herself was horrified by the experience of giving birth to children – ‘the first two years of my married life [were] utterly spoilt by this occupation!’ – and she almost certainly suffered from post-natal depression. Secrecy about childbirth only heightened the fears of the uninformed, first-time, nineteenth-century mother, and a reticence about women’s bodies could be inconvenient if not downright dangerous. From the 1830s, for example, doctors knew that the mucosa of the vagina changed colour after conception, and this signal provided the earliest reliable indicator that a woman was pregnant. This would have been enormously useful for women to know. But the information was kept quiet because it implied that a doctor might actually examine a woman’s private parts. The doctor who finally broke ranks and published the news was struck off the medical register as a punishment.

Alongside the idea that pregnancy was an illness, the lying-in hospital began to grow in popularity. Slowly childbirth was taken out of the bedroom, out of the home altogether, and into the public realm.

A rather sinister account of childbirth written in 1937 describes what happened, in ideal circumstances, when the expectant mother arrived at the twentieth-century hospital. She was ‘immediately given the benefit of one of the modern analgesics or pain-killers. Soon she is in a dreamy, half-conscious state … she knows nothing about being taken to a spotlessly clean delivery room … she does not hear the cry of the baby when first he feels the chill of this cold world.’ It didn’t work out like this for Mira, the heroine of the

The Women’s Room

(1978): ‘It was not the labor that was agonizing her … it was the scene – the coldness and sterility of it, the contempt of the nurses and the doctor, the humiliation of being in stirrups

and having people peer at her exposed genitals whenever they chose.’

Today, as a result of this sort of experience, many people would like to see childbirth return to the domestic realm. But New York midwives are, at the time of writing, not legally allowed to deliver babies in people’s homes.

Another maternal duty that Queen Victoria avoided was the task of breastfeeding. In fact, it was much less common than you might assume in historic bedrooms, as a result of the once widespread practice of wet-nursing.

3 – Was Breast Always Best?

I am quite at a loss to account for the general practice of sending infants out of doors, to be suckled … by another woman.

William Cadogan, 1748

For many centuries, breast was not best for upper-class women, and newborn babies were often quickly expelled from their mothers’ bedrooms.

The early care of infants was considered vital, of course, to their future well-being, and well-brought-up children required a huge amount of clobber. Hannah Glasse, the eighteenth-century Gina Ford, recommended that a baby wear a minimum of a shirt, a petticoat, a set of buckram stays, a robe and two caps. It seems almost cruel to squeeze a baby into tight stays, but it was intended to ensure a straight spine. Those who grew up crooked were thought to owe ‘their misfortune to the disingenuity of those who attended them in their infancy’, who’d shamefully failed to lace them tightly enough.

Childcare was clearly a matter requiring expert skill and attention. And yet, for centuries, mothers did not consider that they were the best people to care for their children.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were a golden age of wet-nursing.

Much of the evidence for this comes from one very vocal campaign group that complained vociferously about the almost universal use of wet nurses, and there was great debate on the issue (just as there is for breast- and bottle-feeding today). Only a very few ladies of ‘courage and resolution’ nursed their own children, it was said in the seventeenth century, and a nursing mother ‘is become as unfashionable and ungenteel as a gentleman that will not drink, swear and be profane’.

But the complainers who preached so loudly on the topic were usually rather officious godly gentlemen of the Puritan persuasion. Even mothers whose milk had run dry did not escape their censure: ‘sure if their breasts be dry, as they say, they should fast and pray together that this curse may be removed from them’. These views naturally held great sway in the Puritan communities of New England. In contrast to Britain, breastfeeding became the norm there at all levels in society.

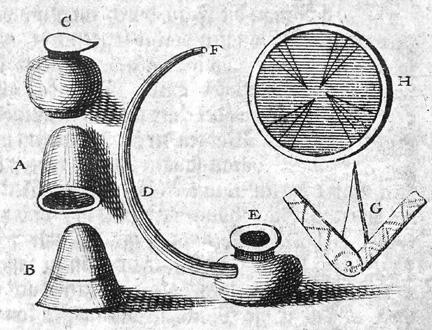

A seventeenth-century breast pump

While some women were incapable of providing milk, there

were certainly many others who just wanted to avoid pain and inconvenience. A significant group were forbidden by their husbands to breastfeed because it inhibited the conception of the next child. Certainly a woman of property who’d given birth to a girl would be expected to return to the marital bed as soon as possible in the hope of providing a male heir to the family’s estates.

Bernardino Ramazzini (

c

.1700) gave a list of medical risks to the breastfeeding mother: she might face problems ‘when milk is too abundant, when it curdles in the breasts, when these become inflamed’, or she might ‘suffer from an abscess or cracks in the nipples’. Such conditions were very painful and genuinely dangerous before antibiotics came along. There were also nutritional considerations: ‘atrophy or wasting may result from long-continued suckling … the bodies of nurses are robbed of nutritive juice … they gradually become thin and reedy’.

However, gentlewomen were in fact much more likely to have enjoyed good, rich and varied diets than the wet nurses they employed, and farming out the task to others came with its own risks. Half-hearted or sleepy nurses had been known to crush or ‘overlie’ their charges during late-night feeds. John Evelyn lost a son this way in 1664: ‘It pleased God to take away my son Richard, now a month old, yet without any sickness … we suspected much the nurse had overlain him.’