If These Walls Had Ears (34 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

One day when they were out in the yard, looking at the house, a young black man stopped by. He painted houses, he said, and

he would love to paint theirs. He told Jack he’d painted houses all over Hillcrest. “If you’ll take me in your car, I’ll show

you,” the man said. So Jack did. They drove all around the area. “If you’ll stop,” the man said, “we’ll go up to the door

and talk to the people.” But Jack felt funny about things like that. He said he would take the man’s word.

Jack had to provide the ladders, the air compressors, and gas money so the painter could get to the job. Jack felt like a

cash machine. Sometimes he would give the man money, and then the man wouldn’t show up for days. Donna was on Jack to get

the job done. They limped along like that until the man had done all but one side and the chimney.

Then the painter pushed Jack over the brink. “He came to my office one day and he needed money,” Jack recalls. “We had a screaming

thing, and I gave him money arid told him, ‘This is what I think I owe you for what you’ve done. Now go, begone, I don’t ever

want to see or hear from you again.’”

“Oh no, sir,” the painter said, “I’m going to finish the job.”

“No you’re not,” Jack said. “You’re

through.

“ Jack went home and told Donna he had fired the painter.

So they had to finish the job together. As fate would have it, Jack was afraid of heights, so he stood in the yard, working

the compres sor, while Donna got up on the ladder and painted the house—all but the chimney, which was still unpainted when

I bought the place.

Jack didn’t know the coda to that story, but I told him. For at least our first year in this house, I would occasionally be

interrupted in my office by a knock on the door. I used the downstairs front room then. I would go to the door and a young

black man would be standing there. I could see behind him that another person was waiting in a car. The young man would introduce

himself as tile one who had painted this house. He’d brought someone over to see it, and would I mind?

I figured I shouldn’t if

he

didn’t. Once, I heard him and his potential client standing just outside my office window discussing the quality of the job.

The other man was older, and he didn’t look pleased. His brow was furrowed and his lips were tight. He pointed to a section

of alligatored woodwork that obviously hadn’t even been sanded before the new gray paint was brushed on.

“I would want a better job than that,” the man said.

Toward the end, Jack began to sense that he was a dinosaur. After selling his own business and doing nothing for a while,

he’d bought another company that was similar. It had been owned by a friend of his. One morning, the man had gone out to get

in his car to leave on a business trip and his estranged wife walked up and shot him in the head. Killed him. Since Jack was

available, he was asked to manage that company for a time. Eventually, he bought it.

And business remained good until about a year after he and Donna moved from this house, at the end of the eighties. But even

before they left, Jack saw the writing on the wall. “Sam’s and Wal-Mart took care of that business,” he says. “There are no

wholesale distributors anymore. Everybody’s direct.”

The time-sharing business was feeling shaky, too. Combine that with the fact that Andi had graduated from high school in 1988,

and it was enough of a sea change to make them want to get out from under this old house.

And so they painted. And on a bright Sunday morning in late August of 1989, I walked through this house, marveling at the

TV sets and the couches and the padded walls and the relentless shades of

green.

Then, outside the kitchen door, I spied a coffee cup, still steaming, and it bore a fresh red lip print that made my heart

leap into my throat.

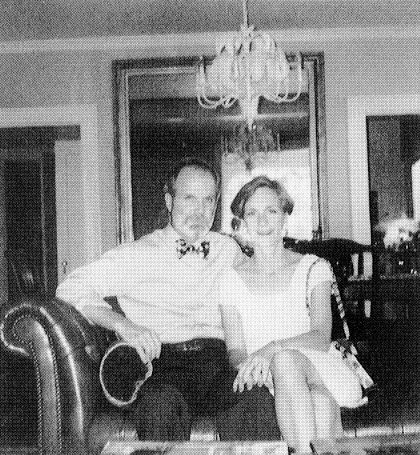

Jim and Beth Morgan in the living room, 1991. The mirror in the background hangs in the spot where Jessie Armour had her Empire

sideboard decades before

.

Morgan

1989

1992

I

have a thing about light. My sensitivity to it isn’t physical; it’s emotional— visceral, even. Our next-door neighbors sit

in their living room or their den with the overhead light on. As much as I like and enjoy being with John and Linda, I can’t

understand how anybody can do something like that. It’s not a subject I would ask them about—you either have a thing about

light or you don’t.

The first thing I do every morning is turn on the fluorescent light over the sink. Beth would leave it off all day and be

perfectly happy. But if I go into the kitchen and that light isn’t on, I feel a nagging worry, like one of those vague concerns

that floats across your mind just when you’re sitting down to enjoy yourself, as at a movie. So I turn that light on and leave

it on all day. The next thing I do is switch on the small lamp behind the coffeepot, creating shadow figures in that otherwise-dark

corner.

On the other hand, when we sit on the porch at night, I have to have the floor lamp inside the living room window turned off.

I like the porch best when it’s dark—so dark that all you see is the occasional glow of a cigarette lighting up like a red

firefly, then fading back into the unseen sounds of tinkling ice cubes and creaking rockers.

In my house, I know the times of day that produce the light I like best. The Geranium Room takes on a rosy glow at precisely

8:30 on spring mornings. I’m seldom in that room at that hour, but the effect is more pronounced from the hall, anyway. As

busy as our mornings are, I usually make a point of stopping for a moment to stare in wonder at the light bouncing off the

walls and blending with the east sun. The result is a pink mist thick enough to disappear into.

The kitchen is warmest at 11:30 in the morning, when the sun finds the windows and cuts across the pine table like a Hopper

painting. My office catches an intriguing sliver of west sun late in the day, after 4:00 RM. It beams in through the French

doors and warms the wall over my oil paints, turning it golden.

I also know the time of day whose light I like least. I adjust the living room miniblinds slightly upward at 6:30 on summer

evenings, especially if we’re having someone over. Otherwise, the sun’s rays will spray the floor and wall and dining room

mirror, ricocheting through the room like a drive-by shooting. Such an onslaught inevitably exposes a thin film of dust no

matter how often we vacuum—on the hardwood floors between the dining room and hall.

Since I’ve been writing this book, I’ve become especially conscious of my feelings about light. I like rooms moody, indirect.

I like candles on the dinner table. I don’t like track lights, though we have a vestigial row of the things left on our living

room ceiling, a legacy of the Burneys. I don’t know what I was thinking.

Mainly, I don’t like a spotlight on me. Now it occurs that I should’ve thought of that before I started writing this book.

When I began, I had no idea how much my illuminating the secrets of my house might also require spotlighting secrets of my

own. If our houses are us, then we are our houses. Now I find I’m obliged—by the saga of which I’m a part—to reveal glimpses

of my own faulty wiring, cracks in my own foundation.

It’s easier just to shut the blinds.

But I began this story as a search, and much of that search had to do with me. I suppose I’ll survive the glare. We’re all

houses. We all have our histories and secrets, our losses, our damaged hearts. No wonder we don’t like looking into the black

broken places inside our closets. No wonder we cringe at the thought of crawl spaces, or feel a chill about dank basements

or skeletal attics. We go through our lives not knowing those we love, the places we live in, or even ourselves. We stand,

separately, row after row of us on street after street all over the world—all houses. But in spite of ourselves, we yearn

to be homes.

Beth and I came to 501 holly packing separate pasts, looking for a house understanding enough to accommodate those and our

uncertain future, too.

For me, the handful of days that led up to Holly Street were

the

pivotal moments in my life to that point, both personally and professionally. By that I mean, I actually made a conscious

decision on both fronts. I know how ridiculous that sounds. I also know that well-adjusted, mature people who don’t confuse

themselves with a rich inner life probably won’t understand. But since I’d always lived most satisfyingly inside my head,

I’d made conscious decisions only about my work. The personal side, in a way, had just come along for the ride. I’d allowed

decisions to be made for me, or allowed time to take its course. This includes the subject of marriage, which goes a long

way toward explaining why I now have two ex-wives.

At the end of August 1989, after our magazine had been sold and our staff replaced, I turned down an offer for the top job

at a big-city magazine—consciously deciding to step off base as a day-to-day, salary-drawing magazine editor and instead to

accept a part-time consulting deal so I could write. I called an old boss of mine, and he told me, “The only risks I’ve ever

regretted were the ones I didn’t take.” The ramifications were frightening but exhilarating. They became even more adrenaline-producing

when you added my decision, one day later, to ask Beth to marry me. My plan was for us to stay in Arkansas and write, to live

together and work at home. She accepted, and the next morning I called my Realtor to look for a house.

I believe Beth made a measured decision, too. She’s endured much pain in her life. Her father was killed when she was fifteen,

and in many ways her family splintered after that. Right after college, she married her first husband—one of a brood of ten

children—trying to find a family to fit into. A home. She learned, of course, that home isn’t a quantitative thing. just before

she and I met, she’d been told that her beloved brother and ally Brent, an interior decorator in New York, had been diagnosed

with HIV. That had been the most devastating blow of all.

I first saw her in 1986, at a meeting for the new magazine we were starting in Little Rock. A writer, she had come to hear

some of us talk about staffing and other subjects. I spotted her in the crowd. She looked like someone who had peered into

the black broken places. As I watched her that day, I thought of a

New Yorker

cartoon that had always amused me about my own well-known moodiness. I’d kept it pinned to my office wall for the longest

time; then I moved again, of course, and lost it. It showed a man and woman at one of those trendy Manhattan parties. In the

background, you could see that the apartment was abuzz with smart talk. In the foreground, however, a young man sat alone

on the terrace. A woman had just approached him. “You’re not having much fun, are you?” she said. “I like that in a man.”

Beth didn’t seem to be having much fun.

I was right about her and I was wrong. Wrong, in that she has a relentless spirit, an irrepressible

fun

about her that won’t be quashed. This is the woman who introduced me to martinis. But I was right about her, too. It would

be a long time before she and I married, but the sadness I saw in her that day would color our first three years on Holly

Street.

* * *

Like the Burneys, we moved in three weeks before our wedding. We asked for and received special dispensation from Beth’s ex

to let his young daughters sleep under the same roof with a man and woman who were living in sin.

Blair was eight, Bret five when we came to Holly Street. I remember the day we brought the girls over to see the house for

the first time. We’d decided that Bret would have the smaller room at the top of the stairs, and Blair the larger bedroom

adjoining. Both girls were aghast when they saw the fabric walls in Blair’s room and the two baths. I told the girls that’s

how I had known this was the perfect house for our crazy new family—the place came complete with padded walls.

I decided that if Beth and I didn’t call off the wedding in those first few weeks, we would have no problem lasting forever.

We’d tried to get the painters scheduled before we moved in, but the Burneys were already being pressed. Looking over my house

file six years later, I almost get sick summoning back that frantic time. I’ve never enjoyed the business of buying a house.

I don’t know how you buy a place in which you’re going to live without wanting it so much that you might as well not even

negotiate. Many—most—houses don’t speak to me with any poetry whatsoever, and so the ones that do are almost too special.

Then there’s the eternal question of whether I’ll be able to afford it once I’m in. No matter how many times I go through

this damnable dance, there are always nights when I lie in bed in the dark, staring toward the ceiling, turning numbers over

in my head. Suddenly, I’ll remember two thousand dollars I had forgotten, and I’ll either rise in a cold sweat or I’ll doze

off to sleep—depending in whose favor my addled brain had temporarily failed.