If Britain Had Fallen (36 page)

The life of a slave-worker was but one step removed from the hell of incarceration in a concentration camp. Many of those who experienced it died, but one who survived, though with his health ruined, is a Frenchman taken against his will from the Unoccupied Zone of France and sent to work in Jersey. This was his life—as it might have been the life of millions of British citizens, had the Germans carried out their deportation plans. The working day lasted from 6 am to 6 pm, or, in winter from 7 to 7 or 8 to 8, with one half-day off every fortnight, but this was as much to be dreaded as looked forward to for on that day there was no food after midday, the Germans explaining simply, ‘Nichts Arbeit, nichts Essen’—’No work, no food’. The food consisted of ‘cabbage soup without cabbage’ and some coarse bread. The men tried to slake their appetite on potato peelings stolen from the dustbins, on bread thrown out by their German guards as uneatable, and on raw limpets, torn from the rocks, which the local people also collected, though to feed their pets.

Hunger becomes an attitude of mind … . You think about food, you hear about food, you wake up in the mornings thinking about food, you talk about food, all you can think about and talk about is food, food all the time. And when you cannot fill up that gap in your stomach you become a zombie.

They were not paid, received no luxuries or comforts of any kind and very few clothes and this man was conscious all the time of the deliberately brutalising effect of the regime imposed upon them. ‘You become like an animal, you fight for everything, you fight for a place in the queue

at night to get your soup … you fight to get a bunk … to sleep by the fire. Before you used to be compassionate … . Today you become hardened.’ Many of his workmates died of malnutrition and ill-treatment—those who survived have since been crippled with rheumatism and other complaints—but worst-treated of all were the Russians, whom the Germans regarded as barely human. He personally saw one Russian murdered by a German guard who ‘hit him with a shovel and practically cut him in half.

No Channel Islanders were sent as slave labourers, but many were deported. The first warning came on Tuesday 15 September 1942, two years after the arrival of the Germans, and it was a clear breach of the promise then given that ‘in the event of peaceful surrender the lives, property and liberty of peaceful inhabitants are guaranteed’. The German authorities on the islands were not, however, to blame. Lord Coutanche has since described how with the Attorney-General he called on the German Field Commandant, then installed in the boarding house of the chief island boys’ school, Victoria College, and ‘we protested as hard as we could protest’ until the colonel concerned picked up a paper from his desk and said ‘ “That document, that order for the deportation of these people, is signed by the Führer himself and you’ve worked with us long enough here to realise that there is nobody on earth who can stop that order being carried out.” ‘

The decision, which seems to have been due to Hitler’s obsession that the allies planned to recapture the Channel Islands as a base for the invasion of Europe, was that anyone whose normal home was not on the Channel Islands, such as those caught there on the outbreak of war, and all men aged sixteen to seventy born outside the islands, with their families if they were married, would be ‘evacuated and transferred to Germany’. The Germans planned, in their tidy way, to deport 2000 from Jersey and Guernsey together, but in the event they carried off about 1100 from the former and 890, later raised to 1000, from the latter, a total of 2100. It took them little time to decide who should go, for they had already compiled a nominal roll of all the islands’ inhabitants, showing their place of birth, which became the vital test applied. Some absurd anomalies occurred as a result. Lord Coutanche personally drew attention to one, of a man marked down for deportation as English merely because his mother had gone home to her mother in England to have her baby before rejoining her Jersey-born husband in his native island. ‘I went up and I explained what a fine chap he was, World War soldier and all that sort of thing. There was nothing to be done: “There he is on the list and there he stops”, although that man was as much a Jerseyman as I am.’ The present Town Clerk of St Helier also witnessed an example of German inflexibility, mingled with callousness, during the deportation of the second batch of local people: ‘One man’, he remembers, ‘had a heart attack. There was some German officer just stood over him and photographed him while he was lying on the ground.’ The unfortunate sufferer was eventually carried on to the boat, escorted by a nurse.

Behind the scenes this official, and other Jersey residents, were doing all they could to protect their fellow citizens. ‘We had to go up to the commandatura at College House’, he remembers, and ‘go through the list with the Germans, and if there was any particular reason why a person or family should not be deported we had to give them those reasons. We did this reasonably successfully … so much so in one case they said, “Well, if we can’t send all these fellows, we’ll have to send you.” ‘ In fact very few ‘substitutions’ by volunteers willing to take the place of those too weak to go were allowed. One elderly man killed himself rather than leave his home and a few girls born on the mainland escaped deportation by rapidly marrying native-born Jerseymen. One man then running a canning factory managed to save some of his employees by persuading the Germans that they were engaged on essential work and could not be spared, but ‘the second time I went down there it wasn’t quite so easy’, though he managed eventually to get both the threatened men struck off the list. ‘One I said was consumptive … and he was sent out straight away, he and his wife and a little baby, and the other fellow I said was our main agricultural engineer though he was just a labourer. I said that our work would stop if he was taken … and they let him off.’

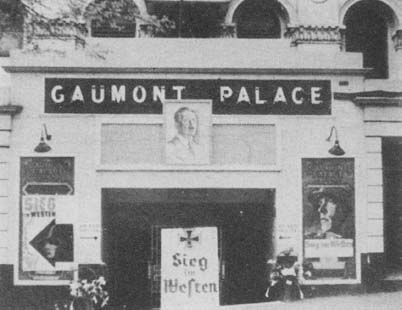

On Guernsey, after a wretched weekend spent in packing, the unfortunates finally selected were assembled at the Gaumont cinema where, in happier times, they had queued for an evening’s entertainment. Now, as the sad lines of elderly couples, young families, women with babies in their arms or with frightened children clustered round them, shuffled forward, they were checked in not by a commissionaire but, one watching journalist noted, by a ‘superior-looking, fat-gutted Nazi overseer’. This unsympathetic individual acted as the final court of appeal, for some young people not on the list ‘when a particularly aged or infirm couple came forward to be checked in … stepped quietly forward to say to the Germans “Can we go instead of this old couple?”’. ‘It was a good job’, admits one Jersey woman, looking back on her day-long wait with her two small children at the weighbridge near the former railway station at St Helier where they were assembled, ‘that we didn’t know before we left about those horror camps … otherwise I think we’d have just died of fright then.’

30

German troops on Guernsey

31

Occupation Orders, July 1940. (The first issue of the Guernsey

Star

ever supplied free)

32

German troops in St Peter Port, Guernsey

33

German tanks on occupied Guernsey

34

A German military band in the Royal Parade, St Helier

35

A Guernsey cinema taken over by the Germans (the film on show is

Victory in the West;