If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (28 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

When in 1696 a new tax was levied instead upon windows, the inspectors had only to walk round the outside of the house and count. Initially there was a basic charge of two shillings upon all houses, which doubled to four shillings for houses with between ten and twenty windows. Changes to the banding of window tax helps to explain the mysteriously bricked-up windows in some Georgian city streets. In 1747, the bands were altered so that a house of ten windows or more had to pay sixpence per additional window. Several houses in Elder Street in London’s Spitalfields had one or more openings blocked up at this point so that they would just slip under the ten-window level. (The neat idea that the window tax is the origin of the expression ‘daylight robbery’, though, is regrettably no more than speculation.)

While it was good for government finances, the downside of the window tax was this darkening of people’s homes. ‘A proper ventilation of inhabited houses is absolutely necessary for the public health,’ thundered M. Humberstone in

The Absurdity and Injustice of the Window Tax

(1841). ‘It is like a demon of darkness spreading immorality and wretchedness in its path.’ The idea that a stuffy, unventilated house was unhealthy was further heightened by the continued belief in the concept of miasma.

Another annoying feature of the window tax was the lax and

piecemeal fashion in which it was collected. Mobs sometimes attacked window-tax inspectors who suddenly reappeared after several years’ unexplained absence, and the 1750s saw William Sinclair’s epic and glorious battle with his local window-tax inspector in Dunbeath, Scotland. ‘As to Mr Angus, the Caithness Collector,’ he admitted,

When the rules about window tax were changed, the owner of this house in Spitalfields bricked up several openings to avoid the higher band

I shall honestly tell you the reason I was not civil to him. In the year 1753 he came here and surveyed my windows and reported them to be

28. The next half year he came and surveyed them and found them to be 31 when there was none either added or taken away. In June 1754 he … left a list showing my windows to be 47 and gave that number to the tax man. I appealed and was charged at 31. The last time he came he said there was 34, and I fell into a passion and swore him that I would be revenged.

Because of these difficulties the window tax was eventually repealed in 1851.

In the late seventeenth century, coal began gradually to replace wood as the commonest household fuel. At first it was something of a luxury, as it burned hotter and for longer than wood. But it quickly caught on, and of course caught the government’s eye as something which could be taxed. It seems somehow just that the City of London, destroyed by fire in 1666, was rebuilt partially with the proceeds of the new tax imposed upon coal.

In Georgian towns the ashes created by coal fires would be stored in people’s cellars until the twice-yearly visit of the urban ‘dustman’. In fact, dust and cinders originally formed the main business of the dustman’s life before he branched out into collecting other forms of refuse too. Even today old dustbins might be found marked with the words ‘no hot ashes’.

For your fire to burn successfully, you needed to keep your chimney swept. Until 1855, when they were outlawed and replaced by the ‘humane sweeping’ of chimneys with bendy brushes, nimble chimney boys were sent up the flues. An open fire, though, is a fairly inefficient means of heating because much of the warmth escapes up the chimney. The late-Georgian Count Rumford (he was American, his title awarded by the Bavarian government) transformed home heating when he fitted his revolutionary stoves into fireplaces. Now the fuel could be burned more effectively under better regulated conditions. His motive was fuel efficiency: ‘more fuel is frequently consumed … to boil a tea kettle than with proper management would be sufficient to cook a dinner for fifty men’, he claimed.

However, the eighteenth century’s great innovations in heating took place in hospitals, prisons and cotton mills (where thread was more elastic at higher temperatures). When water-based central heating began to penetrate the domestic sphere, it was more often than not to be found in the greenhouses and kitchen gardens of great estates, where delicate plants and pineapples required hot-water pipes and stoves to be stoked all night by a sleepless gardener. Some of Britain’s earliest domestic hot-water radiators were installed in 1833, and can still be seen at Stratfield Saye House in Hampshire today. But they heated the corridors only: in the abundant aristocratic manner, the living rooms retained the wasteful open fires that were nevertheless so pleasant for their owners. And indeed, why would you bother to install such conveniences in your home if you could afford housemaids to empty the grates before you woke each morning?

A fourteen-year-old housemaid named Harriet has left a heartbreaking letter from the 1870s, describing the heavy work she had to do when the weather turned cold in the autumn:

I have been so driven at work since the fires begun I have had hardly any time for anything for myself. I am up at half past five and six every morning and do not go to bed till nearly twelve at night and I feel so tired sometimes. I am obliged to have a good cry.

At Chatsworth House parties in the 1920s, fifteen fires still burned in the living rooms, each requiring fresh coal four times a day: a total of sixty bucketfuls for the footman to carry.

Yet ‘to the English a room without a fire is like a body without a soul’, observed Hermann Muthesius in 1904.

The many advantages the fireplace is deemed to possess … not least its aesthetic advantages … so completely convince the Englishman of its superiority to all other forms of heating that he never even remotely considers replacing it with the more efficient and more economical stove.

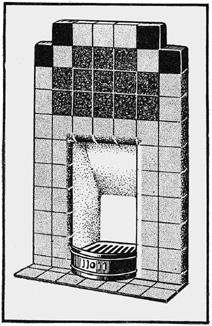

A tile fireplace from the twentieth century. For emotional reasons, the fondness for open flames persisted even after central heating had arrived

In an age of smoke, housemaids had many tricks for cleaning hangings, carpets and furnishings. To freshen a tapestry or hanging, the author of

The Complete Servant

(1830) recommends that you should ‘blow all the dust off with a pair of bellows. Cut a stale loaf into eight pieces. Beginning at the top of the wall, wipe lightly downwards with a piece of the bread.’ Likewise, food could cleanse a carpet: ‘shake well, spread over it with a brush some grated raw potatoes. Brush clean and leave to dry.’ A list of instructions for housemaids made in 1782 recommends strewing tea leaves upon the carpet and then sweeping them up, and also gives an insight into dusting: ‘books are not to be meddled with, but they may be dusted as far as a wing of a goose will go’. These cleaning tasks were endless in Victorian London, where people even thought it worth thrusting a cloth into their front-door keyholes to help prevent the dirty air of a poisoned city from seeping into their homes.

Living rooms got even dirtier when oil lamps began to replace candles in the later eighteenth century. ‘I have seen houses almost filled with the smoke from lamps, and the stench of the oil,’ a footman recollected. In a large establishment lamps required a separate new room for the cleaning of their glass shades. The Duke of Rutland, at his home, Belvoir Castle, had a trifling 400 lamps for his hard-working servants to polish. They hated it. ‘Lamps were often neglected,’ reveals

The Footman’s Directory

of 1825, ‘especially in households where servants changed jobs quickly, since everyone thought they would last their time.’

But the oil lamp would soon be superseded by gas, which had long been exploited by human beings, and possibly provided the source of the perpetual flames in Greek and Roman temples. It made its appearance in modern Britain in factories, asylums and theatres long before it penetrated the home. This was coal gas, produced by baking coal. Today our gas is natural, piped from pockets beneath the sea, and it burns much more brightly than the coal gas used between late Georgian times and the 1970s.

William Murdoch, a Scottish engineer working in the Cornish mining industry, was the greatest innovator in the field of gas lighting, employing it in 1792 to illuminate his offices in Redruth. His name is less well known, though, than Frederick Windsor’s, the man who organised a public demonstration of this new lighting for George III’s birthday in 1807, and who set up the first public gas-supply company. A showman by nature, Windsor was a great proselytiser for his new product, which was mysterious and rather frightening. People marvelled at the properties of this ‘illuminated air’, but remained fearful of explosions and fires. Windsor (somewhat unconvincingly) reassured potential clients that coal gas was even ‘more congenial to our lungs than vital air’.

In 1812, the Gas Light and Coke Company set up the first

gasworks in Britain. Gas was piped across towns by plumbers, the people whose skills seemed best suited to this new task, so its vocabulary is identical to that of water: ‘mains’, ‘taps’, ‘flow’, ‘pressure’ and ‘current’. At first gas was mainly used for street rather than domestic lighting. Westminster Bridge was illuminated by gas as early as 1813, and there would ultimately be more than 60,000 gas street lamps all over London. One thousand six hundred still remain today, in Westminster and around St James’s and Buckingham Palaces. They are maintained by six gas-lamp attendants employed by British Gas, a remnant of the once vast pool of lighters who went round cities at dusk with their long torches.

I’ve had the pleasure of using one of these torches in the company of Phil Banner, who’s spent forty-two years with British Gas. He showed me how his works: you squeeze a rubber bulb at one end, which forces a gust of air upwards, and the flame burning at the other end leaps out like a dragon’s tongue and ignites the gas. (The remaining lamps are usually lit today by a clockwork timer rather than a torch.) Lighters like Phil were once familiar figures on the London streets. Prostitutes might pay them

not

to light the lamps in corners convenient for their business, and those needing to rise early might ask the lighter to knock on their doors during the dawn round when the lamps were extinguished.

By the 1840s, supplies were working well enough for gas to make a tentative appearance in the urban home. From this point on, any British town with more than 2,500 inhabitants usually had a gasworks, and gas lighting became a must-have in middle-class living rooms. One writer in the

Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine

even recommended that parties ‘must always be given by gas light … if it be daylight outside, you must close the shutters and draw the curtains’, the better to show off your gasoliers.

But the inexpensive and slightly lowbrow connotations of gas

meant that it was still shunned by the upper classes: they stayed loyal to candles. At the same time, billing remained a quarterly affair, placing it out of the reach of the truly poor. It was only in the 1890s that the gas companies, worried about losing business to their new rivals selling electricity, introduced the ‘penny in the slot’ meter. One Victorian cartoon shows a desperate father trying to commit suicide by sticking his head in the gas oven. His concerned family beg him to put off the deed until the cheaper evening gas rate starts.

Gas must have provided a quite stunning improvement in light levels and, therefore, in people’s ability to entertain themselves in the evenings. It nevertheless had many drawbacks. There were frequent explosions and fires; it was not uncommon for gas leaks to be investigated by the light of a match. Also, gas consumed the oxygen in a room’s air, replacing it with black and noxious deposits. The aspidistra became such a popular plant because it was one of the few that survived in oxygen-starved conditions. The reason that Victorian ladies have such a reputation for fainting is partly because of tight lacing, but also because of the shortage of oxygen in gas-lit drawing rooms. In 1904, Hermann Muthesius still noticed ‘a widespread dislike of gas-lighting’, and its confinement to ‘halls and domestic offices for fear of the dirt caused by soot and the recognition of the danger to health that arises from piping gas into the room’. (Clearly the health of the servants working in the domestic offices was a lesser concern for homeowners.)