Ida a Novel (36 page)

Authors: Logan Esdale,Gertrude Stein

She left the University and, settling in Paris, applied herself to the problem. The result was a novel of one thousand pages,

The Making Of Americans

, which is at once an account of a large family from the time of the grandparents’ coming to this country from Europe, and a description of “everyone who is, or has been, or will be.” She then went on to tell in “A Long Gay Book” of all possible relations of two persons.

This book, however, broke down soon after it began. Miss Stein had been invaded by another compelling problem: How, in our time, do you describe anything? In the previous centuries writers had managed pretty well by assembling a number of adjectives and adjectival clauses side by side; the reader “obeyed” by furnishing images and concepts in his mind and the resultant “thing” in the reader’s mind corresponded fairly well with that in the writer’s. Miss Stein felt that that process did not work any more. Her painter friends were showing clearly that the corresponding method of “description” had broken down in painting, and she was sure that it had broken down in writing.

In the first place, words were no longer precise, they were full of extraneous matter. They were full of “remembering,” and describing a thing in front of us, an “objective thing,” is no time for remembering. Miss Stein felt that writing must accomplish a revolution whereby it could report things as they were in themselves before our minds had appropriated them and robbed them of their objectivity “in pure existing.”

Those who had the opportunity of seeing Miss Stein in the daily life of her home will never forget her practice of meditating. She set aside a certain part of every day for it. In Bilignin, her summer home in the south of France, she would sit in her rocking chair facing the valley she has described so often, holding one or the other of her dogs on her lap. Following the practice of a lifetime she would rigorously pursue some subject in thought, taking it up where she had left it on the previous day. Her conversation would reveal the current preoccupation: It would be the nature of “money” or “masterpieces” or “superstition” or “the Republican Party.”

She had always been an omnivorous reader. As a small girl she had sat for days at a time in a window seat in the Marine Institute Library in San Francisco, an endowed institution with few visitors, reading all Elizabethan literature, including its prose, reading all [Jonathan] Swift, [Edmund] Burke, and [Daniel] Defoe. Later in life her reading remained as wide but was strangely nonselective. She read whatever books came her way. (“I have a great deal of inertia. I need things from outside to start me off.”) The Church of England at Aix-les-Bains sold its Sunday School library, the accumulation of seventy years, at a few francs for every ten volumes. They included some thirty minor English novels of the ’70s, the stately lives of Colonial governors, the lives of missionaries. She read them all. Any written thing had become sheer phenomenon; for the purposes of her reflections absence of quality was as instructive as quality. Quality was sufficiently supplied by Shakespeare, whose works lay often at her hand. If there was any subject which drew her from her inertia and led her actually to seek out works, it was American history and particularly books about the Civil War.

And always with her great relish for human beings she was listening to people. She was listening with genial absorption to the matters in which they were involved. “Everybody’s life is full of stories; your life is full of stories; my life is full of stories. They are very occupying, but they are not really interesting. What is interesting is the way everyone tells their stories”; and at the same time she was listening to the tellers’ revelation of their “basic nature.” “If you listen, really listen, you will hear people repeating themselves. You will hear their pleading nature or their attacking nature or their asserting nature. People who say that I repeat too much do not really listen; they cannot hear that every moment of life is full of repeating.”

It can be easily understood that the questions she was asking concerning personality and the nature of language and concerning “how you tell a thing” would inevitably lead to the formulation of a metaphysics. In fact, I think it can be said that the fundamental occupation of Miss Stein’s life was not the work of art but the shaping of a theory of knowledge, a theory of time, and a theory of the passions. These theories finally converged on the master question: What are the various ways that creativity works in everyone?

Miss Stein held a doctrine which informs her theory of creativity, which plays a large part in her demonstration of what an American is, and which helps to explain some of the great difficulty we feel in reading her work. It is the Doctrine of Audience. From consciousness of audience, she felt, come all the evils of thinking, writing, and creating.

In

The Geographical History Of America

she illustrates the idea by distinguishing between our human nature and our human mind. Our human nature is a serpents’ nest, all directed to audience; from it proceed self-justification, jealousy, propaganda, individualism, moralizing, and edification. How comforting it is, and how ignobly pleased we are, when we see it expressed in literature. The human mind, however, gazes at experience, and without deflection by the insidious pressures from human nature, tells what it sees and knows. Its subject matter is indeed human nature; to cite two of Miss Stein’s favorites,

Hamlet

and

Pride and Prejudice

are about human nature, but not of it. The survival of masterpieces, and there are very few of them, is due to our astonishment that certain minds can occasionally repeat life without adulterating the report with the gratifying movements of their own self-assertion, their private quarrel with what it has been to be a human being.

Miss Stein pushed to its furthest extreme the position that, at the moment of writing, one should rigorously exclude from the mind all thought of praise and blame, of persuasion or conciliation. In the early days she used to say: “I write for myself and strangers.” Then she eliminated the strangers; then she had a great deal of trouble with the idea that one is an audience to oneself, which she solves in her posthumous book,

Four In America

, with the far-reaching concept: “I am not I when I see.”

It has often seemed to me that Miss Stein was engaged in a series of spiritual exercises whose aim was to eliminate during the hours of writing all those whispers into the ear from the outside and inside world where audience dwells. She knew that she was the object of derision to many and to some extent the knowledge fortified her. Some of the devices that most exasperate readers are at bottom merely attempts to nip in the bud by a drastic intrusion of apparent incoherence any ambition she may have felt within herself to woo for acceptance as a “respectable” philosopher. Yet it is very moving to learn that on one occasion when a friend asked what a writer most wanted, she replied, throwing up her hands and laughing, “Oh, praise, praise, praise!”

Miss Stein’s writing is the record of her thoughts, from the beginning, as she “closes in” on them. It is

being written

before our eyes; she does not, as other writers do, suppress and erase the hesitations, the recapitulations, the connectives, in order to give you the completed fine result of her meditations. She gives us the process. From time to time we hear her groping towards the next idea; we hear her cry of joy when she has found it; sometimes, it seems to me that we hear her reiterating the already achieved idea and, as it were, pumping it in order to force out the next development that lies hidden within it. We hear her talking to herself about the book that is growing and glowing (to borrow her often irritating habit of rhyming) within her.

Many readers will not like this, but at least it is evidence that she is ensuring the purity of her indifference as to whether her readers will like it or not. It is as though she were afraid that if she weeded out all gropings, shapings, re-assemblings, if she gave us only the completed thoughts, the truth would have slipped away like water through a sieve because such a final marshalling of her thoughts would have been directed towards audience. Her description of existence would be, like so many hundreds of thousands of descriptions of existence, like most literature—dead.

’47: The Magazine of the Year

1.8 (Oct. 1947): 10–15

Reviews of

Ida A Novel

in 1941

In one of Stein’s lectures, “Portraits And Repetition,” she noted the irony of the response her work had gotten in the popular press: “[E]very time one of the hundreds of times a newspaper man makes fun of my writing and of my repetition he always has the same theme” (

LIA

167). The reviews gathered here put that irony—one review repeating another—on display. One after the other, they describe the novel as obscure, and cut short their analysis of the novel to reference Bennett Cerf’s address to the reader (

Figure 15

). Of course there are deviations: the Hauser, Rogers,

Time

, and Roscher reviews are sincere and insightful, while those by O. O. and Auden mimic her style, and Littell and Mann, in the face of a novel with little plot, invent their own stories in response.

The useful criticism in these reviews is partly what makes them a necessary adjunct to the novel. Their primary function is to reconstruct the culture of expectation. Stein had read such reviews for years and knew the attitude that was ostensibly working against her; with these reviews, we can know it too. Moreover,

Ida

came from this news world. In 1937 Stein wrote to her friend William Rogers about her plans for

Ida

: “I want to write a novel about publicity a novel where a person is so publicized that there isn’t any personality left. I want to write about the effect on people of the Hollywood cinema kind of publicity that takes away all identity” (

RM

168). These

Ida

reviews illuminate a similar process of publicization—in this case of a novel. To the extent that collectively these reviews “took away” the complex personality of

Ida

, our discussions will bring it back.

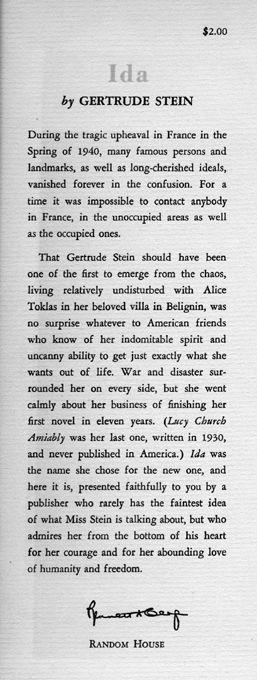

Figure 15: Bennett Cerf’s address to the reader, on the jacket flap of

Ida A Novel

(Random House, 1941).

O. O., “WHAT HAS GERTRUDE STEIN DONE NOW?”

There was a writer erupting named Gertrude Stein. Critics tried to keep Gertrude from being born but when the time came, well, Gertrude came. And as Gertrude came with her also came Alice, so there she was, Stein-Stein.

She always had an Alice B. Toklas. That was Gertrude. Not Ida.

One month was not March and a book came out of Gertrude. She always had to have a book. One month was not March but it was eleven years and Gertrude Stein had not written any novel that is a story of course. This is called a book but it does easily lose itself. So much for Gertrude.

Everybody said well that is just Gertrude Stein not Ida. All of a sudden there was Gertrude Stein again.

What has Gertrude done now?

It is easier for Gertrude Stein to write a book than not a book well why should it be and not be about the Duchess of Windsor.

Little by little it is not.

We said one day.

Is there anything strange in just being Bennett Cerf and publishing Gertrude Stein anyway?

One day in Random House it is not an accident. Yes and no.

It is so easy not to be lucid.

This too happened to Gertrude Stein.

She never was a mother.

Not ever.

Miss Stein not Ida knows that is she does not exactly know some people who are always willing to read her writings.

The wackier the writing the more willing those people are just to read it.

There it is.

Thank Miss Gertrude Stein. Thank Ida. Thank Bennett.

Dear Gertrude.

Yes.

Boston Evening Transcript

(Feb. 15, 1941): sec. 5, p. 1.

CLIFTON FADIMAN, “GETTING GERTIE’S IDA”