Ida a Novel (4 page)

Authors: Logan Esdale,Gertrude Stein

More shipments followed until war suspended the project in 1940. (It resumed in 1946.) By 1938 Stein’s sorting through her manuscripts was having its effect as

Ida

began to take on a composite identity. More intertexts would be added in 1939 and 1940. In addition, one of the passages she added to

Ida

in the final months of composition speaks to her construction of the novel as an analogue to her archive, with intertexts from the start of her writing life (“Hortense Sänger”) to its most recent moments (“My Life With Dogs”): “Sometimes in a public park [Ida] saw an old woman making over an old brown dress that is pieces of it to make herself another dress. She had it all on all she owned in the way of clothes and she was very busy.” We can read the old woman as Stein and the public park as the Yale Library. The old dress represents the early

Ida

manuscripts and even her career’s work as a whole (she “had it all on”); the new dress is what she will send to her publisher. With this sewing metaphor in mind, this edition of

Ida

not only draws attention to the seams in the dress-novel but gives a selection of those other “pieces,” so that we can follow the cut of her scissors and path of her needle.

Stein designed

Ida

to be composite to draw attention to the continuity of her writing career and the contingent relation of one text with others. Dydo has said about Stein’s writing in general that one “piece engenders the next, so that each becomes a context for the next. Her life’s work is not only a series of discrete pieces but also a single continuous work” (

LR

78). This is manifestly true for

Ida

, and in that way the novel was designed as an advertisement to readers, exhorting them to read more of what Stein had written in the mid- to late 1930s and earlier too. Even though

Doctor Faustus Lights The Lights

and

To Do: A Book Of Alphabets And Birthdays

were not published in Stein’s lifetime, she could reassure herself that eventually we would read

Ida

in its historical context, and the “continuous work” quality would be recognized. Again, from 1937 until she died, she knew that any writing she saved (drafts included) would have a public home at Yale. The archive came as a tremendous relief because for many years she had been anxious about her unpublished writing, and now all of it would survive and be seen.

To this point I have connected how Stein wrote

Ida

with her archive and the need to affirm her identity as a writer (not just a personality).

21

This need arose three years before the archive’s inception, however, when

The Autobiography Of Alice B. Toklas

brought her the fame she had long hoped would be hers. Two texts written in the wake of that event, early in 1934, anticipate the textual identity and composition of

Ida

: “And Now,” which Stein published in the September 1934 issue of

Vanity Fair

, and “George Washington,” the final text in

Four In America

(1933–1934).

As Stein reflected on her new celebrity in “And Now,” she thought of Paul Cézanne’s belated success: “I remember when [Cézanne received] his really first serious public recognition, they told the story that he was so moved he said he would now have to paint more carefully than ever. And then he painted those last pictures of his that were more than ever covered over painted and painted over” (

HWW

64). Then she offers a comparison that again reaches back to the early twentieth century: “I write the way I used to write in

The Making Of Americans

[1903–1911], I wander around. I come home and I write, I write in one copy-book and I copy what I write into another copy-book and I write and I write” (

HWW

66). So as both a younger and older writer, Stein had to write and reread and unwrite her way into a state of unself-consciousness, where she felt relatively free of audience expectation. This comment on recursive method is from 1934, but it exactly describes the

Ida

manuscripts: for three years (1937–1940) Stein moved from one copybook or draft sequence to another.

Alongside “And Now” and “The Superstitions Of Fred Anneday, Annday, Anday A Novel Of Real Life” (included here), Stein was finishing

Four In America

, with its chapters on four quintessential American men: Ulysses Grant, Wilbur Wright, Henry James, and George Washington. When

Four In America

was published in 1947, it contained a note alerting readers that the first part of “George Washington” had previously been published, in a 1932 issue of

Hound and Horn

. It was not recognized until Dydo’s 2003 book

Gertrude Stein: The Language That Rises, 1923–1934

, however, that other preexisting texts had been used, which makes

Four In America

a precedent for

Ida

. “The amazing number of piecemeal inclusions from many sources,” Dydo writes, “along with hesitations about uncertain progress, suggest how Stein cut and pasted the Washington section together” (

LR

593). Further critical discoveries of this kind may come to light. All of the moving among notebooks, as well as working concurrently on different pieces, blurred the line between texts and encouraged cross-fertilization.

After the American lecture tour (1934–1935), Stein wrote

The Geographical History Of America

, which introduced an important binary in her aesthetic lexicon: human nature (or identity) and human mind (or entity). “Events are connected with human nature,” she says, “but they are not connected with the human mind and therefore all the writing that has to do with events has to be written over, but the writing that has to do with writing does not have to be written again, again is in this sense the same as over.”

22

The term “human mind” is in part a spiritual directive, a challenge to imagine existing without identity. As Wilder understood human mind, it happened when one could “realize a non-self situation,” when the creative self was experienced without external recognition. Just as a true believer does not remember God as if God had an identity but instead experiences God, Stein’s human mind was experienced in the mystery of living and writing. Events, like linear time and relational identity, usually prohibit “non-self situations,” and events are the meat of narrative—conflict, character development, closure. Stein limits those typical events in

Ida

, but marriages and moves do happen, and in consequence, “writing that has to do with events has to be written over,” into abstraction.

As Stein went from draft to draft of

Ida

, she thus generated a textual world to work within. She used her writing to make more writing. She sewed a “dress” and then cut it apart and sewed again. Besides copying from one notebook to another, she also used preexisting texts unmotivated by the current occasion, texts written prior to her fame. To reach human mind for

Ida

, she put into action both the writing-over method described in “And Now” and the cut-and-paste method used in

Four In America

. Stein would refer to the former in a 1941 letter to Carl Van Vechten: “Ida you know was done over and over again, before it finally became what it is” (see “Selected Letters”). These methods have only slowly been recognized in Stein scholarship, and this edition of

Ida

puts both on display.

I conclude with three examples that show incorporation and radical rearrangement. (See the genealogy of the novel for a complete description of the writing process.) The first two are from typescript copies of the second version of

Ida

, which Stein wrote by hand on loose sheets in 1938–1939 and titled “Arthur And Jenny.” (The Jenny character was named Ida in the 1937–1938 version of the novel, and later in 1939 Stein changed Jenny back to Ida.) In 1938 Stein wrote an episode for Jenny that vaguely alluded to “Hortense Sänger”:

[Jenny] did want to go to a meeting whenever there was one.

One day she went to one, a great many were crowded together and she was crowded with them and then well she was more crowded than any of them. Did she stop it. She did not. Her name was Jenny and she did not stop it stop being more crowded than any of them there inside that building. Later she wondered about it. Could she have stopped being more crowded than any of them there in that building and did she like it. (YCAL 26.534)

Then in 1939, after writing another 250 sheets of “Arthur And Jenny,” Stein had Toklas produce the typescript we see here, on which she added a handwritten note: “The story of the church and her relatives” (

Figure 1

). The note indicates her decision to expand the episode and reposition it. Indeed, the version we see in

Ida

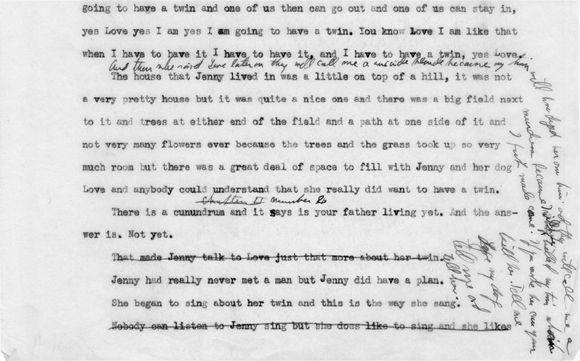

is over four times longer and offers more detail on Ida’s erotic indiscretion in a church in front of some relatives. The second example is another handwritten note on a 1939 typescript, an addition that Stein copied from a text she had recently written,

Lucretia Borgia A Play

(

Figure 2

).

The third example involves a sequence of fourteen paragraphs in

Ida

(see 28) that Stein cut and pasted from five locations in “Arthur And Jenny,” covering eighty pages and two separate draft sequences (YCAL 26.534, pp. 78–85, 101–106, 143–146, 158; YCAL 26.536, pp. 22–23). Using “Arthur And Jenny” as raw material, Stein wrote these paragraphs for the final

Ida

version in winter 1939–1940, at which time she added two completely new paragraphs.

23

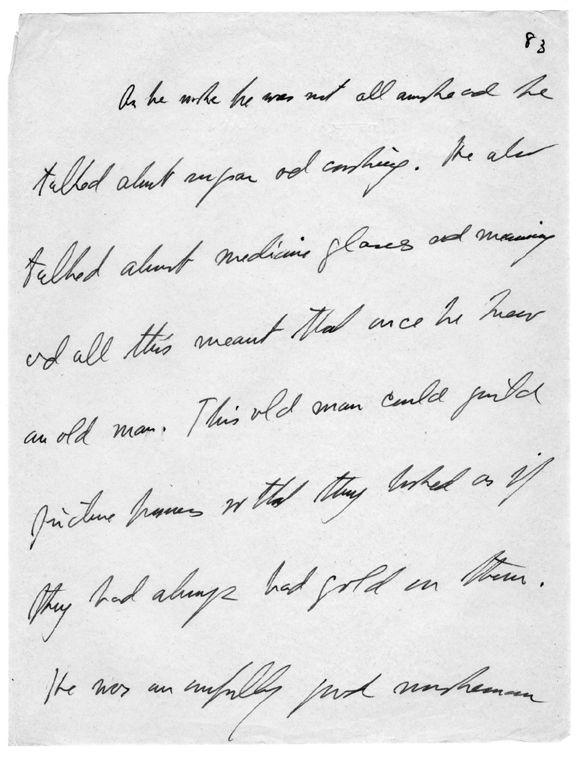

She started the rewriting process by copying from pages 78–85, which begin, “He [Arthur] tried several ways of going and finally he went away on a boat and was shipwrecked and had his ear frozen.” Page 83 in that section illustrates the remarkable complexity of this cut-and-paste process (

Figure 3

).

Figure 1: “The story of the church and her relatives” (YCAL 27.541).

Figure 2: “And then she said Love later on they will call me a suicide blonde because my twin will have dyed her hair and they will call me a murderess because I will have killed my twin which I first made come. If you make her can you kill her. Tell me Love my dog tell me and tell her” (YCAL 27.540).

Stein retained, in modified form (see the paragraph that begins “It was a nice time then”), only the first sentence and a half from this page (“As he woke he was not all awake and he talked about sugar and cooking. He also talked about medicine glasses”). She dropped some altogether (“and meaning and all of this meant that once he knew an old man”) and used the rest many paragraphs further on (“This old man could gild picture frames so that they looked as if they had always had gold on them. He was an awfully good workman”). After “medicine glasses” in

Ida

is a paragraph that begins “Arthur never fished in a river,” which came from pages 101–106. “Arthur often wished on a star” and the following three paragraphs came from pages 143–146, and the paragraph with “they managed to make their feet keep step” came from page 158. The paragraph in

Ida

that begins “Well anyway he went back” came from pages 22–23 in another manuscript sequence: